Mary Dexter wrote, “I am nearly mad with joy!” to her mother on September 10, 1914. The 28-year-old Bedford, Massachusetts woman had just been offered a post at the American War Hospital in Devonshire, England. This opportunity set Mary Dexter up for a career of care during World War I.

The Dexter women were friends of Isabella Stewart Gardner—Mary’s mother Emily Dexter sent Isabella updates about the war effort in London in numerous letters. Isabella owned an annotated manuscript for “In the Soldier’s Service,” Mary Dexter’s collected letters to her mother, as well as a published copy of the memoir. It is likely that the manuscript was a gift to Isabella Stewart Gardner from Emily Dexter, who also edited the memoir.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.006545). Isabella kept this manuscript in the Macknight Room with other World War I related ephemera.

Mary Dexter (American, born 1886), ‘In the Soldier’s Service,” page 1, 1914

Mary Dexter started her work on “In the Soldiers’ Service” after fighting broke out on the Western Front in the fall of 1914. At the American War Hospital in Paignton, she was given the role of a probationer, or “pro” as she cheerfully called herself. Mary was extremely proud of her contribution to the war effort, stating that:

Being in a Red Cross military hospital is next best to going to the front.

In Mary’s role as a “pro,” she carried out duties similar to a modern-day nutritionist, ensuring that the soldiers in her care (numbering fifty-four at the beginning of her service) had their dietary needs met. She fulfilled requests for special diets and provided pre-chopped meals for patients with arm injuries or minced meat for a patient with a bullet wound in his jaw. Once more wounded soldiers were brought to the hospital, Mary moved full-time to surgery where she spent her time assisting in wound dressing and bone setting. Here, Mary flourished.

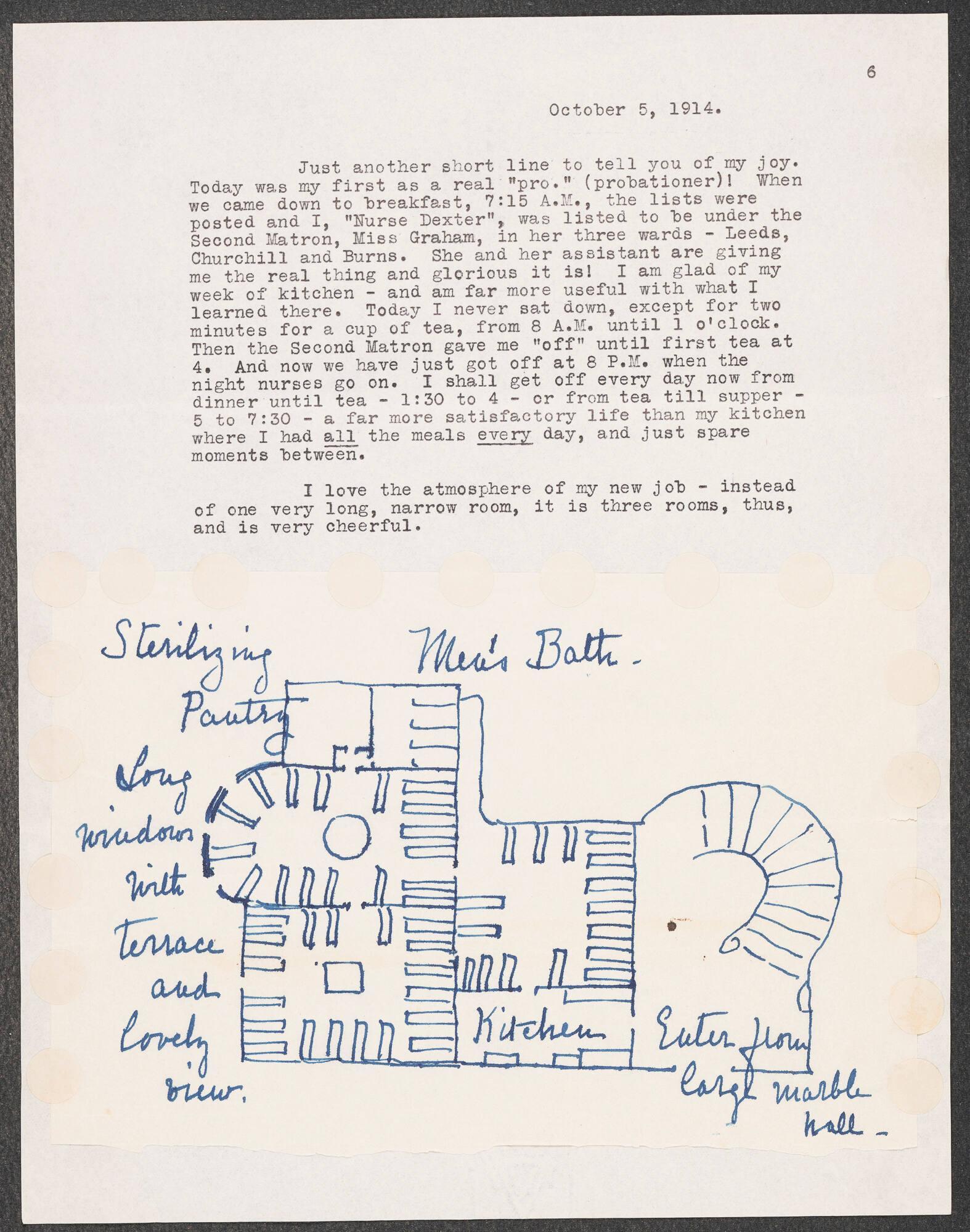

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.006545)

Mary Dexter (American, born 1886), Plan of the American War Hospital, Paignton, 1914 in the manuscript for “In the Soldiers’ Service”

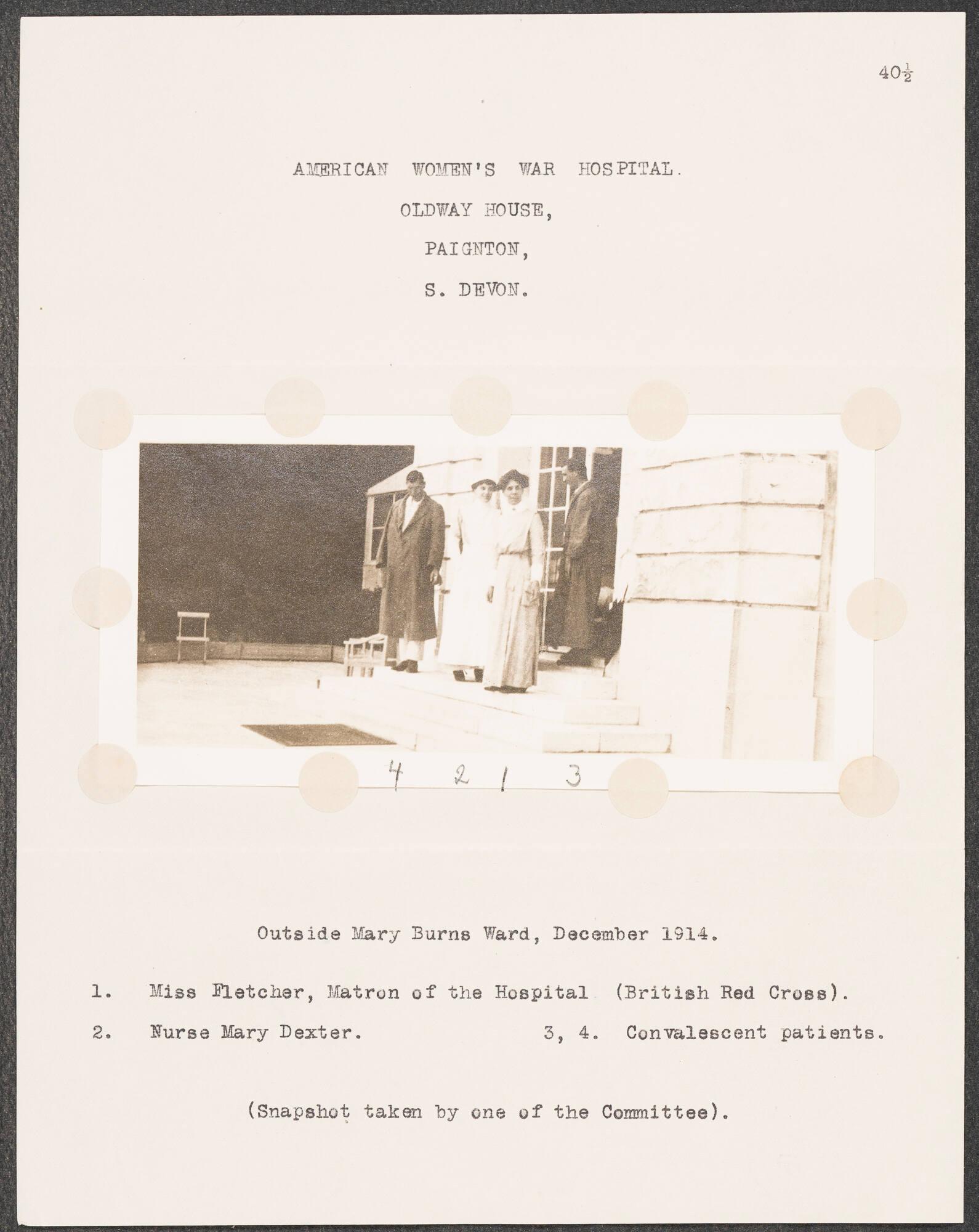

Mary Dexter cared deeply about the men whom she nursed. While she did not mention their names in her letters (likely a wartime security measure as much as it was to protect their personal privacy), Mary wrote about them with great empathy and affection. For Christmas 1914, she even made sure that the soldiers were gifted stockings filled with fruit, jam, tobacco, and other gifts.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.006545)

Mary Dexter (American, born 1886), “Outside Mary Burns Ward, December 1914”

Mary spent less than a year at the war hospital in England. In June 1915, she took another job on the Western Front in Belgium. Here, she once again worked in surgery which was constantly busy with patients as the war raged on outside the hospital. Mary wrote that she could hear and see shelling from her ward. Though extremely busy, Mary Dexter’s time in this Belgian hospital was short—in August 1915, a little over a month after taking on this new position, she was recalled to London after contracting scarlet fever.

After recuperating from her own illness, Mary continued her mission of care. During her time in war hospitals, she had interacted with many patients with shell-shock, a condition that is now known to be a type of post-traumatic stress disorder. Mary took courses on shell-shock and applied psychology at the Medico-Psychological Clinic in London. She also was a psychologist’s patient herself—“every student [had] to be analyzed” in order to pass the course. She compared psychoanalysis to her work in the hospitals, calling it a kind of “mental surgery,” and soon started taking on patients of her own.

During a break in her coursework and a lull in shell-shock patients in late 1917, Mary accepted a position as an ambulance driver on the Western Front in France. This ambulance unit, the Hackett-Lowther Unit, was the first all-female unit to serve with the French army. Mary drove wounded soldiers from the trenches to the hospitals in northern France until a back injury sent her back to London and ended her four years of military service.

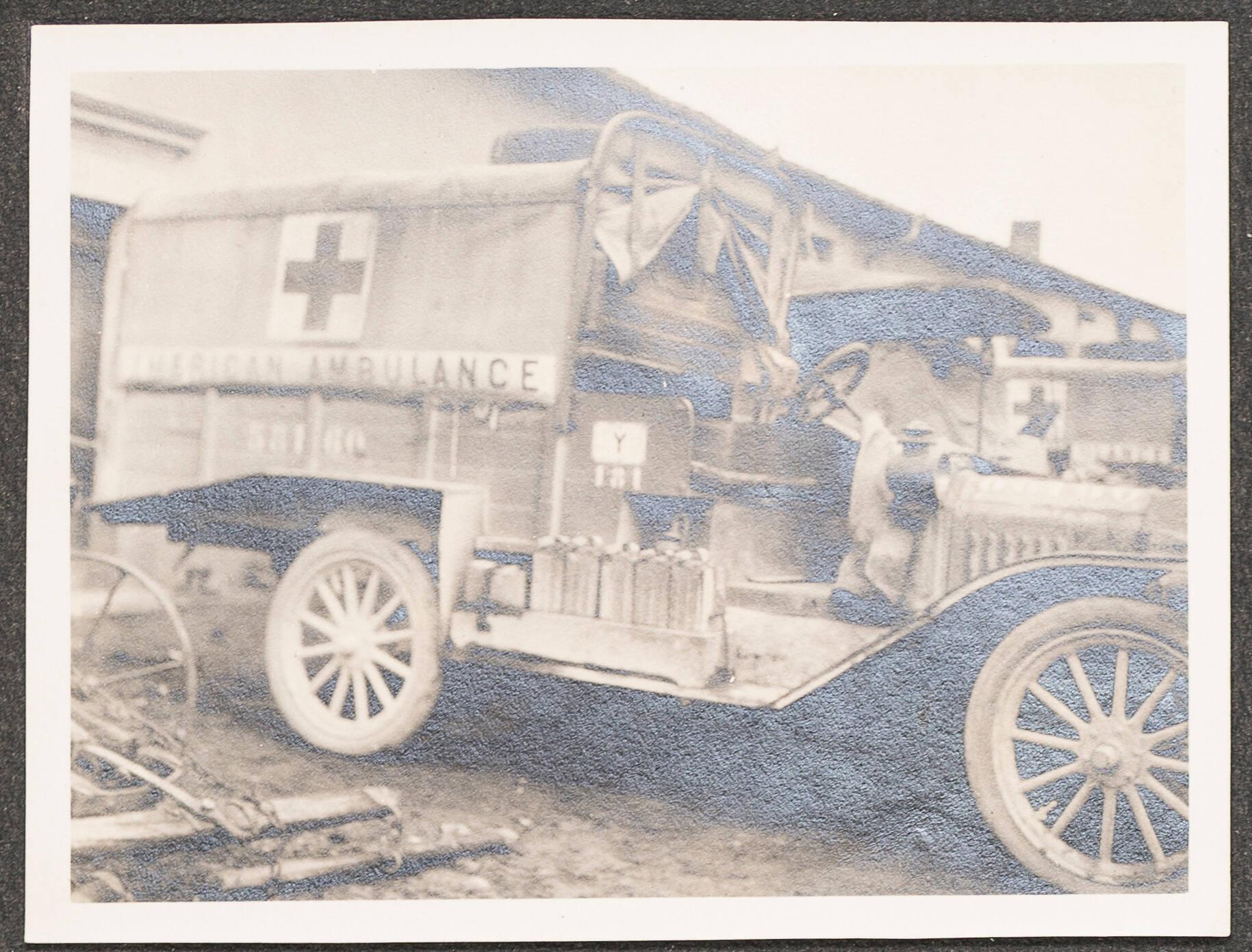

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.007478). Isabella displayed this photograph in the Prichard Case in the Blue Room.

Although she did not have the same on-the-ground commitment as Mary Dexter, Isabella Stewart Gardner also contributed to the war effort, specifically to the healing of wounded soldiers. Her friend A. Piatt Andrew went to the front in France as an American volunteer and co-founded the charitable organization known as the American Field Service. Like the Hackett-Lowther Unit, this was an ambulance service that shuttled soldiers to medical care. Isabella contributed financially to the American Field Service, financially sponsoring an ambulance which was marked in tribute with a “Y” for her nickname “Ysabella.”

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.007478). Isabella displayed this photograph in the Prichard Case in the Blue Room.

Isabella kept her memorabilia related to both Mary Dexter and A. Piatt Andrew’s wartime service, as well as other letters and ephemera from World War I, in the Macknight Room, an intimate, small room on the first floor of the museum previously used as her personal study. The Macknight Room is chock-full of small items that held great sentimental value to Isabella, and her inclusion of an annotated manuscript of Mary Dexter’s book illustrates the great respect that Isabella must have held for this wartime healer.

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

Isabella and the American Field Service During World War I

Read More on the Blog

Anna Coleman Ladd: Art Helping Veterans

Read More on the Blog

Anna Hyatt Huntington: World War I Memorial to the Sons of Gloucester