As part of a year-long journey throughout Asia, Isabella Stewart Gardner and her husband, John “Jack” Gardner, disembarked at Calcutta (Kolkata), the seat of the British Crown rule (1858–1947) on the Indian subcontinent, on 21 January 1884. Isabella recorded her impressions in letters, journals, and two albums (v.1.a.4.10 and v.1.a.4.11) composed primarily of professional and amateur commercial photographs collected at various sites. The albums reveal intimate glimpses of her artistic tastes as well her status as an American following in colonial footsteps.

Fellow Wanderer: Isabella Stewart Gardner’s Travel Albums (Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2022), p. 93

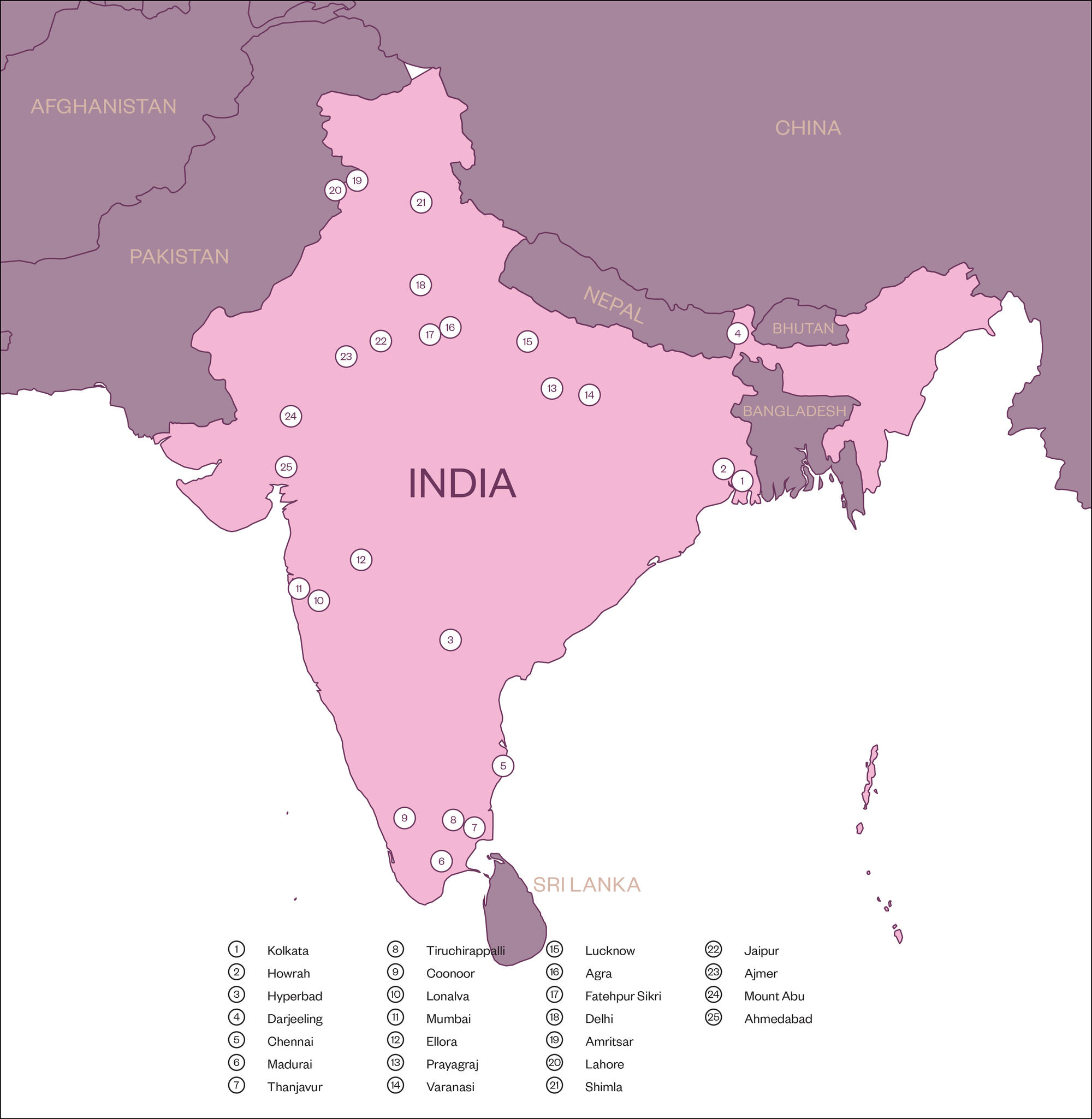

Map of Isabella and Jack Gardner’s travels in India, 1884

Hidden Figures

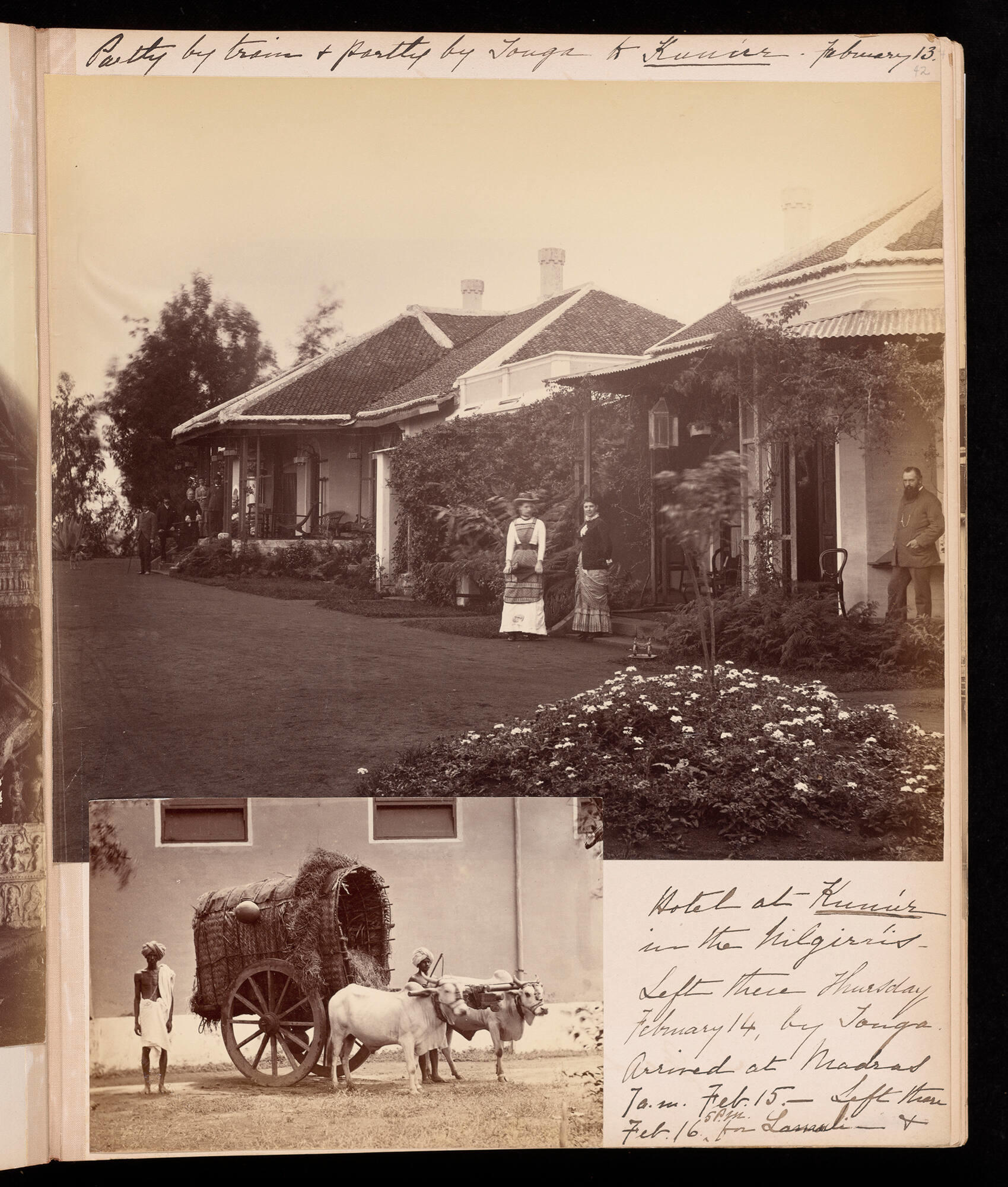

Like many of those privileged enough to travel during this period, Gardner’s albums were created to preserve personal memory. In the album page devoted to her 14–16 February stay in Nilgiri Hills of southern India, she includes a typical image of white travelers enjoying the grounds of the Glen View Hotel but then pierces its bottom frame with one of Indian men—presumably outside the hotel enclosure—with an oxcart, conveying hay. This is just one of several instances in which Gardner inserts unexpected, associative dimensions in her albums, slightly outside the bounds of contemporary colonial decorum.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (v.1.a.4.10)

Isabella Stewart Gardner (American, 1840-1924), Travel Album: India, Volume V, 1884. Bound album with collected photographs, page 42, showing the Glen View Hotel and Indian men with an oxcart in the Nilgiri Hills

In her albums, Isabella is more explicit in seeking out and including images of palanquins (covered litters carried by men)—which by the 1860s had all but disappeared from the subcontinent—somehow managing to imagine one by a quiet tank (temple reservoir) in the bustling, colonial city of Bombay. She then devotes a page to crudely rendered tourist paintings, characterizing the region’s historical transition to cart and buggy. These images are still products serving an “othering,” Orientalizing gaze, but their inclusion in Gardner’s album continues to suggest her greater interest in India’s pre-colonial past.

From “Parsee [Parsi] Theatre'' to street jugglers, Gardner’s diary reveals consistent delight in what she perceives as “most Eastern,” which, coupled with an exploratory interest in “Eastern” religions, would impact the types of objects she would acquire on her journey. In Calcutta, she would skip the multi-carat gems on offer from the regional courts. Instead, on the advice of a friend, Isabella and Jack visited the famous jeweler and antique dealer Alexander M. Jacob (real name, Iskandar Meliki bin Ya’qub al Birri, 1849–1921), from whom she acquired two bazubands (armbands), “certified to have belonged to the Queen of Delhi!”1 Here, she was referring to Zinat Mahal, the favorite wife of the last Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar II (r. 1838–58), who was sent into exile after the failed Indian Mutiny (also called the Great Uprising) of 1857, whereby authority fully shifted to Crown rule; according to Jacob’s provenance records, the “armlets were taken from King’s palace Delhi during the time of the Mutiny by the British soldiers, and were auctioned by Colonel Innes the prize agent.”2 Like many of her time, Gardner did not seem to grasp the violence that had removed the armbands from their original owner.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (M18w73.1-2). See them in the Little Salon.

Indian, Jaipur, Pair of Armlets (Bazubands), about 19th century. Gold on a lac core, with precious and semi-precious stones, enamel decoration, and cords of silk and gold with seed pearls, 22.7 cm (8 15/16 in.)

Gardner was excited that the armlets included the “nine sacred gems,” referencing the navaratna tradition of Indian jewelry, with each gem (pearl, ruby, emerald, diamond, coral, blue sapphire, yellow sapphire, hessonite garnet, and chrysoberyl) corresponding to the nine celestial objects (seven planets and ascending and descending modes of the moon), which in turn provide talismanic qualities to the wearer.3 However, Gardner's armbands include turquoise, which is not one the traditional stones, but was subtly added to the array under the influence of Victorian taste.4 Again, we see Gardner’s intersection with the by-products of the British colonial project, but as much as she is able, she attempts to eschew prevailing conventions in search of something more alternative, and more “authentic.” And when she finally visits one of the key sites of the Indian Mutiny at the Residency in Lucknow, she stays true to spirit, and pastes into her album an image of Indian musicians playing beneath the rubble.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (v.1.a.4.10)

Isabella Stewart Gardner (American, 1840-1924), Travel Album: India, Volume V, 1884. Bound album with collected photographs, page 56, showing a photograph of musicians next to the Residency in Lucknow

Throughout Isabella Gardner’s journey of the Indian subcontinent, we see time and time again the complex, Anglo-Indian context from which her travel albums emerge: visits to the Calcutta International Exhibition, stays in colonial hill stations, and even with the photographers whose images she opts to acquire and paste. At the same time, we see her seeking the essences of India’s pre-colonial past, be it in “authentic” Mughal jewelry, the charms of the palanquin, or street musicians. We can best assess the influence of her journey through India on her museum via her travel albums: instead of using the grid-by-grid approach of contemporaneous architectural historians, she makes sure to arrange her pages in ways that capture the ornament and grandeur of India’s heritage, all the while ensuring each moment elicits personal reflection, and by the very act of an engaged, emotive gaze amid inequality and the balances of progress and decay.

You May Also Like

Read More in the Book

Fellow Wanderer: Isabella Stewart Gardner’s Travel Albums

Visit an Exhibition

Raqib Shaw: Ballads of East and West

Read More on the Blog

An Embroidery from India

1Pedro Mourna Carvalho, “Jewelry and Objects from India,” in Journeys East: Isabella Stewart Gardner and Asia, Exh. cat. edited by Alan Chong and Noriko Murai (Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2009), 458.

2Ibid., 458n6.

3Usha Balakrishnan, Alamkara: The Beauty of Ornament (New Delhi, 2014), 214.

4Carvalho 2009, 458.