Fenway Court, as the museum was known during Isabella Stewart Gardner’s lifetime, first opened its doors to the broader public on February 23, 1903. The museum had made its debut just two months prior, on New Year’s Day, with an invitation-only gathering of several hundred of Gardner’s friends. Treated to a night-time concert followed by a candlelight tour and supper in the Dutch Room, her guests left stunned and in awe.

Photography by David Pérez Pictures

Courtyard at night, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, 2024

Public anticipation was therefore high, especially as the “palace” had been shrouded in mystery during its construction. Admission was limited to 200 people who were required to buy tickets in advance at one dollar a piece (a hefty sum at the time). The visit was tightly scripted; visitors were required to move in one direction, guards kept people moving under a watchful eye and note-taking was forbidden. Nevertheless, Fenway Court did not disappoint. As one report noted, the “bright imaginings” of the fortunate few scarcely “prepared them for the reality.” The spectacle they witnessed “was beyond all possible expectation.”

But if the public opening left visitors awe-struck, for Mrs. Gardner—who lived in an apartment on the fourth floor of the building—it had the opposite effect. As she wrote to her legal advisor and confidant, Henry Swift: “The experiment of exhibiting to the public this spring has proved to me that it is absolutely impossible for me to live such a life as the present exhibition entails.” While Gardner always planned to open Fenway Court as a public museum following her death, she was reluctant to admit the public during her lifetime and was motivated to do so chiefly to avoid paying import tariffs on the art and taxes on the building.

Incorporation sheltered the museum from property taxes, but more importantly, it also allowed Gardner to avoid the Dingley Tariff. From 1897 through 1909, the trade law imposed punishing duties on a wide variety of imported goods, including fine art, domestic furnishings, and building materials—everything that she needed to build the museum that was then taking shape in her mind. To give one example, in 1896 she pressed her agent, Bernard Berenson, to move quickly on the purchase of Titian’s Rape of Europa ahead of the new law’s passage.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P26e1). See it in the Titian Room.

Titian (Italian, 1488–1576), The Rape of Europa, 1562. Oil on canvas, 178 x 205 cm (70 1/16 x 80 11/16 in.)

Had the tariff been in effect when she bought Europa, the sale price of $100,000 would have carried a surplus duty of $20,000 ($3,850,000 and $771,000 today, respectively). The tax rate on imported stone, textiles, ceramics, etc. was even higher. Once the tariff went into effect, she stored everything she bought in Paris, awaiting a change in policy. Incorporating her fledging museum offered a seemingly painless way forward, because under the law registered charitable institutions were exempt from tariffs. Soon after she signed the legal papers, shipments of art and sundry materials began flowing freely from France to the Fenway, and building could commence.

But after the first public days she came to regret her pact with the government. The sight of strangers parading through her carefully curated rooms—touching things as they went—proved unbearable. An early biographer claims Gardner once came across a visitor, scissors in hand, poised to cut a swatch of a tapestry as a souvenir!

Photo: Sean Dungan

Tapestry Room, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Gardner abruptly cancelled further admissions in March 1903, saying she could no longer honor her commitment to open her new museum to the public. Henry Swift was chagrined: “Have you decided to abandon your noble purpose? I shall be deeply grieved and very much ashamed if this is so.” The press grew suspicious that Gardner had intended from the first to use the brief public opening as a loophole to avoid paying the government, and then promptly keep the collection to herself. One paper remarked sarcastically that she had “solved the problem of importing an art collection from Europe for private use without paying a cent for it…. This is the secret: Say you are going to found a public museum…. Throw the building, or at least part of it, open to that part of the public who have purchased tickets. Rush them through like so many express trains…. Rush them out at the sound of a gong…. Repeat this ten or a dozen times. And there you are. Now I ask you if this is right?”

By the fall of 1903, with no scheduled public openings on the calendar, Washington got involved. An ultimatum soon followed. Either Fenway Court would open to the public on a regular basis, or the “museum incorporated” would be dissolved and Gardner would be liable for unpaid tariffs amounting to $194,000 ($7,160,000 today). After much deliberation, Gardner proposed a compromise. She would pay what she owed, but then be free to run her museum as she saw fit. Fenway Court would open twice a year for two weeks, around Easter and Thanksgiving, to two hundred fee-paying guests a day. That was good enough to stave off Boston property taxes, but not for the feds, who decreed such limited access fell short of qualifying as a public institution. Her decision would cost her dearly.

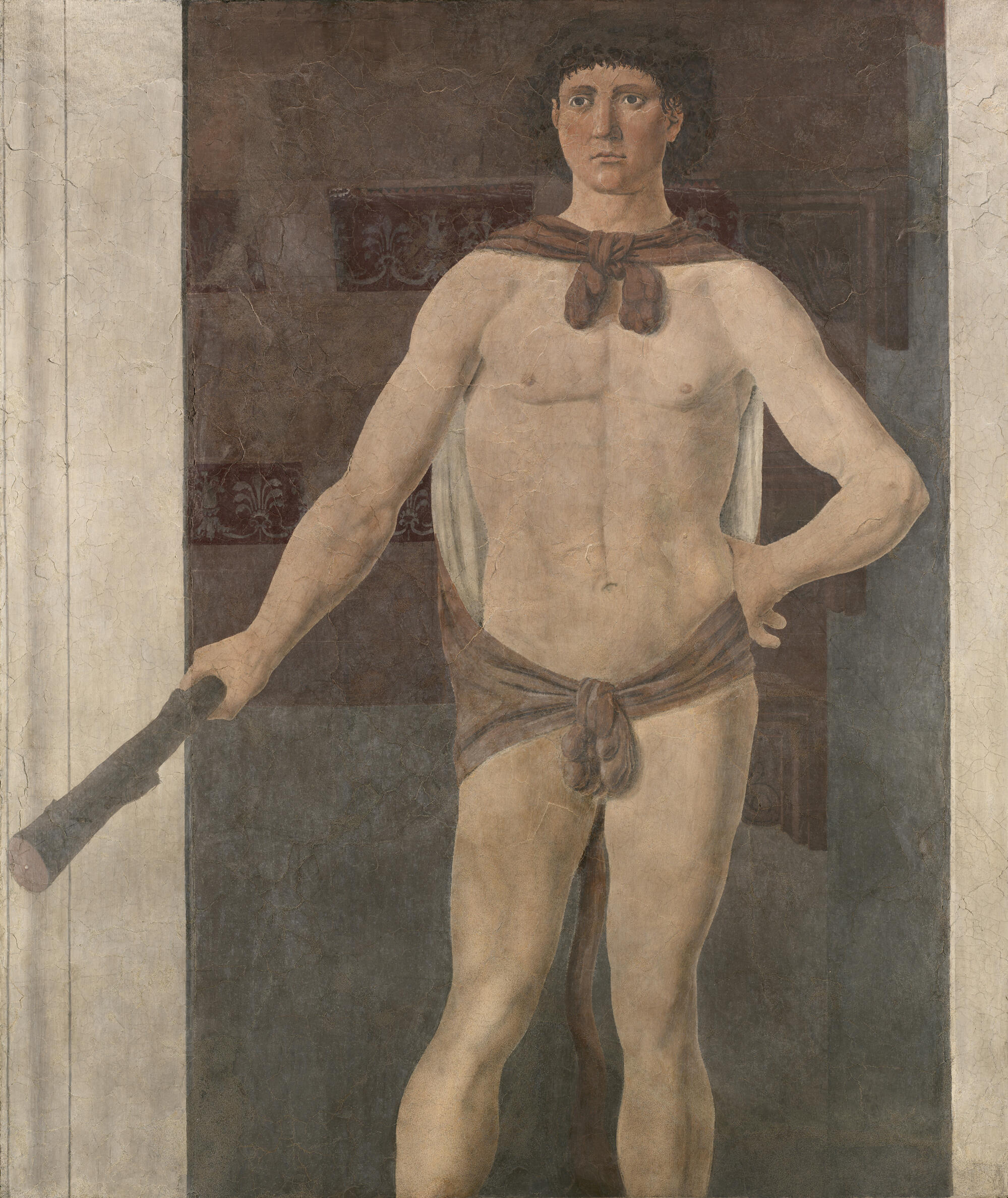

Gardner continued acquiring works of art after 1903, but with the tariff still in place, she again kept new acquisitions in Paris waiting for the law to be changed. She fell afoul of the law once more in 1908 when an acquaintance, Emily Chadbourne, imported undeclared tapestries and Piero della Francesca’s Hercules into the United States.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P15e17)

Piero della Francesca (Italian, about 1415–1492), Hercules, about 1470. Tempera on plaster, 151 x 126 cm (59 7/16 x 49 5/8 in.)

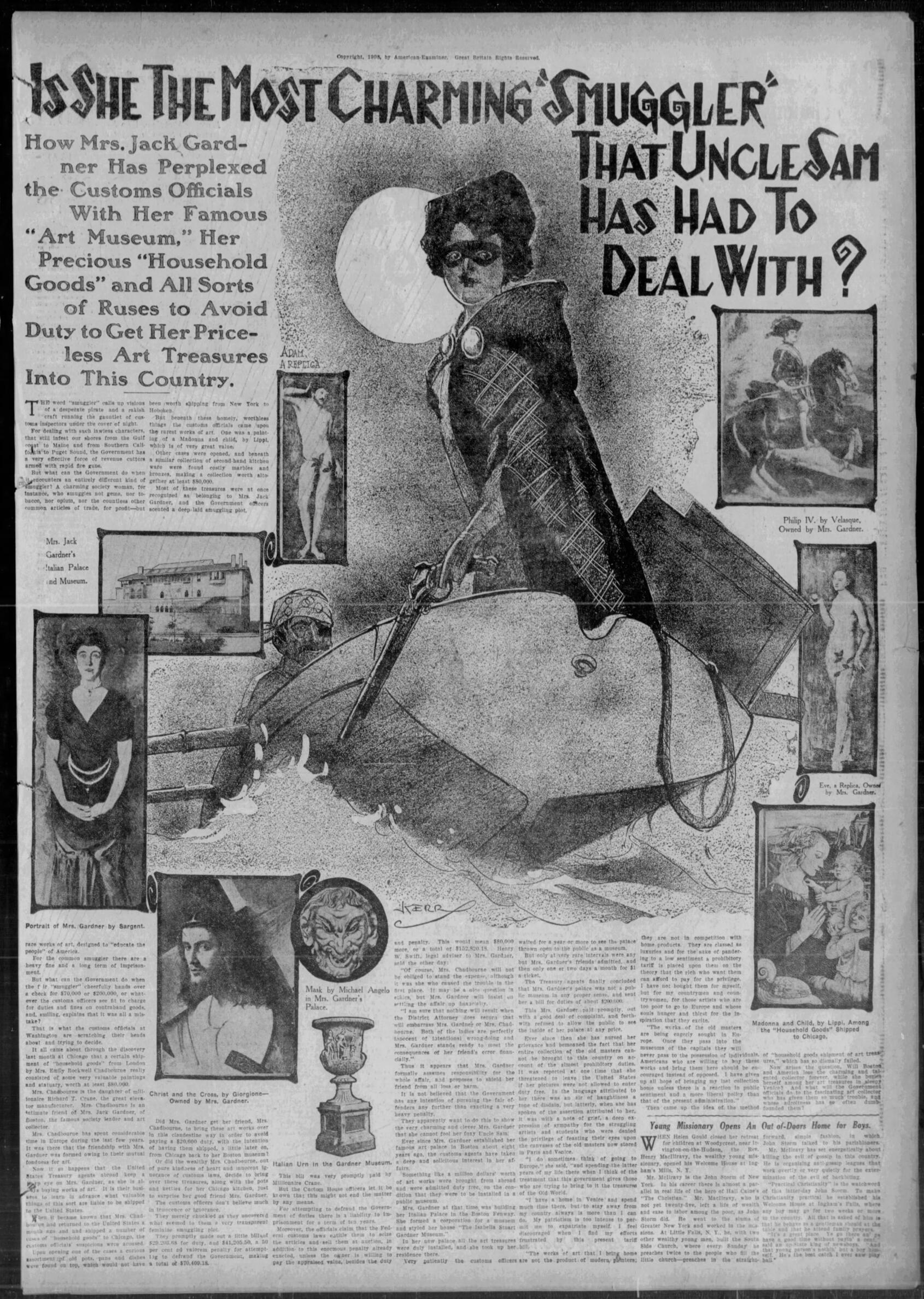

The artworks belonged to Gardner, and had been in Chadbourne’s care in Europe. Caught by customs officials, Chadbourne claimed it was all an innocent misunderstanding of which Gardner had no knowledge. The press, however, claimed it was all a ruse and likened Gardner to a Highland bandit of yore. Isabella may have appreciated the nod to her Scottish heritage, but not the heavy penalty that fell upon her head—unpaid duty of $80,000 for the undeclared items plus a fine of $70,000, for a total of $150,000 (over $5,000,000 today).

Courtesy of San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

“Is She The Most Charming ‘Smuggler’ That Uncle Sam Has Had To Deal With?” San Francisco Examiner, 20 September 1908, p. 61

The Dingley Act was finally repealed in 1909, but it was too late to help Mrs. Gardner. In the end, tariffs had cost her over $12 million in today’s dollars. No American collector of the Gilded Age suffered a greater financial loss under the tariff law. Even the once hostile press turned sympathetic, wondering how much greater her collection would have been had she been free to spend her money on works of art instead of import duties. Though nothing could compensate for the art and money lost, close friends came together to acknowledge what she had achieved with the creation of her museum, presenting her with a beautifully bound and signed book of tribute, whose dedication read: “You have conceived and built a beautiful house and filled it with treasures of art. To this end, you have worked with untiring energy and love of your task, a task involving ungrudging self-denial. For us and for posterity, you have created a museum priceless for refreshment and education, a unique achievement of imagination, skill and ardent purpose. For this great public benefaction, we offer you our deepest gratitude.”

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (U19w40). See it in the Tapestry Room.

Mary Crease Sears (American, 1880–1938, binder), Agnes St. John (American, 1890–1929, binder) and John Templeman Coolidge (American, 1856–1945, designer), Tribute Book of Autographs, 1909. Binding: leather set with silver and an emerald; ink on paper, 23 x 15 cm (9 1/16 x 5 7/8 in.)

Perhaps Mrs. Gardner would take comfort in knowing that, a century after her death, her costly entanglement with tariffs and taxes had become the stuff of history while her museum, dedicated to “the education and enjoyment of the public forever,” continues to inspire wonder in those who visit.

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

Visiting Fenway Court in the Days of Isabella

Read More on the Blog

A Grand Opening

Read More on the Blog

The End Justifies the Means