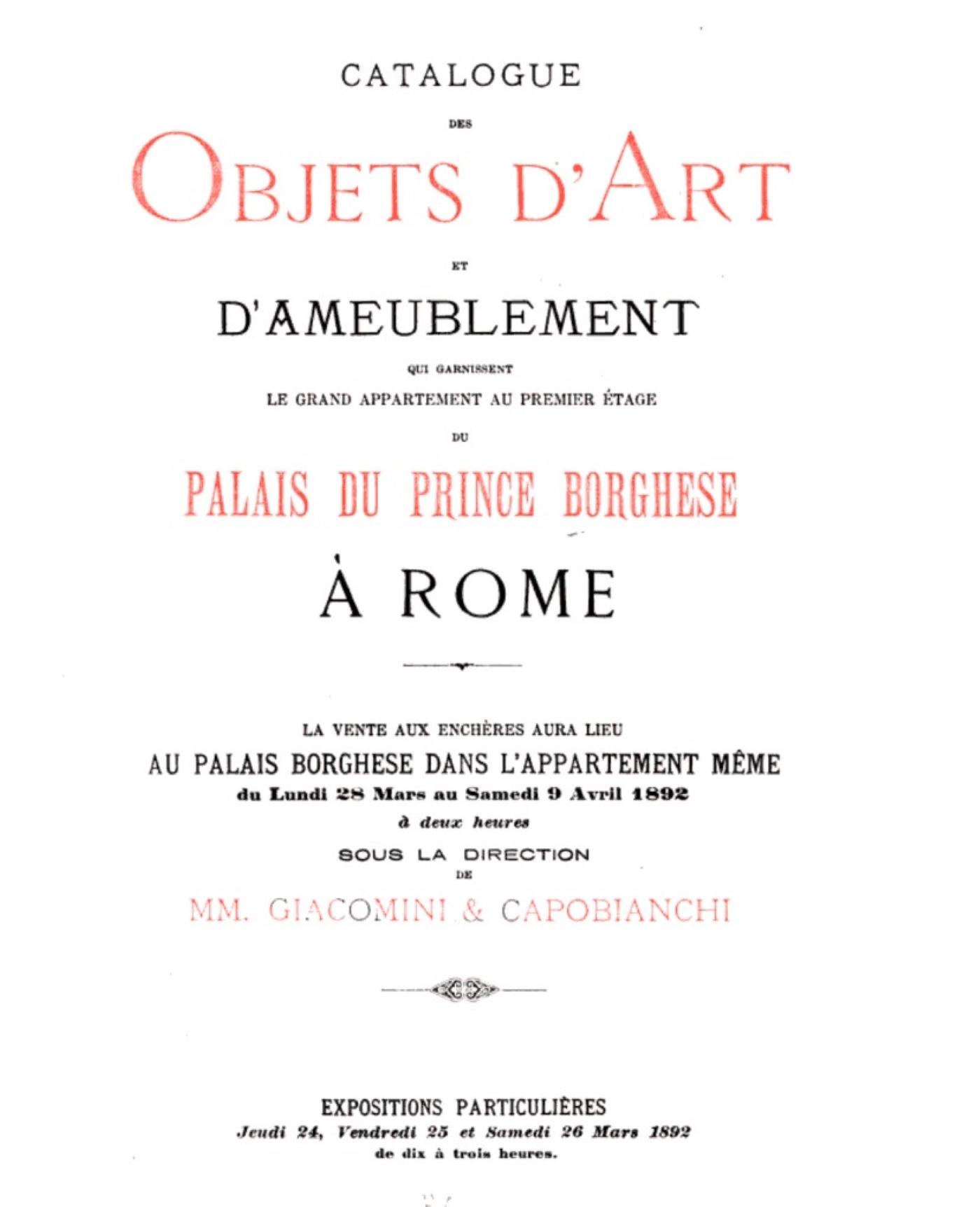

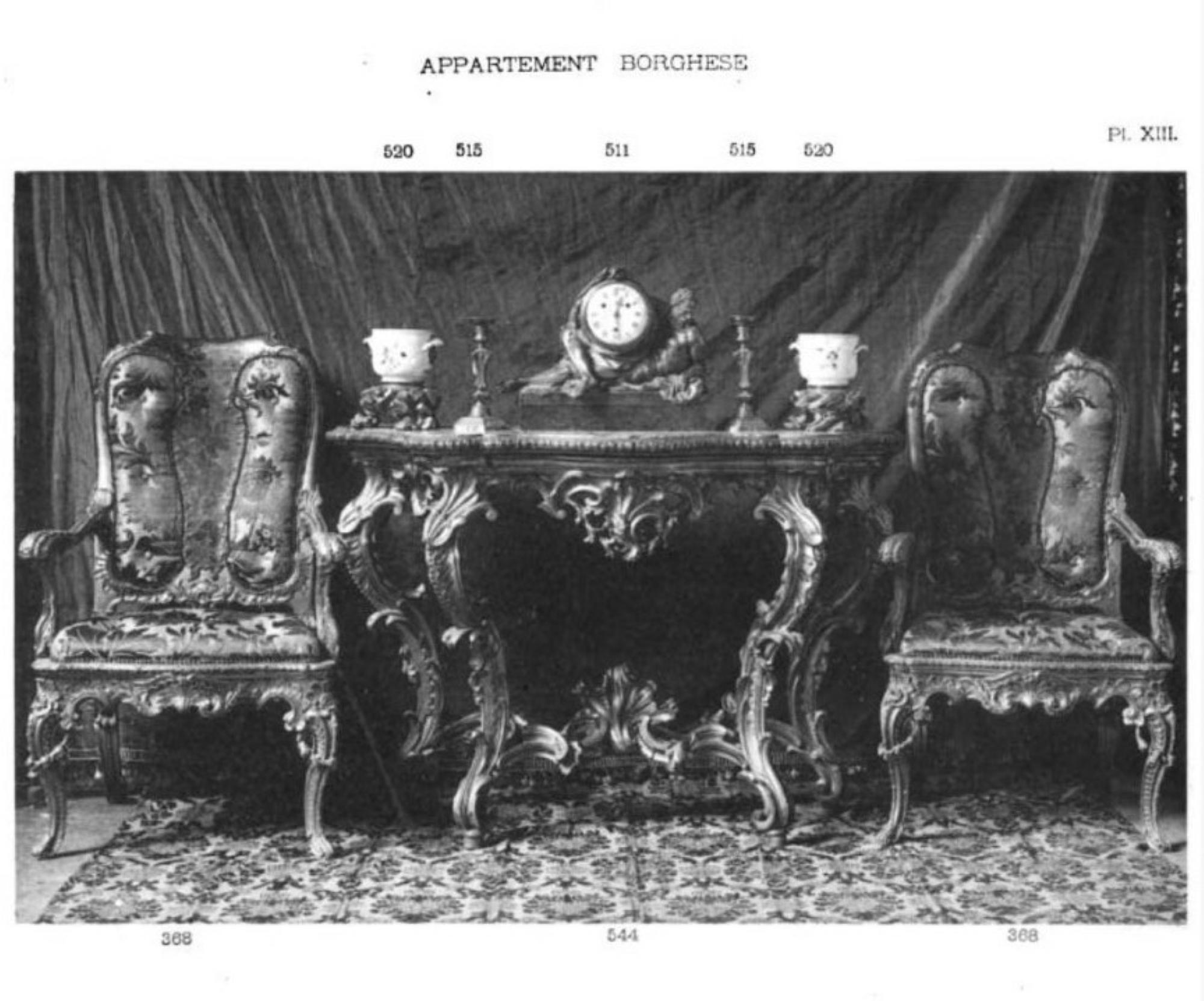

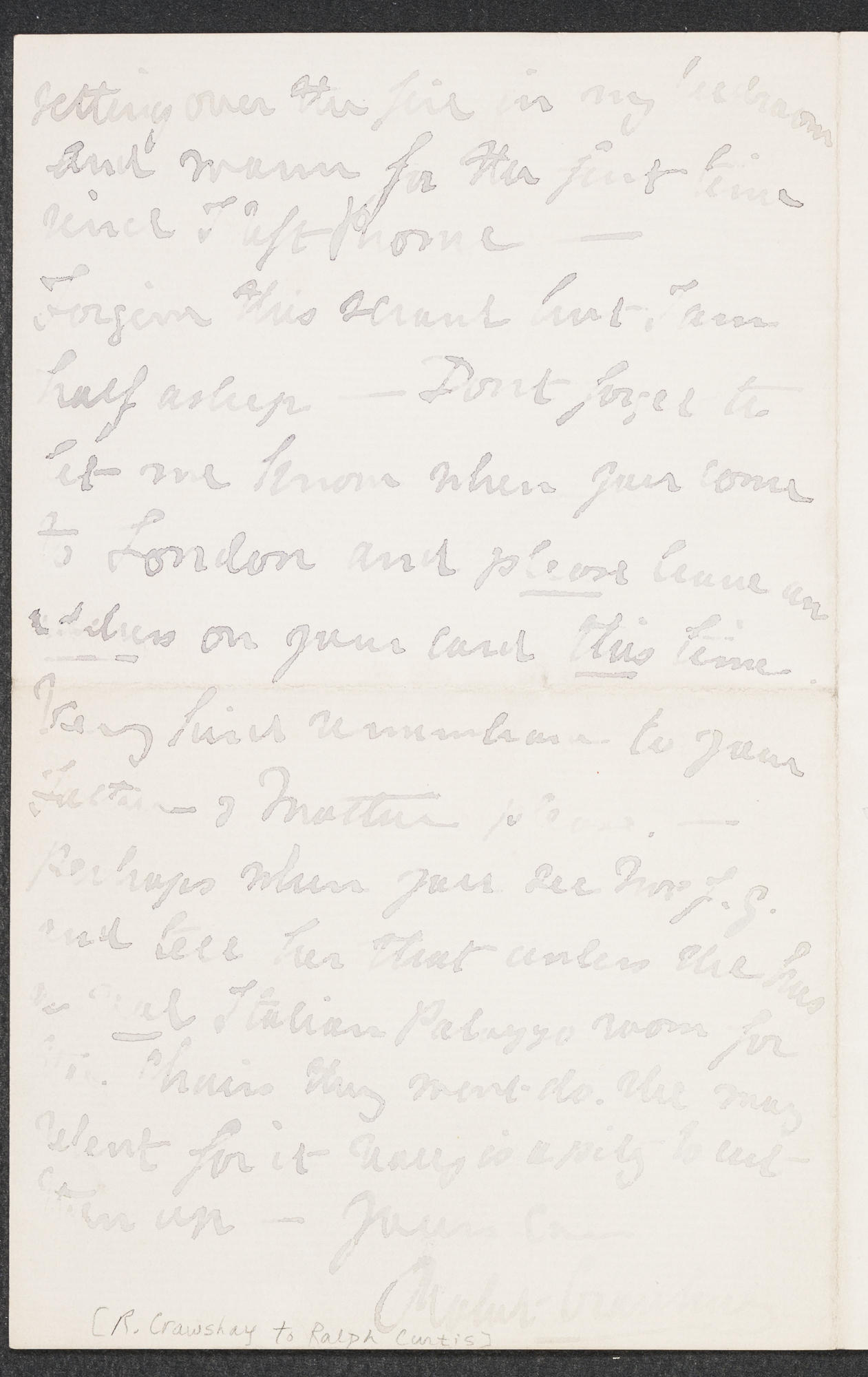

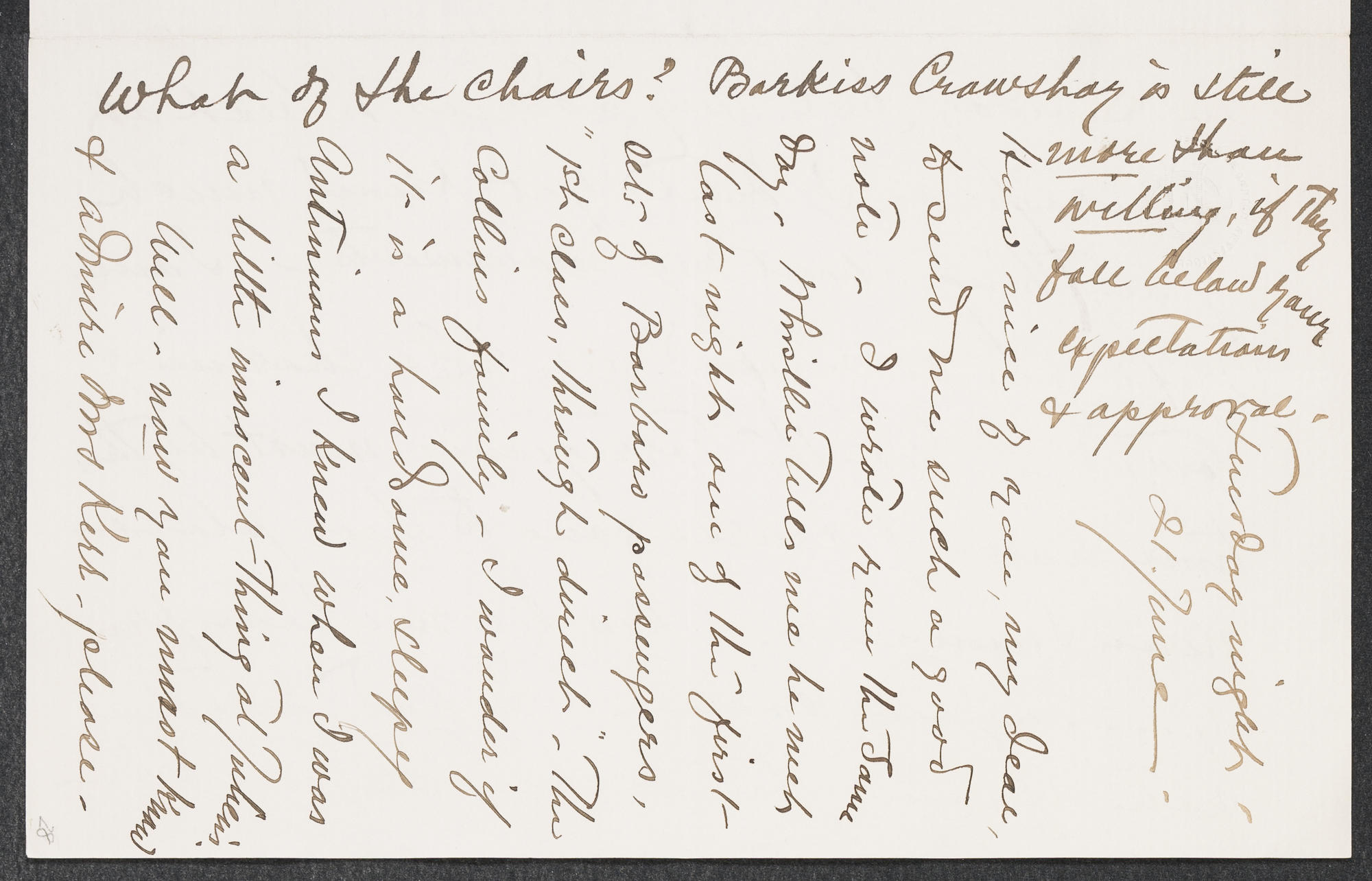

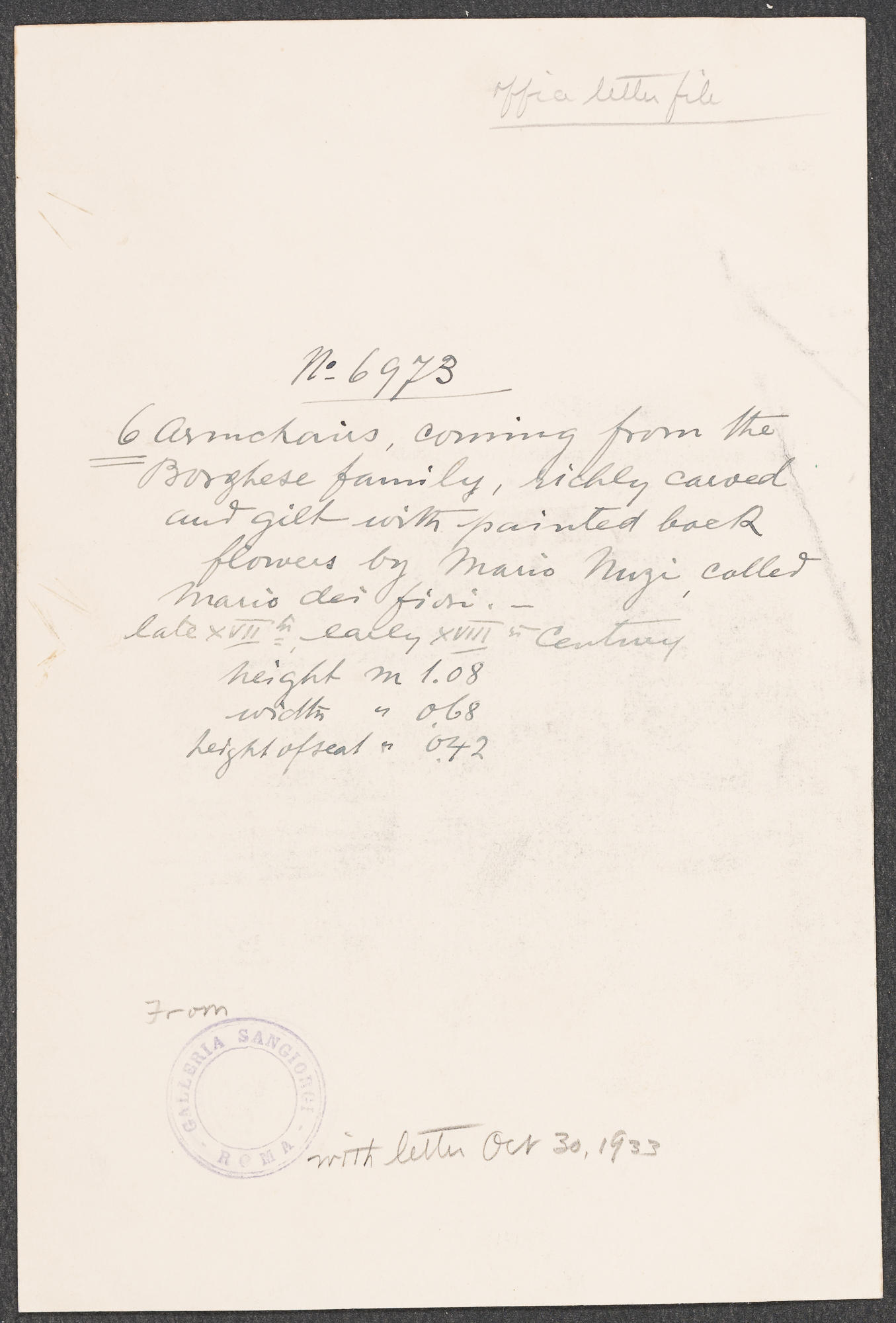

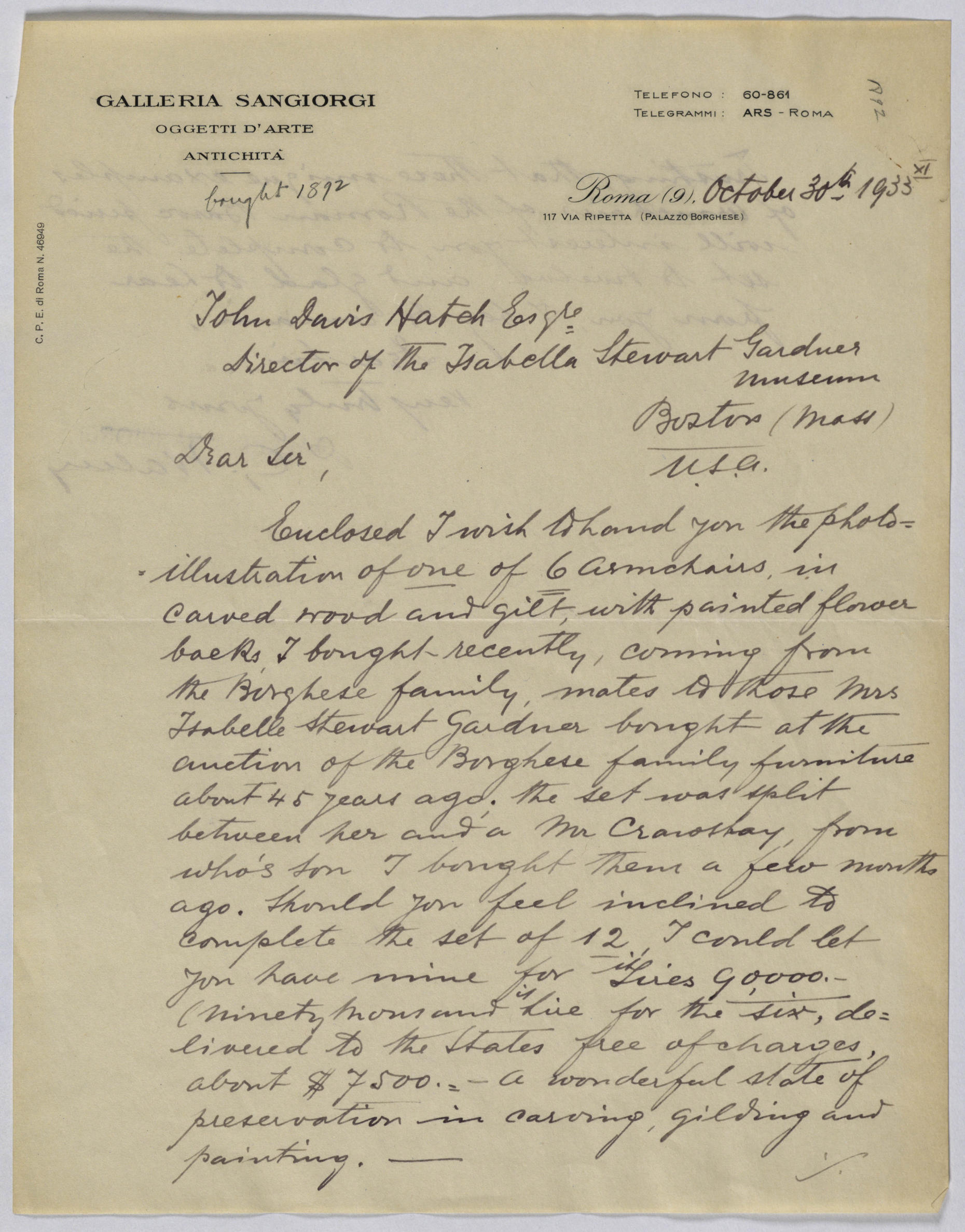

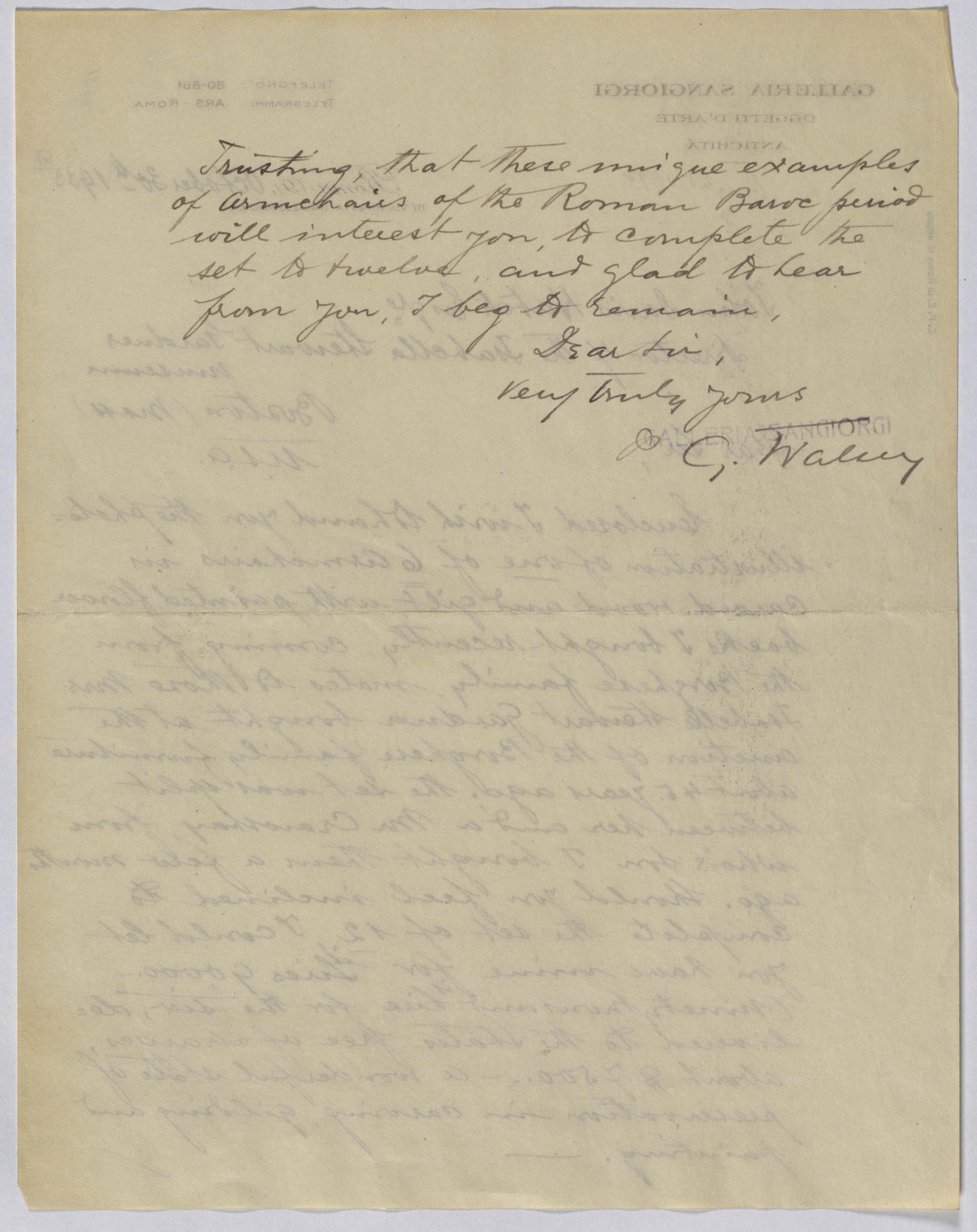

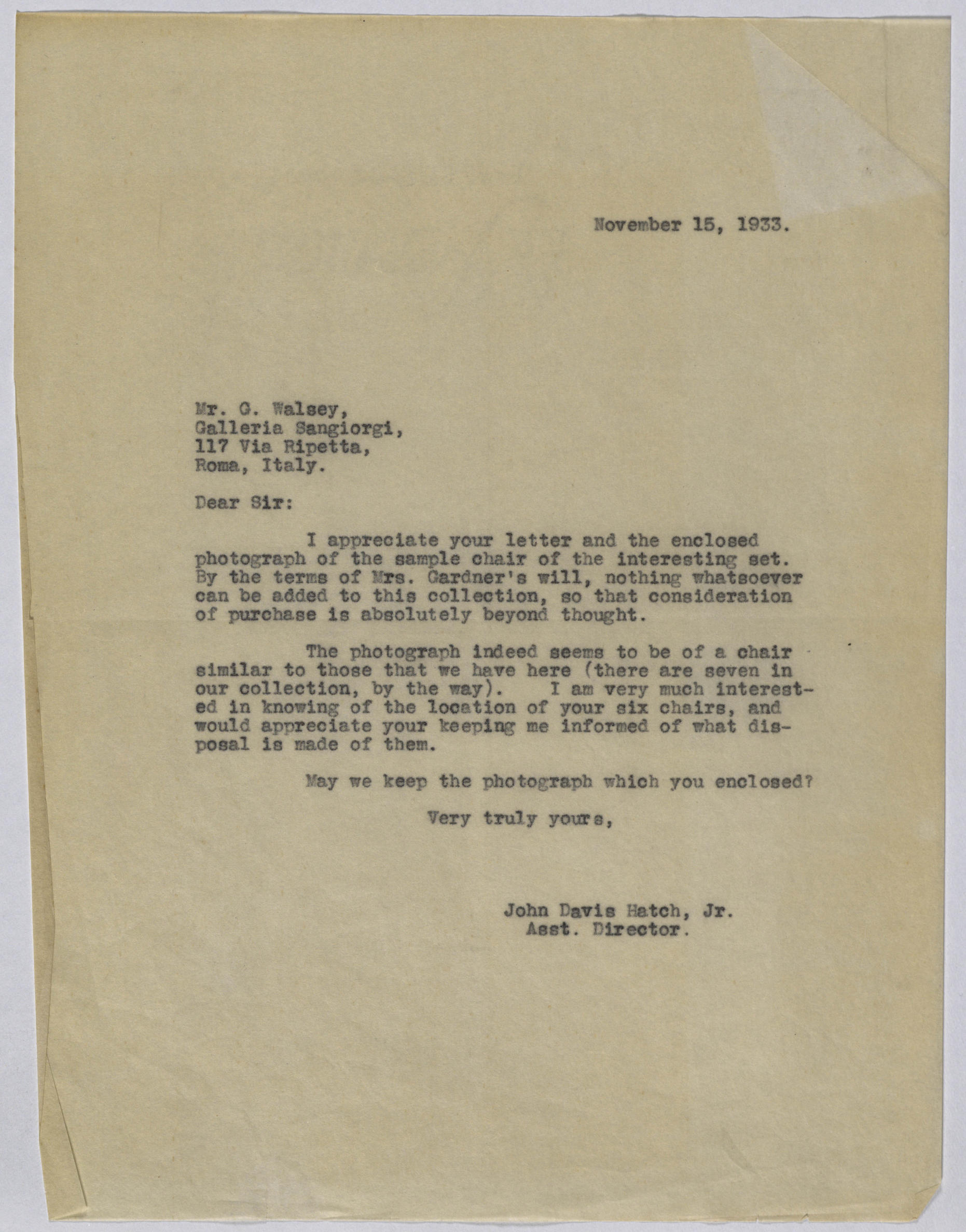

On 2 April 1982, Robert Thompson Crawshay (1853–1944), whose father and namesake was a British ironmaster, purchased the first six chairs (lots 368–370). The remaining seven chairs (lots 371–373) were purchased by the American painter and art collector Ralph Wormley Curtis (1854–1922), on the behalf of Isabella, for 7350 francs.

Prior to making their trip across the Atlantic, the Borghese armchairs were sent to Venice, where Antonio Carrer (active 1877–1912), art dealer and restorer, inspected and treated the chairs, removing the aging upholstery. Arriving in Boston a number of years in advance of the Museum’s completion, the chairs were arranged by Isabella in the Music Room of her 152 Beacon Street home.