One sunny morning, Artists-in-Residence Heather Ackroyd and Dan Harvey sat in the Long Gallery looking at illuminated manuscripts. Ackroyd & Harvey are known for creating works that intersect art, activism, architecture, biology, ecology, and history. Their artworks are often site-specific and connect directly to their interest in local ecologies and planetary environmental concerns. Although they use a variety of natural materials, the artists may be best known for their photosynthesis photographs—photographs that are embedded into seedling grass as it grows.

Photo: Courtesy the artists

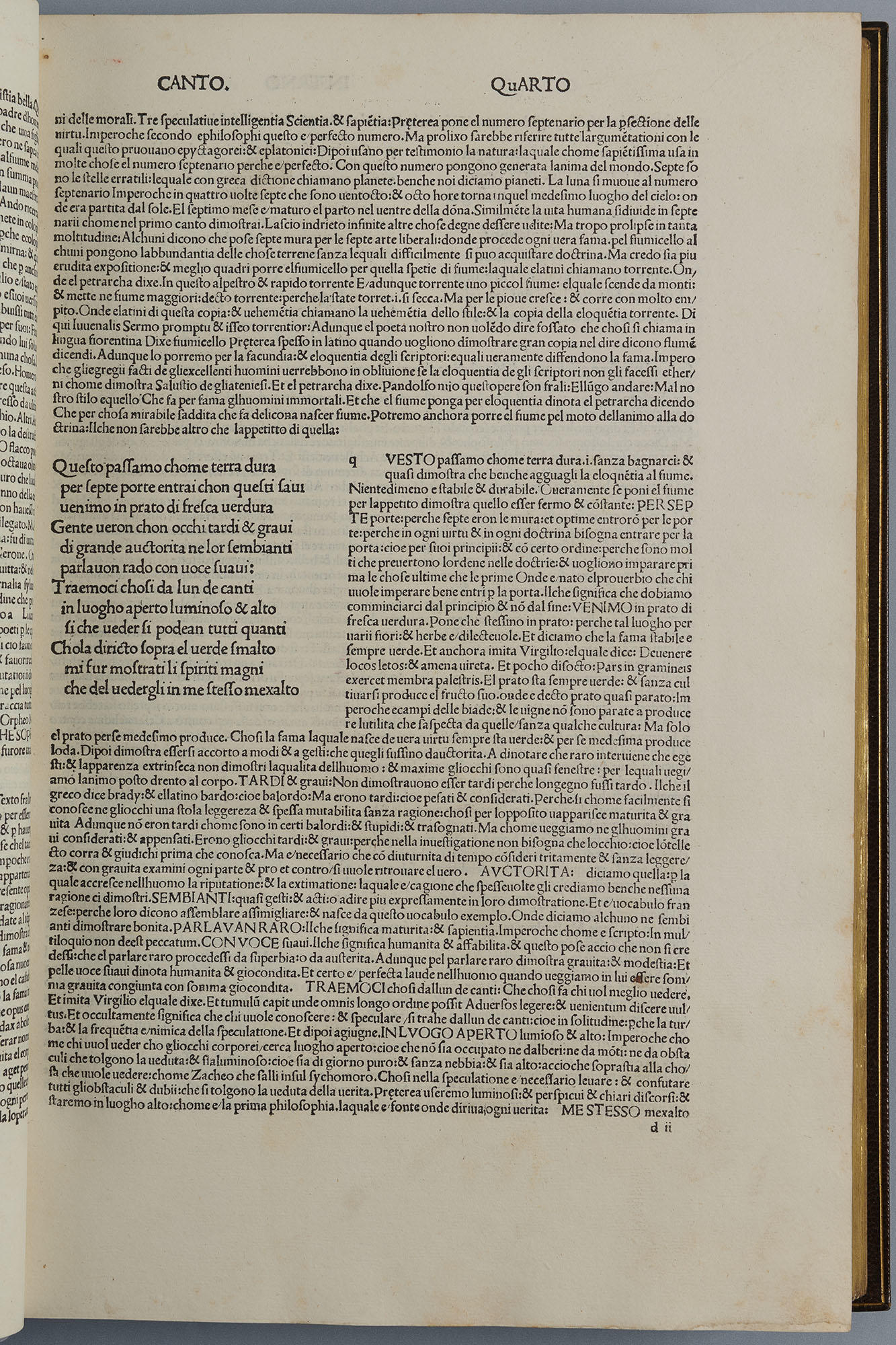

Ackroyd & Harvey had been invited to live, think, and explore the Gardner Museum for a month. The British team spent time in the galleries, conservation labs, and archives researching source material and taking photographs they would use to create work for an exhibit later that year. On that day while looking at books from the large wooden bookcase, an edition of Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy (La Commedia) with a commentary by Cristoforo Landino printed in 1487, stood out for them.

We've had a long-term relationship with Italy and Venice. Somehow it seemed a fitting book to look at. It’s a world-regarded masterpiece and here we were looking at a first edition. Knowing that it was once John Ruskin's book was very special as well. Ruskin wrote The Stones of Venice about Venetian art and architecture so it really, really caught our imagination.

The Divine Comedy—by Dante Alighieri is considered one of the most important poems of the Middle Ages and the greatest literary work in the Italian language. In the three part work, Dante is guided by the spirits of the Roman poet Virgil through Hell (Inferno) and Purgatory (Purgatorio), and Dante’s muse Beatrice through Paradise (Paradiso). In addition to Ackroyd & Harvey, it inspired the likes of William Shakespheare, T.S. Eliot, and Jorge Luis Borges. It is not surprising that Dante’s Divine Comedy also resonated with Isabella Stewart Gardner.

Photo: Sean Dungan

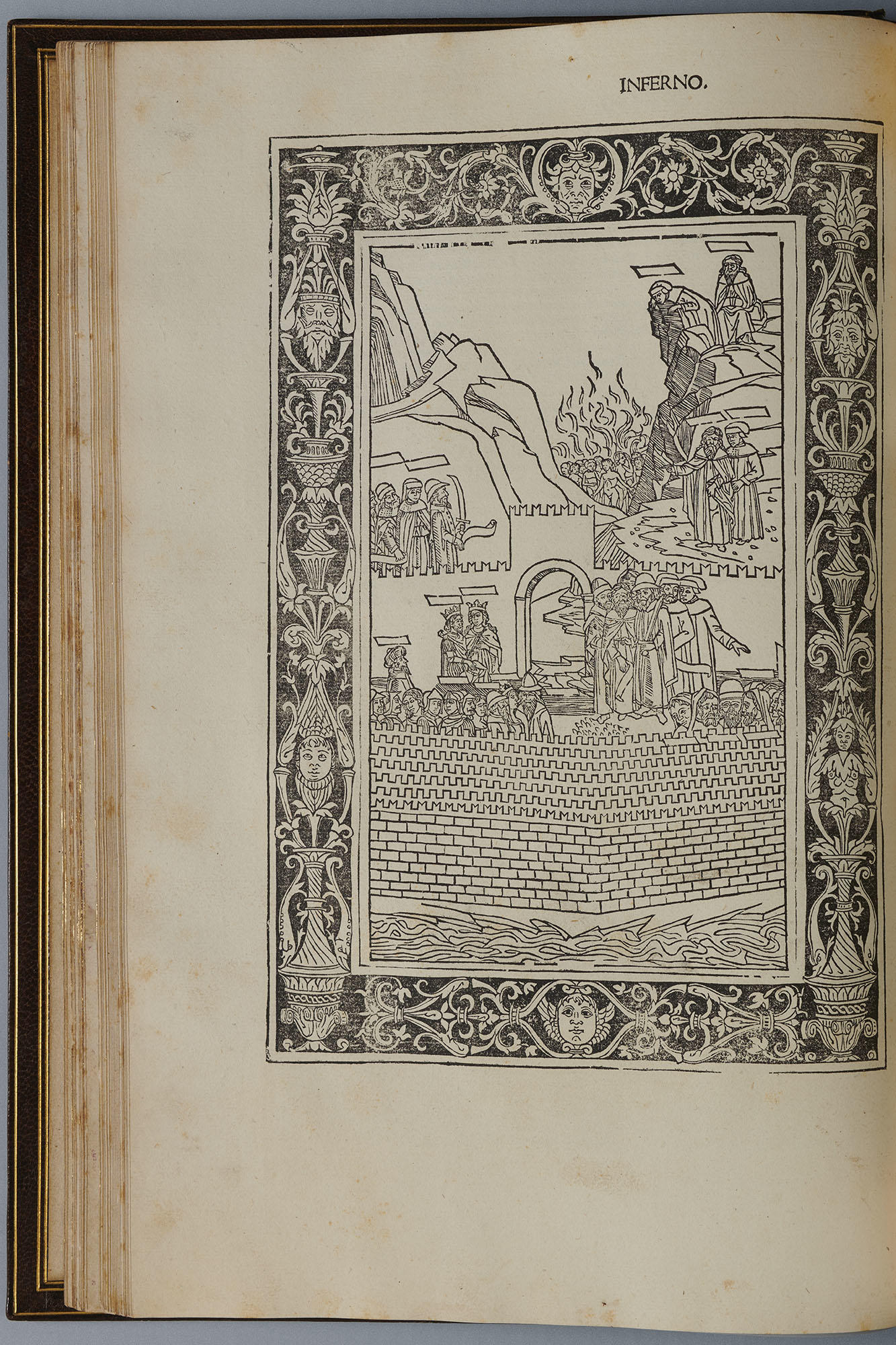

The 1487 edition of Divine Comedy that caught Ackroyd & Harvey’s eye is illustrated with three illuminated pages and a series of woodcuts inspired by Renaissance goldsmith Baccio Baldini's engravings after Sandro Botticelli. The layout is unique, incorporating commentary by Cristoforo Landino (1424–1498) a professor of poetry and rhetoric at the University of Florence. His analysis of the work, printed in this volume as separate blocks of texts in a smaller Roman typeface, was influential and widely used for over a century after the Divine Comedy was first published in 1481.

While perusing the book, Ackroyd & Harvey paused on a passage in Canto IV of the Inferno. Here Virgil and Dante have entered the first circle of Hell, Limbo, where they encounter the souls of virtuous pagans—unbaptized children, heroes, pre-Christian philosophers and scientists, all in a state of sorrowful yearning, yet not subjected to physical pain and punishment. The pilgrims are joined by the great poets of antiquity: Homer, Horace, Ovid, and Lucan, and walk to a castle which is encircled by a river and seven walls with seven gates and a green meadow at its center. From here Virgil and Dante observe the souls.

Ackroyd & Harvey were delighted: When we got to Canto IV, we were reading about the pagans, all of these good souls populating an eternal meadow of green. We couldn't quite believe it when we read it—the evergreen meadow we never knew existed. We were working with scientists in Wales at the time and using a grass that stays green, even in the state of near death. We just thought, ‘this passage is so resonant,’ and we decided to photograph a section and make a negative.

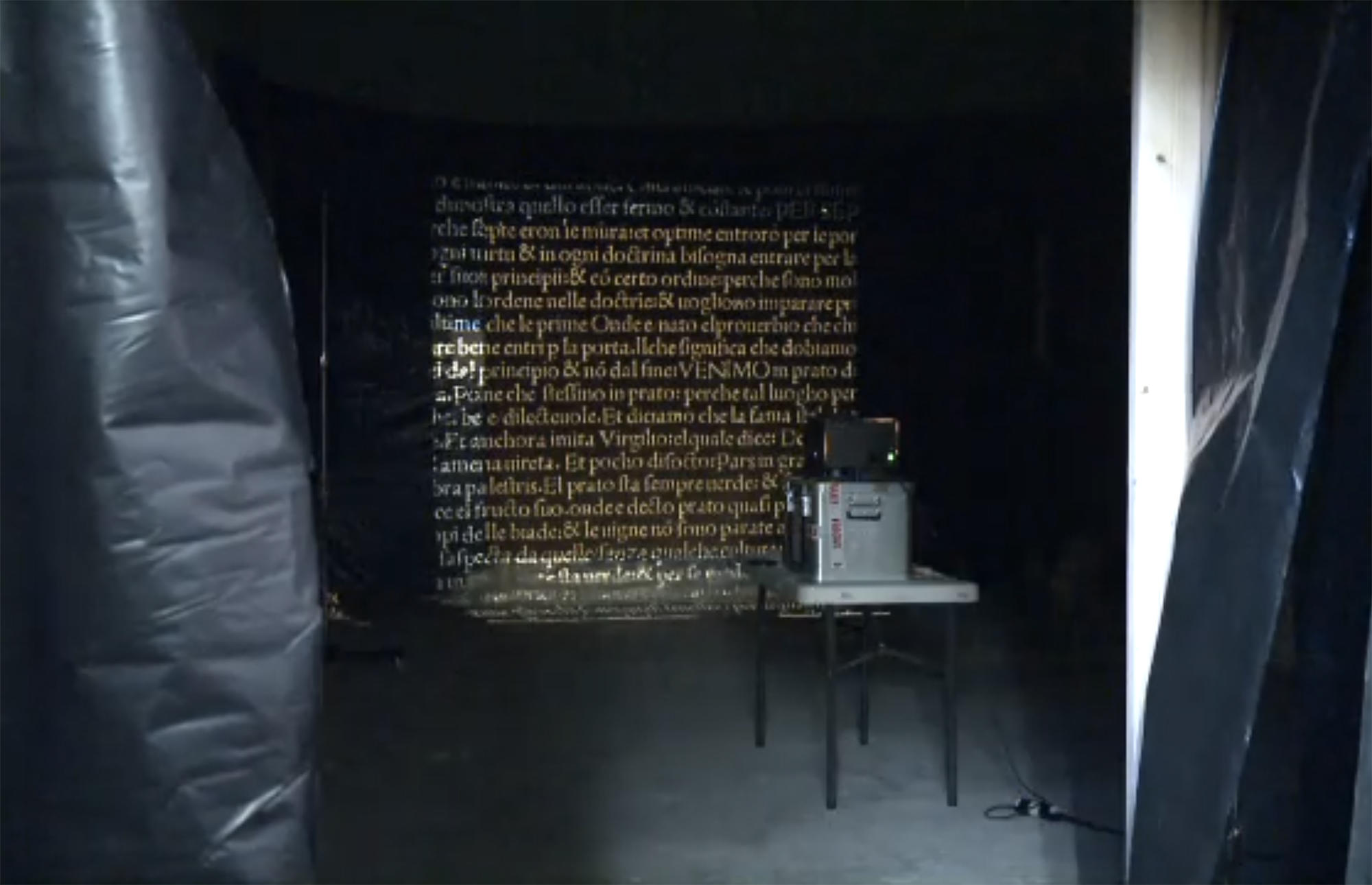

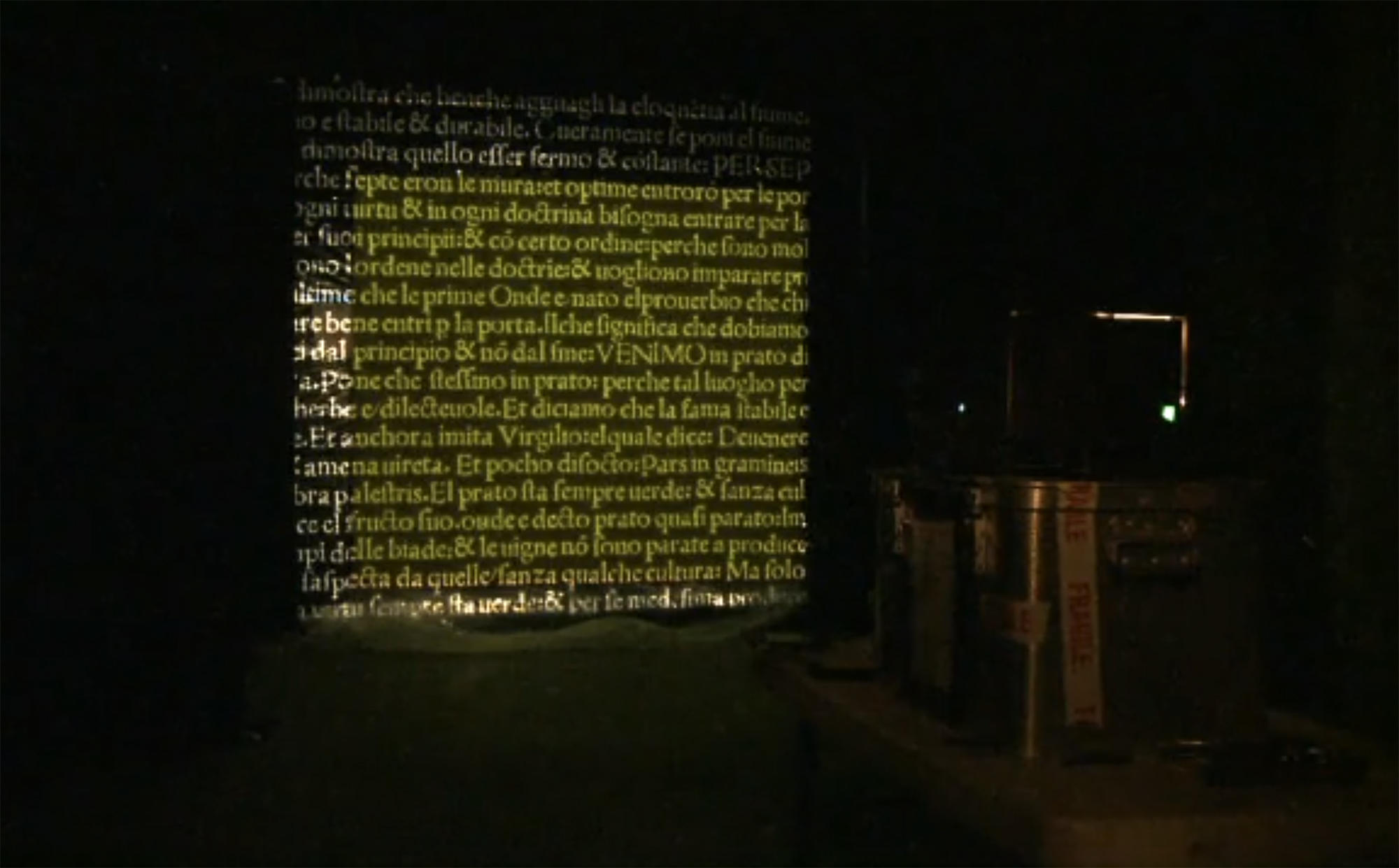

Ackroyd & Harvey’s artistic process is similar to that of black and white photography but instead of a gray-scale they work with the controlled use of chlorophyll, or a green scale. Using a specialized paste they adhere a mixture of seedlings to a canvas. The combination provides a highly light-sensitive surface on which to project the image. The grass photographs are grown in the dark, only receiving light from a projected negative. Where the light is stronger more chlorophyll is produced and the grass is greener. Where the light is dimmer the blades will be less green. Where there is no light they will grow but stay yellow. As the small, embryonic kernels germinate and mature the image is embedded into the living material. With this technique the artists are able to create complex images on a small to large scale.

“The image in our photosynthesis works is on a molecular level. The image, or the portrait, of the person is actually inhabiting the grass. We think it just brings up lots of questions about the true nature of ourselves within nature, within landscape as well. There's something very beautiful about that. If you actually study the structure of the chlorophyll molecule, it's almost the same as the heme molecule in our blood—the atom bound at the center of chlorophyll is magnesium, and iron is held at the center of blood.”

However, the ‘stay-green’ image in the photosynthesis photographs can only be “fixed” for so long and will fade in time when it comes into contact with light. The degradation can be reduced by drying the grass and exhibiting the pieces in low lighting but ultimately the work is ephemeral.

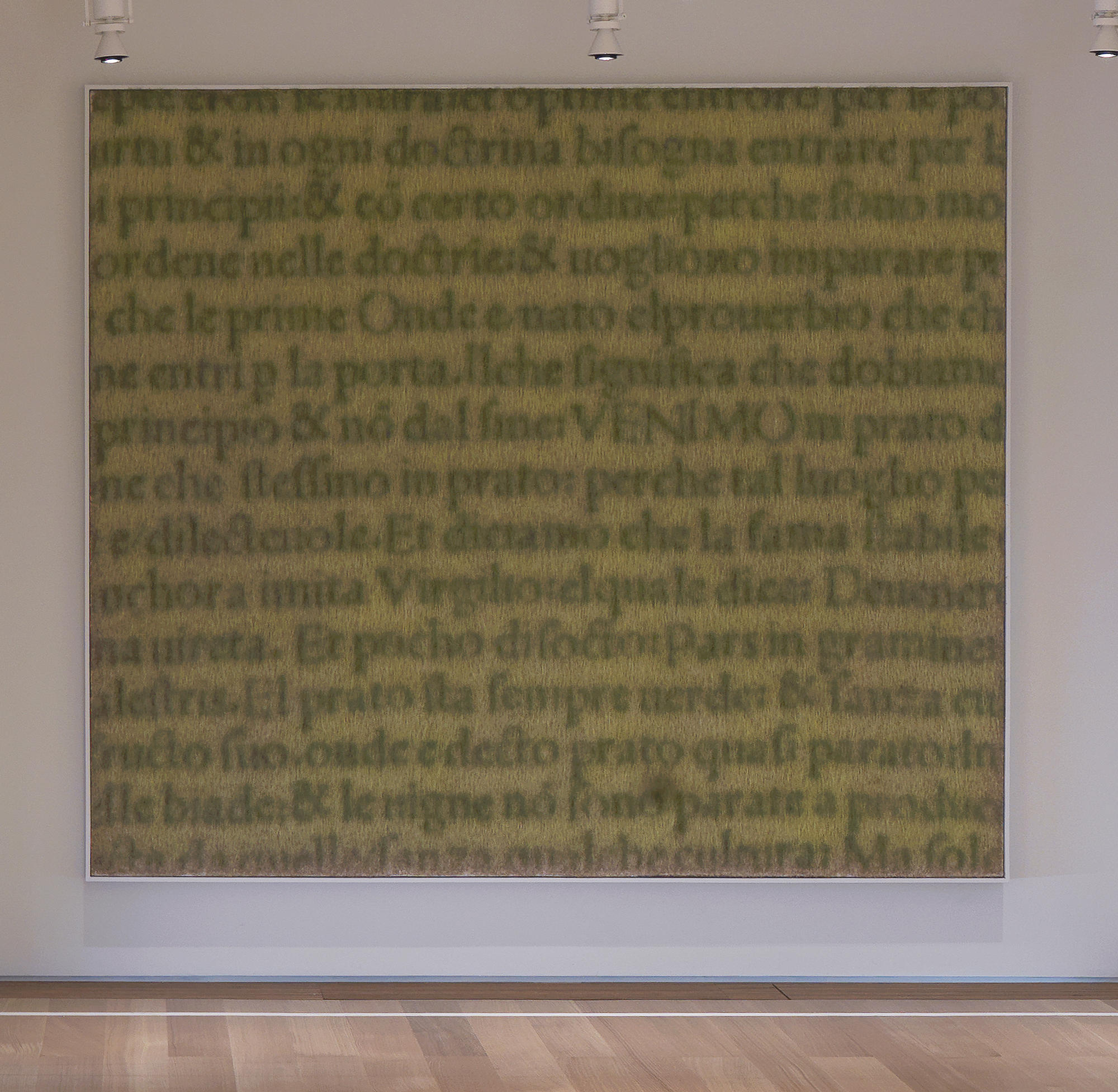

In late September of 2001 Ackroyd & Harvey returned to the Gardner to begin work on their exhibition. Script, measuring 8’x 7’, was one of seven works they grew in the special exhibition gallery which they had temporarily turned into a darkroom. They enlarged a section of Canto IV describing Dante’s discovery of the green meadow which “is always green and produces its own fruit.” The passage includes VENIMO, “we came,” in bold, uppercase letters as if to underscore the shock Dante encountered in finding such vibrancy in the doom of the underworld. Script was the first time the artists had worked with a passage from a book to create an artwork and only the second time they had used text. The slightly organic typography worked beautifully because of its graphic nature.

Looking back on the experience the artists commented: It's always a special moment when we see the positive imprint after we've been projecting the negative, there's always that kind of excitement and revelation in seeing the image. It's never quite as you imagine it… You never know what you're going to get until you see it but it grew beautifully. It really did. We created this piece for the first time at the Gardner right after 9/11 so the cataclysm of this hellish event felt very, very tangible. That those huge buildings were reduced to ash by an inferno. We had our young child with us at the time, four years old. So again, there was this feeling about the fragility of life, but also these completely unexpected turns that can just be so devastating. It spoke to us on numerous levels.

Script was regrown at the Gardner by Dan Harvey in 2012 for the Museum’s inaugural exhibition of the Renzo Piano building.

Photo: Stewart Clements

Ackroyd & Harvey, Script, 2001/2012. Seedling grass (fescue, native, rye), clay, hessian; image imprinted through process of photosynthesis, 8’ x 7’

In 2023 they returned again to grow three new works for the special exhibition Presence of Plants in Contemporary Art, on view June 22–September 17,2023. One of the works for the exhibition titled Satanic Formula is based on an equation calculated by Dr. Ranil Senanayake to show how fossil fuels used by humans are producing new carbon dioxide, accelerating global warming, and generating a proportionate reduction in the ability of life to express itself on this planet. Thus, creating a literal Hell on Earth akin to Dante’s voyage through the inferno.

You May Also Like

Explore the Exhibition

Presence of Plants

Read More on the Blog

The Story of Bus Park: Nari Ward

Read More on the Blog

Isabella and the Dante Society