Metal of Honor Gallery Guide

In April 1899, in the midst of construction for her new museum, Isabella Stewart Gardner purchased a monumental gold altarpiece by legendary Renaissance artist Simone Martini. The Gardner Museum boasts the largest holding of Simone’s work in this country and his only altarpiece outside Italy. Both the Museum’s paintings, with their intricately worked surfaces, delicately applied highlights, and attention-getting frames, gleam with gold.

Gold is one of the world’s most precious materials. In the medieval Christian tradition, it symbolized heaven and inspired religious metaphors. The heating, melting, and refinement of gold evoked the trials of human souls after death, while its purity and resistance to tarnish recalled the incorruptibility of holy bodies. Gold also invoked specific geographies. By the 1300s, Africa had revolutionized the gold trade with new sources of raw material. Trans-Saharan traders carried gold dust and nuggets north, where artisans transformed them into currency. European gold beaters hammered coins into sheets that painters used as gold leaf. Simone was expert at manipulating the color, sheen, texture, shape, and form of this material. In the process, he expanded gold’s ornamental and symbolic potential to articulate religious messages.

Just as Simone used gold to honor his sacred subjects, contemporary painters Titus Kaphar, Stacy Lynn Waddell, and Kehinde Wiley introduce gold to commemorate and dignify their secular subjects: Black men and women. Drawing on the visual vocabulary and symbolism of gold-ground Christian devotional paintings, these artists approach gold in equally innovative ways, expanding its honorific potential. Their images memorialize identities and adorn Black individuals—often overlooked in Western histories of representation—with the material of eternity and divinity. These three artists, each in their own way, redress histories of erasure through their use of gold. Extending across the Museum’s campus into the Fenway Gallery, where fifteen works from Kaphar’s The Jerome Project, painted mostly in 2014-2015, are on view, and onto the Anne H. Fitzpatrick Façade with Waddell’s Home House, 2022, the connections among these works invite us to consider how artists innovate in the present by building on accomplishments of the distant past.

SIMONE MARTINI

Simone Martini (Siena, about 1284 - 1344) transformed painting with his conceptual originality, novel compositions, and masterful manipulation of gold. Born in Siena, he became the city’s painter, executing a massive, celebrated image of civic virtue, called the Maestà, in the town hall. His career took him across the Italian peninsula, as painter to popes, kings, and scions of Renaissance dynasties.

At the same time, he pioneered new innovations in altarpiece construction, design, and imagery, creating polyptychs—multi-panel altarpieces—for churches in the cities of San Gimignano, Pisa, and Orvieto. Both Gardner Museum paintings come from Orvieto, a small city north of Rome that served as the pope’s summer retreat. Simone produced three altarpieces for the city’s most important religious orders and worked for Orvieto’s leading family, the Monaldeschi. A woman in that family likely commissioned, or had commissioned for her, the small devotional painting that you see below.

Papal contacts finally brought Simone to Avignon, France. There he befriended the legendary poet Petrarch, who had him paint a beautiful frontispiece in his favorite book as a token of their friendship. Simone died in Avignon in 1344 but his reputation lived on, above all in Italy, where he was esteemed by generations of painters who adopted many of his novel compositions and innovative techniques.

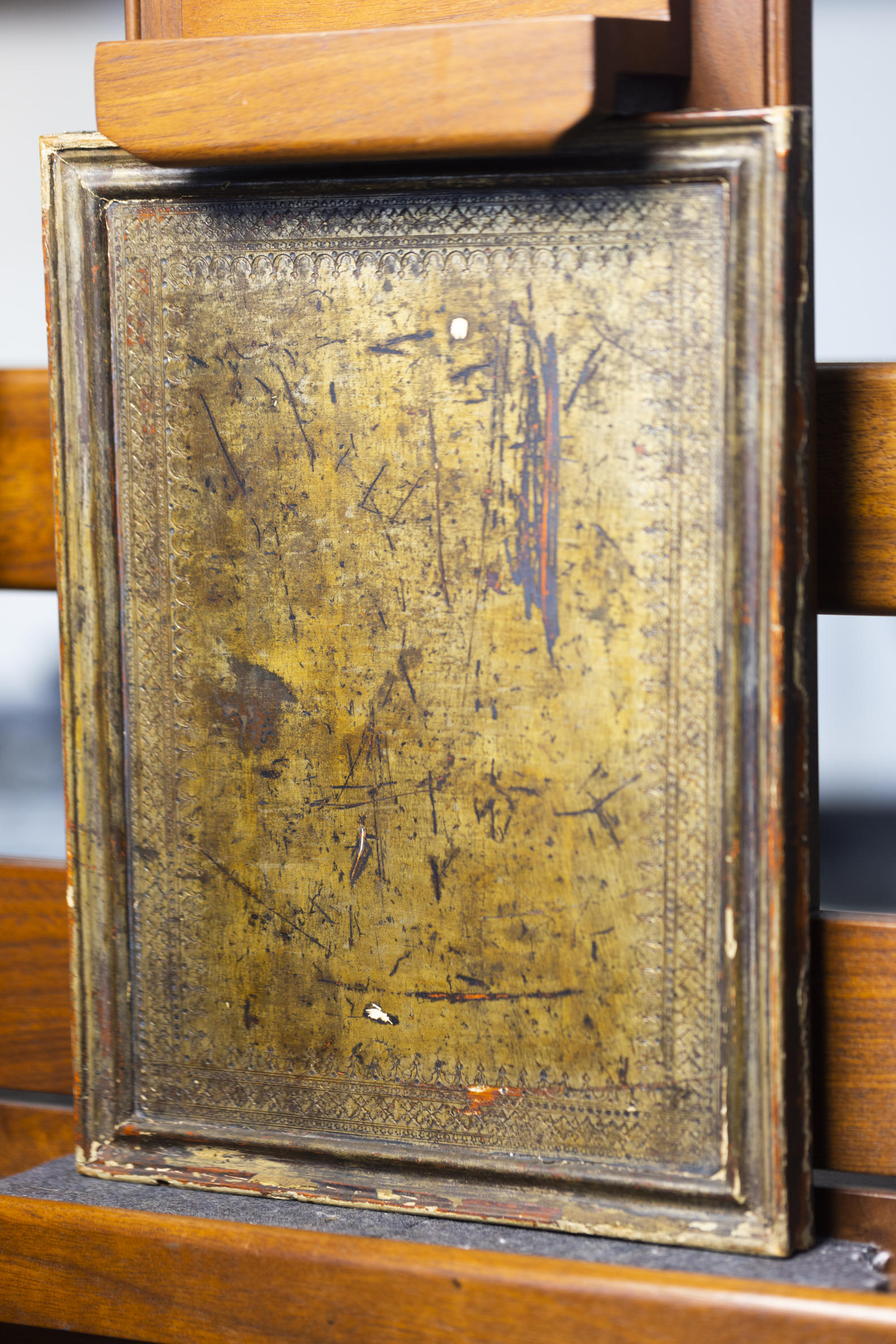

GOLDWORK

Simone Martini’s technical accomplishments reveal his mastery of the metal’s full potential. In Simone’s workshop, gold came first, applied to the support before painting began. But gold is more than just a backdrop to Simone’s painting. It also represents objects—like crowns, swords, and fabrics—and simulates their visual effects, evoking the glitter, sparkle, and shine of luxury items appropriate to the kingdom of Heaven. Punched, tooled, and applied gold ornament honors sacred figures, distinguishes the hierarchy between Christ and his disciples, and signals ranks amongst the saints. Simone’s gilded frames separate these holy figures’ space from ours and set up dynamic encounters with divinity. By deliberately rupturing the gold border with painted forms, he signals the painting surface as a site of illusion, transforming the devotional image into an imminent event and crafting a sacred encounter that is both close at hand and reverentially distant.

THE POLYPTYCH

Simone Martini (Siena, about 1284 – 1344), Virgin and Child with Saints, about 1320. Gold and tempera on panel, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.

Towering over the altar of the church of Santa Maria dei Servi, this polyptych—an altarpiece with multiple panels—reaches for heaven. In this work, Simone Martini pushed the possibilities of gold to new heights, expanding the size of each gilded surface to better capture the congregation’s attention while finding new ways to articulate the identities of the devotees. He filled the five pinnacles (top spaces) with a figure of Christ with his hand raised in judgment flanked by angels holding instruments of his Passion—like the column on which he was beaten—and trumpets of the Last Judgment. Together they reflect the devotional preoccupations of the Servites, or Servants of Mary, for whom the Virgin Mary’s sorrow over her son’s suffering was a particular concern. Their altarpiece may have been paid for by a woman whose own interests are reflected in the two female saints who flank the Virgin Mary and Child.

Simone’s painting reveals the full range of his innovative techniques in both gold and silver. For Saints Lucy and Catherine, he evokes bejeweled broaches and adorns their cloaks with finely patterned mordant-gilded decorations simulating fine damask fabrics. Silver, now tarnished, lent its sparkle to both Paul’s sword and the spandrels’ (rounded corners) evil dragons damned by Christ.

Object Description

This altarpiece by Simone Martini is made up of five separate vertical panels, each with a triangular pinnacle above. The center features the Virgin and Child with four saints on the panels and pinnacles. The frames on the panels have straight sides that curve in to meet at the top, and are flat at the bottom. With the exception of the figures, the panels and pinnacles are primarily gold. In the center panel, which is larger than the others, is the light-skinned Virgin Mary and the baby Jesus. Mary is wearing a red gown and blue hooded robe. Her head is tilted to our right and her eyes look slightly upward. She holds three white flowers in her right hand. The baby Jesus looks up at his mother and touches her face with his right hand. He wears a pink shirt and is partially wrapped in a red drape.

Below the figure, a black rectangle with gold writing reads "AUA. MARIA. GRATIA. PLENA." The pinnacle above the pair contains a light-skinned Christ partially wrapped in a red robe, displaying wounds on his body and hands. In the panel to our far left is a medium-light-skinned Saint Paul. He is balding with a long, thick, dark beard, and is dressed in lavender, turquoise, and red robes. His faces our right, and he carries a sword in his right hand and a book in his left. Below the figure, a blue rectangle with gold writing reads "SCS. PAULUS. AP". In the pinnacle above is a light-skinned angel in pink with blue wings. The next image to the right of Saint Paul is a light-skinned Saint Lucy. She is dressed in a red gown with a turquoise and gold robe, and a white scarf drapes over her head and shoulders. She holds a small jug or lamp in her right hand. Below the figure, a blue rectangle with gold writing reads "SCA. LUCIA. V. ET. M." The angel in the pinnacle above wears turquoise and green and has pink wings. The figure to the right of the Virgin and Child is a light-skinned Saint Catherine. She is wearing a red robe with a white collar and lining and a gold and jeweled crown on her head. She is facing forward with an unfocused gaze, and holds a palm in her right hand and a book in her left. Below the figure, a blue rectangle with gold writing reads "SCA. CATHARINA. ET. M." The angel in the pinnacle above appears to be holding a palm and cross. The image in the panel to your far right is a medium-light-skinned Saint John the Baptist. He is wearing a red robe over a brown garment tied at the waist. He is pointing the index finger of his right hand and holds the cross with his left. Below the figure, a blue rectangle with gold writing reads "SCS. JOANNES. BAPTA." The angel in the pinnacle above wears a pink drape over a blue robe and appears to be blowing a horn.

Credit: Photo by Bearwalk Cinema

FILM

In preparation for this exhibition, Gardner staff spent time with Artist-in-Residence Stacy Lynn Waddell. Together they took a closer look at Simone Martini’s painting in the Museum’s collection and Stacy described how his innovative use of gold inspires her. Please note: Gardner Museum conservators advised the film participants on safe handling of the artworks.

Metal of Honor, Film with sound, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2022. About 4 minutes

Learn More About Gold

CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS

Metal of Honor: Gold from Simone Martini to Contemporary Art is supported by the Abrams Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Wagner Foundation, the Robert Lehman Foundation, Fredericka and Howard Stevenson, and the Samuel H. Kress Foundation.

Additional support is provided by an endowment grant from the Mellon Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Media Partner: The Boston Globe

The Museum receives operating support from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, which is supported by the state of Massachusetts and the National Endowment for the Arts.