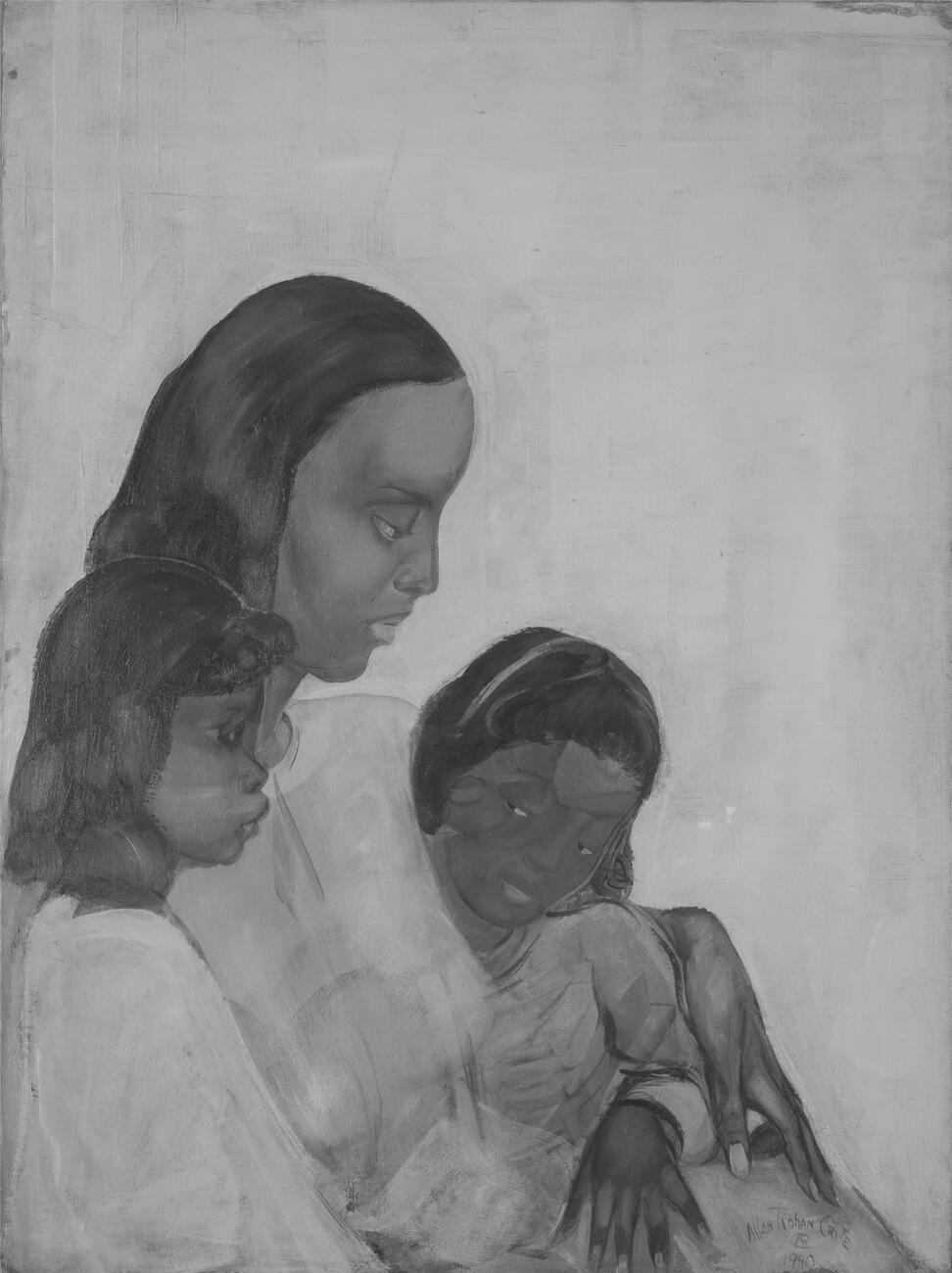

Beginning in Fall 2024, five paintings by Allan Rohan Crite were treated by Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum conservators in collaboration with the lending institution, The Museum of African American History (MAAH), for Allan Rohan Crite: Urban Glory (October 23, 2025—January 19, 2026). Among these works was Untitled (Mother and Children), completed by Crite in 1940. At a glance, this appears to be a straightforward composition. It depicts a woman seated in profile in front of a flat blue background with two children, one tucked against each side of her body. However, while investigating this work in the Gardner’s Conservation Lab, we quickly found that there was much more to learn from this piece about Crite’s artistic process.

Museum of African American History Boston | Nantucket. Courtesy of the Allan Rohan Crite Research Institute and Library. Photo: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Allan Rohan Crite (American, 1910–2007), Untitled (Mother and Children), 1940. Oil on canvas board, 61 x 45.7cm (24 x 18 in)

About the Artist

Allan Rohan Crite (1910–2007) was a Boston-based American artist. Born in 1910 in Plainfield, New Jersey, he and his family later relocated to Boston’s Lower Roxbury neighborhood. He visited the Gardner Museum for the first time as a student around 1919, and later trained as an artist at the neighboring School of the Museum of Fine Arts, now the SMFA Tufts, finishing around 1936. He lived and worked in the city for the rest of his life, both as an artist in his own right and as a draftsman at the Boston Naval Shipyard.

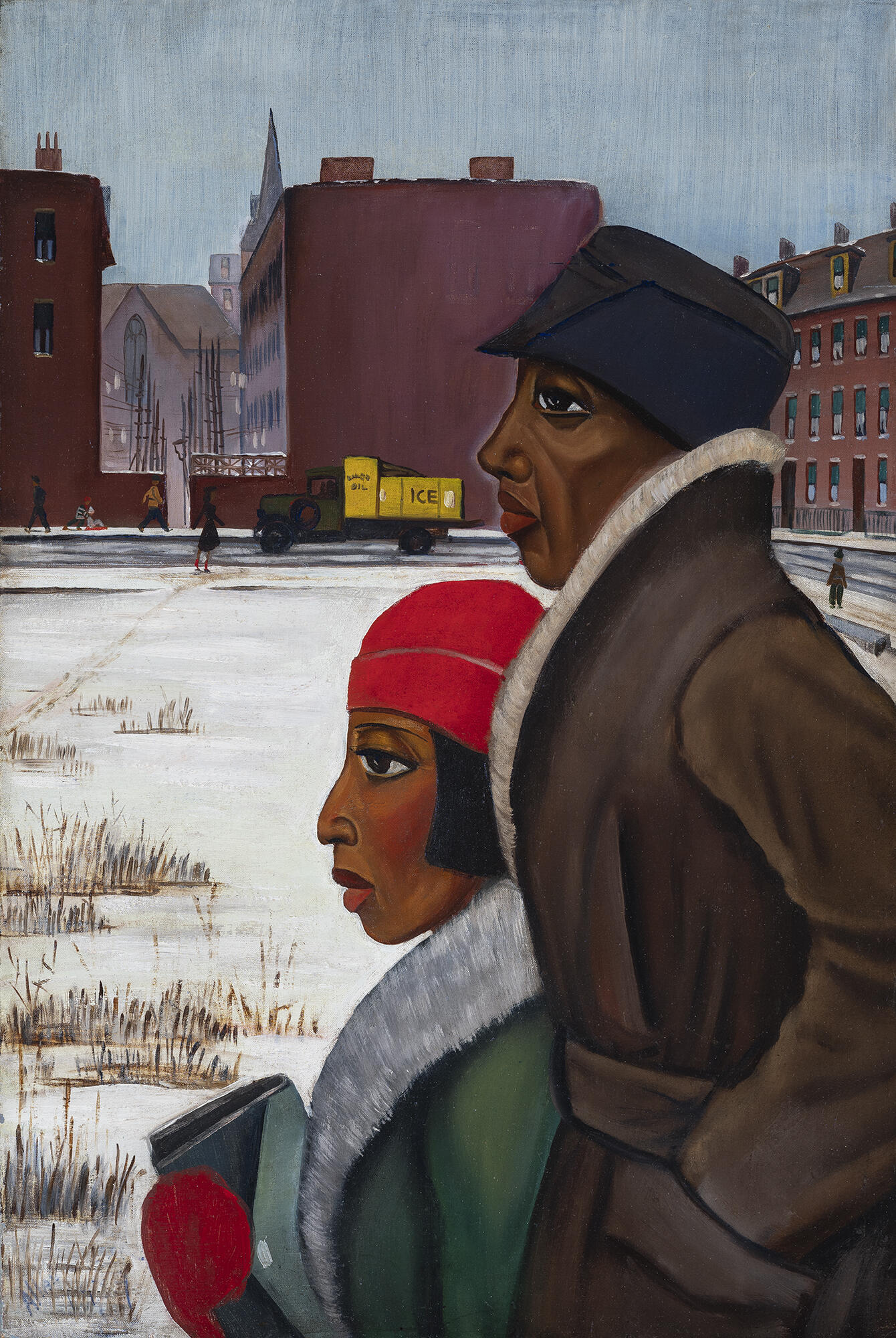

My intention in the neighborhood paintings and some drawings was to show aspects of life in the city with special reference to the use of the terminology "Black" people and to present them in an ordinary light, persons enjoying the usual pleasures of life with its mixtures of both sorrow and joys . . . I was an artist-reporter, recording what I saw.

Crite was most active as a painter in the early part of his career, when he spent significant time documenting the scenes and people of his Boston neighborhood. He later pivoted to mostly creating prints and works on paper in the late 1940s. The focus of this particular treatment, Untitled (Mother and Children), was painted in 1940, falling towards the end of Crite’s oil painting career.

Museum of African American History Boston | Nantucket. Courtesy of the Allan Rohan Crite Research Institute and Library. Photo: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Allan Rohan Crite (American, 1910–2007), Ice, May 1939. Oil on canvas board, 76.2 x 50.5 cm (30 x 19 7/8 in.)

Conditions and Suspicions…

One of the key tenets of conservation practice is documentation. Therefore, we began this treatment by photographing the painting in both visible light and in raking light to help us to evaluate and document its condition. We could see that paint layers were applied in a manner showing raised brush work, and the raking light showed surface texture and brush marks not associated with the visible painted composition. This indicated to us the possible presence of another painting below this one, so we used the tools we have at the museum to investigate further. First up: infrared photography.

Infrared Photography

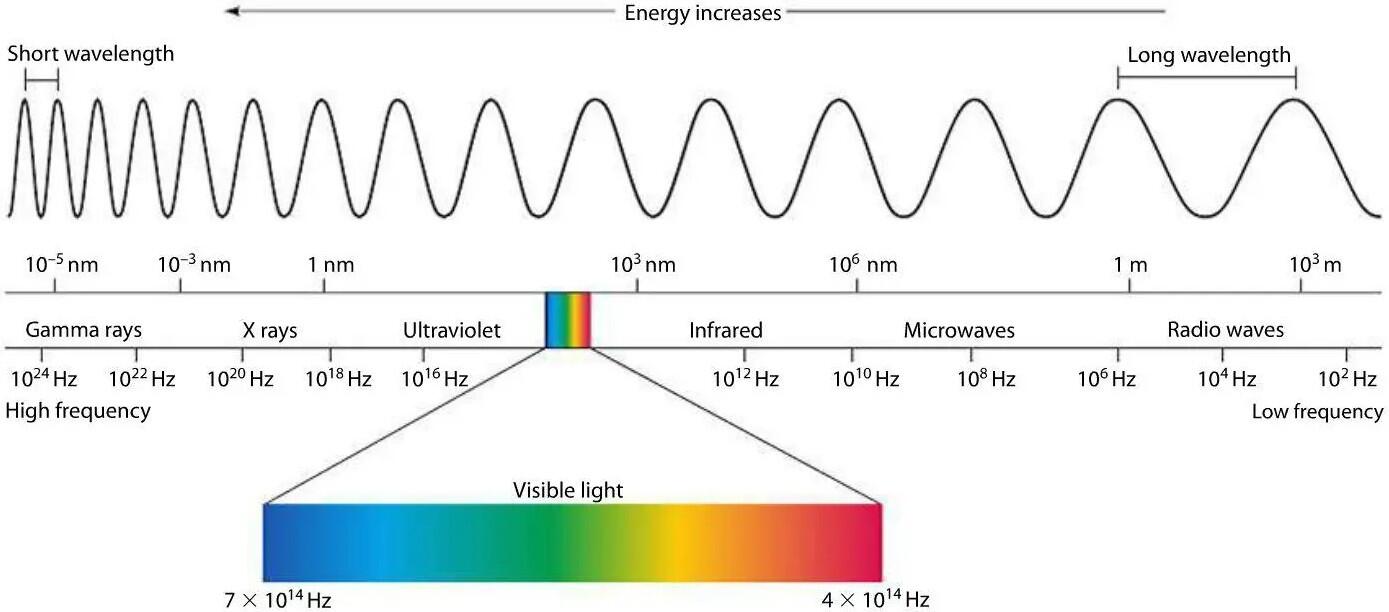

On the electromagnetic spectrum, infrared (IR) rays are just outside of the wavelengths the human eye can see as visible light. The shortest IR wavelengths, between 700 and 3000 nanometers (nm), tend to be most interesting to art conservators. Many paints and pigments that are opaque in visible light become transparent at these wavelengths. In contrast, carbon-based media such as charcoal, graphite, and many black pigments remain visible. This allows conservators to “see through” the paint layers, and in some cases even view under drawings.

The Electromagnetic Spectrum, NASA

Because the human eye cannot see infrared on its own, some conserverators—including our team at the Gardner Museum—use a digital camera with a special sensor modified to detect ultra violet (UV), visible light, and infrared (IR). This method of IR photography visualizes the wavelengths just outside of visible light—between 700nm and 900nm.

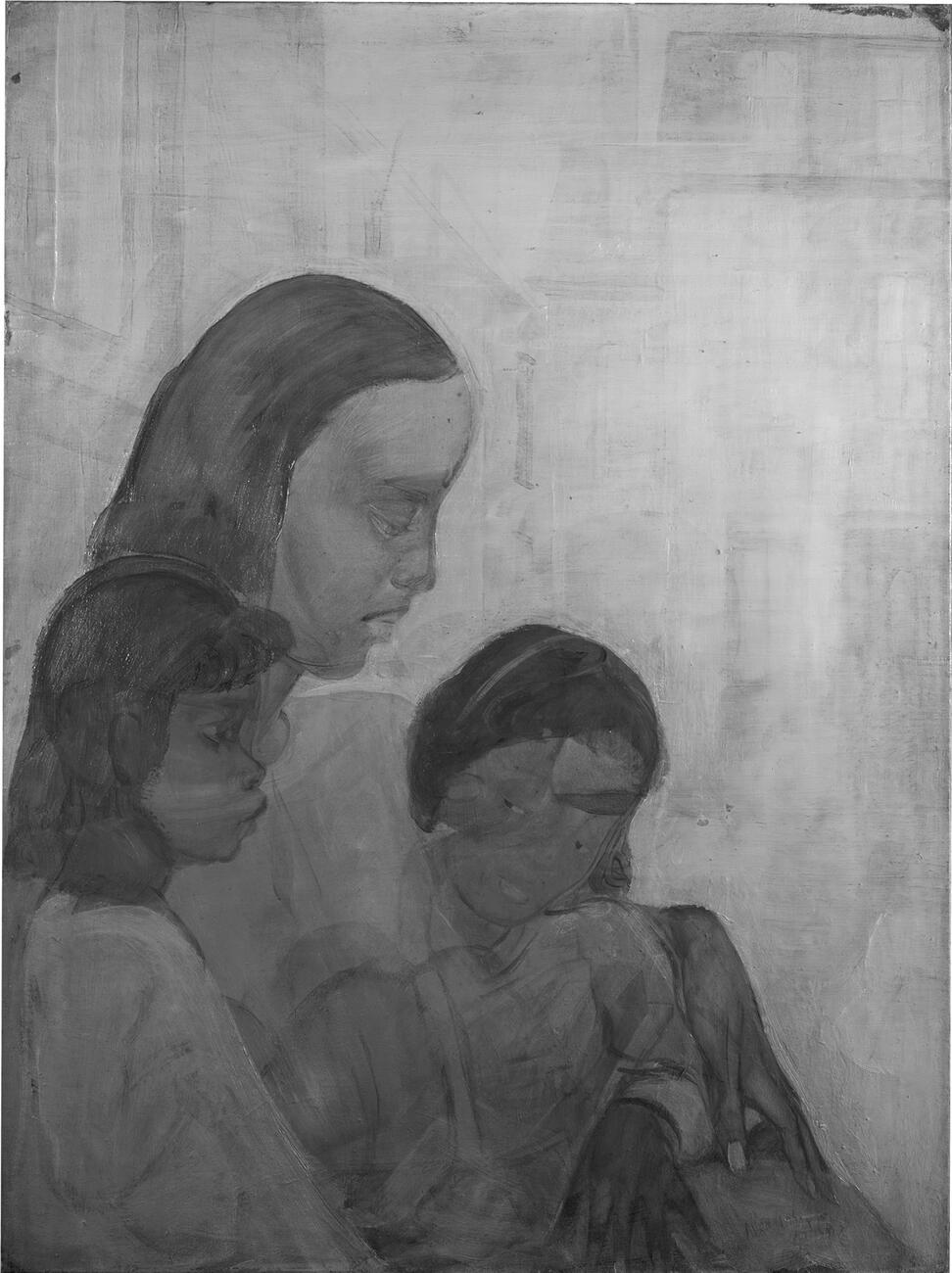

The results of the IR photography are subtle, but looking carefully we can see what appear to be underdrawing lines made with a dry media, like charcoal, as well as wet media, like paint. There is evidence of some repositioning and refining of the figures in the foreground, particularly in the facial features of the child on the viewer’s left and the mother’s clothing and hand. There also seems to be a form painted underneath the face of the righthand figure—perhaps another figure in a different position—as well as large geometric shapes in the background of the piece.

Photo: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Allan Rohan Crite (American, 1910–2007), Untitled (Mother and Children), 1940, infrared and visible light photographs

Museum of African American History Boston | Nantucket. Courtesy of the Allan Rohan Crite Research Institute and Library.

So, while this analysis answered our broader question—Yes! There is definitely something under the top layer of paint!—it didn’t provide enough information to reveal exactly what is under that layer. We needed to look closer.

Infrared Reflectography

Around this time, the Gardner was fortunate to host visiting scholar and paintings conservator, Roxane Sperber of Newfields in Indianapolis. She came to the Museum to examine paintings related to her research using something called the Opus Instruments Apollo IRR camera.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Roxane Sperber places a painting, The Dauphin François D'Angouleme, after Corneille de Lyon (Netherlandish, 1500–1510—1575), on an easel for IRR analysis

While our in-house infrared photography uses a modified digital camera, infrared reflectography (IRR) is different. It uses specialized equipment to detect the infrared wavelengths beyond the 900nm our camera is sensitive to. The Apollo IRR camera visualizes infrared wavelengths from 900 nm to 1700 nm, exposing even more detail beyond the visible spectrum.

Photo: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Allan Rohan Crite (American, 1910–2007), Untitled (Mother and Children), 1940, infrared reflectograph and visible light image

Museum of African American History Boston | Nantucket. Courtesy of the Allan Rohan Crite Research Institute and Library.

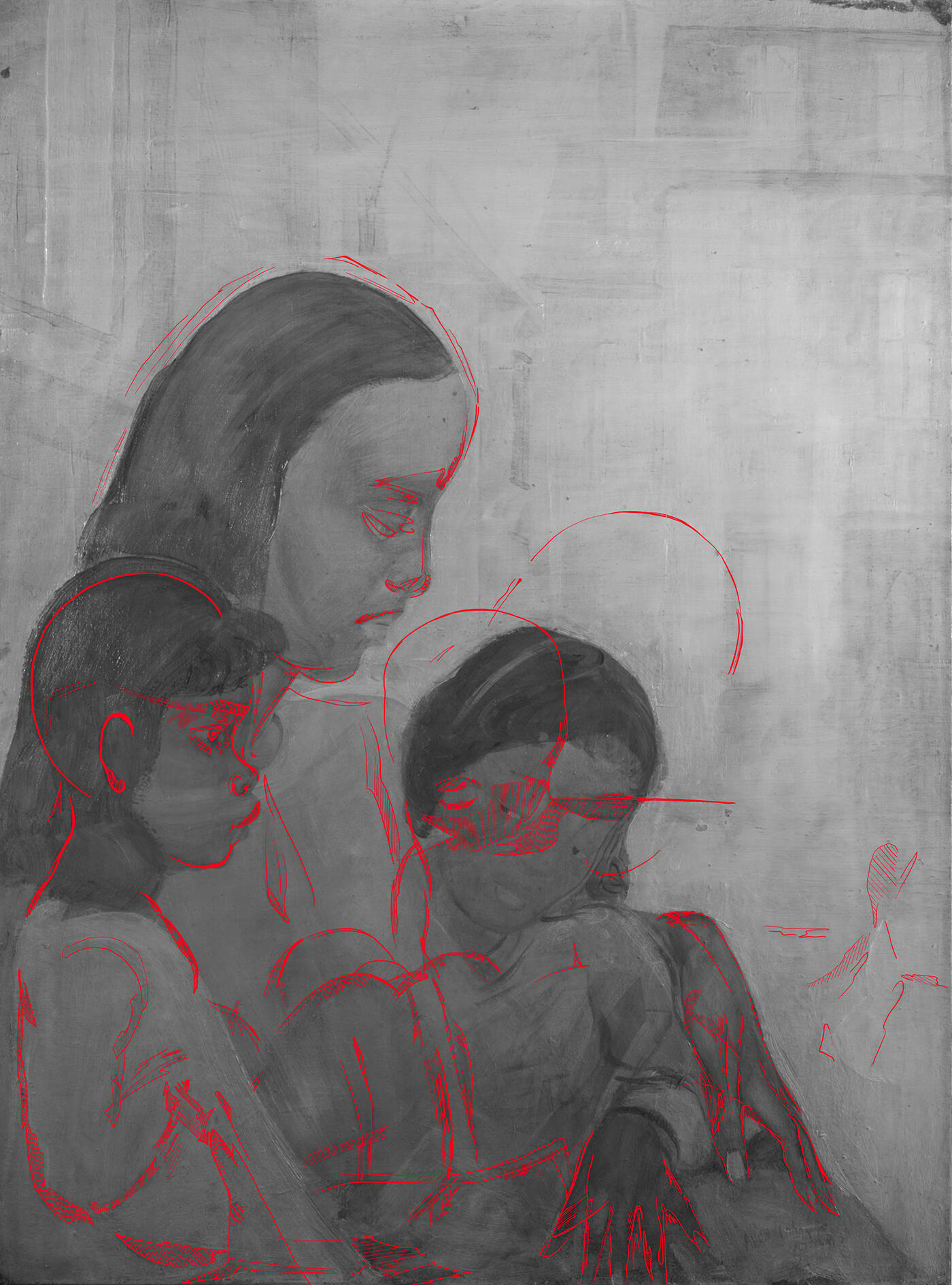

This imaging method clarified what is going on beneath the surface of this painting. Newly visible under drawings show Crite’s extensive refinements of the figures, such as where he changed the face and the arm placement of the figure to the left of the painting. In an earlier version, the figure on the right was a baby or a very small child, held by the central mother figure. This child was fully overpainted and is no longer visible in the final painting.

Photo: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Allan Rohan Crite (American, 1910–2007), Untitled (Mother and Children), 1940, infrared reflectograph with interpretive overlay to highlight figural underdrawing in red

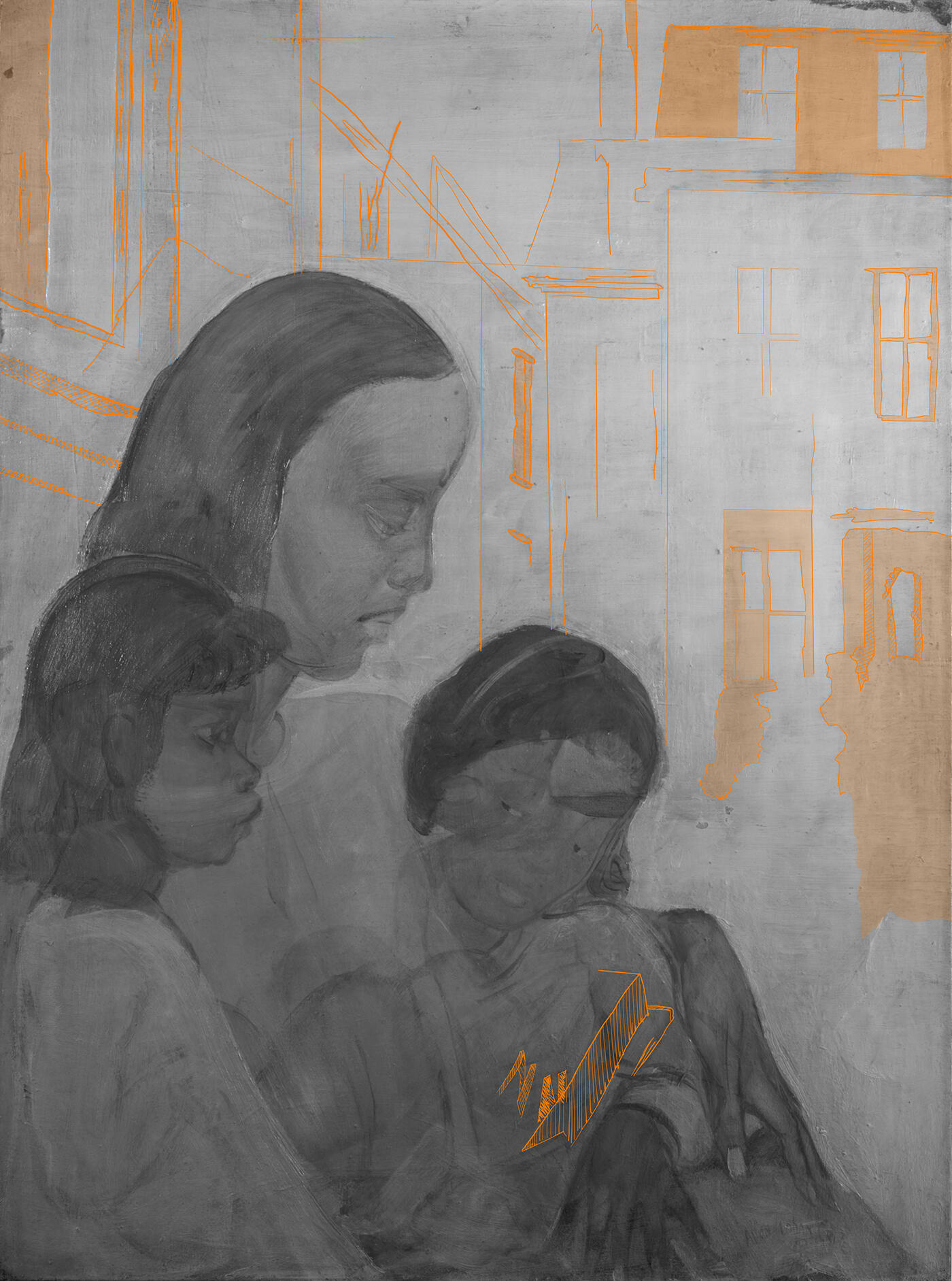

In the background of the image, the IRR shows buildings typical of Crite’s South End street scenes. Looking closely, we can also see where some of these architectural elements appear to be layered underneath the figures, like a set of stairs painted below the righthand figure.

Photo: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Allan Rohan Crite (American, 1910–2007), Untitled (Mother and Children), 1940, infrared reflectograph with interpretive overlay to highlight architectural underdrawing and under painting in orange

So what does all this mean? We can never know exactly why Crite reworked the painting so significantly, nor which versions of the painting coexisted. Perhaps this mother and her children were initially posed in a street scene, or maybe Crite just used an unfinished street scene as a canvas (or in this case artist’s board) for a totally new work. However, it does show that Crite reused materials—which means there may be many more hidden paintings below the surfaces of his finished pieces. This is an exciting future direction for technical research into an artist who—to date—has not been extensively studied by conservators.

Come see this painting, and other works by Crite, at Allan Rohan Crite: Urban Glory, October 23, 2025 – January 19, 2026 at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum or in the exhibition catalogue, Allan Rohan Crite: Neighborhood Liturgy. And perhaps, after future research, we will be able to share other hidden Crite works!

You May Also Like

Explore the exhibition

Allan Rohan Crite: Urban Glory

Read More on the Blog

A Technical Study of a Guanyin Sculpture

Read More on the Blog

Botticelli’s Virgin and Child: Infrared and Ultraviolet Light