Last year, the Gardner’s exhibition Boston’s Apollo focused on the life of Thomas McKeller, a Black artist’s model, veteran and Roxbury resident. He posed for many of the figures in a mural at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston commissioned from painter John Singer Sargent. McKeller’s role in the project was not common knowledge because Sargent had transformed his body into white gods, goddesses and other allegorical figures. Many visitors to the exhibition asked whether other Black models posed for artists who undertook similar transformations. Yes, but we only know of a few instances in which the model has already been identified. No doubt more remain to be discovered.

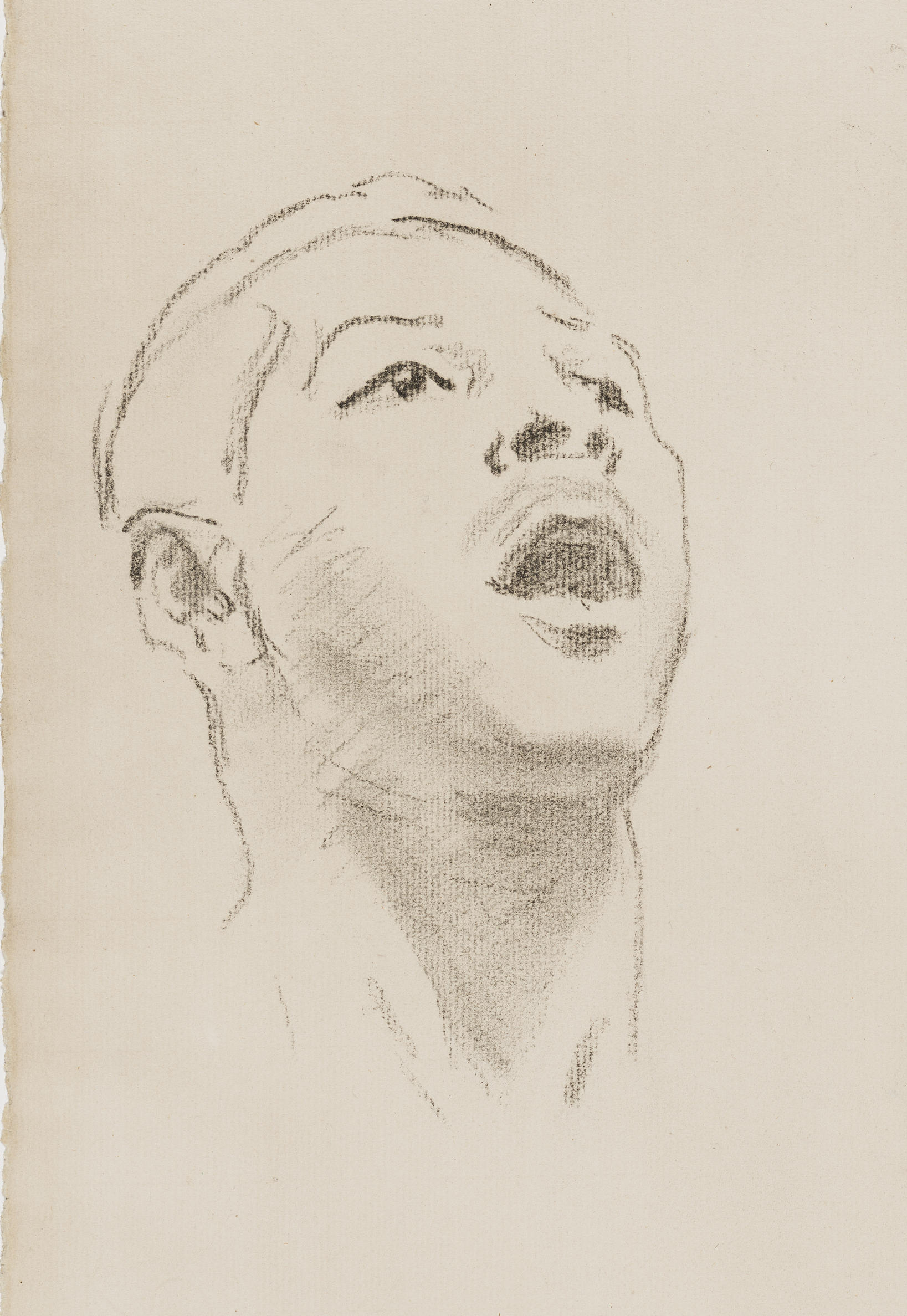

Thomas McKeller in John Singer Sargent’s Study for Classic and Romantic Art for the Rotunda of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (detail), 1916–1921

© 2019 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

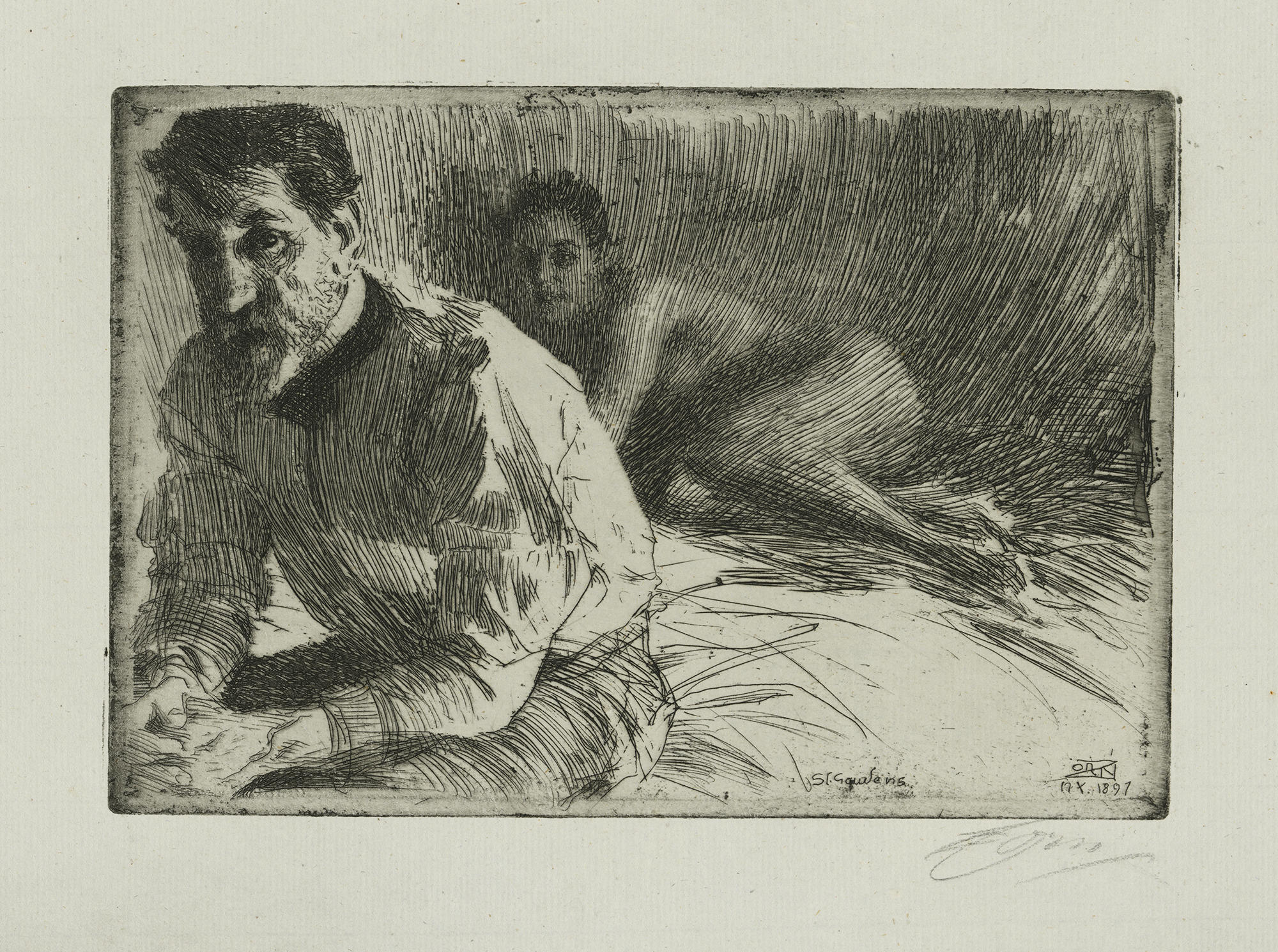

Hettie Anderson is a good example. She is the woman in this etching by the Swedish painter Anders Zorn, who gave this work to his friend Isabella Stewart Gardner in 1897. Anderson, nude, lounges on the bed behind sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. The context is suggestive, as if we are witnessing two lovers in a bedroom.

Anders Zorn (Swedish, 1860–1920), Augustus Saint-Gaudens II, 1897. Etching

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. See it in the Short Gallery

Little is known about her life. Harriet (also known as Harriette, Hattie, or Hettie) Lee Dickerson was born in 1873 in Columbia, South Carolina into a family of free African-Americans. By 1895, she was in New York City modelling at the Art Students League, renting an apartment at 698 Amsterdam Avenue, and using the last name Anderson. Some census records list Anderson as white and she did not describe her race to others, so far as we know.

Anderson modelled for several artists including painter John La Farge, who relied on Hettie for a figure in his Bowdoin Museum murals, and sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. It remains unclear how they met. By 1897, Saint-Gaudens had been working on a monument to General William Tecumseh Sherman for several years and chose Anderson to model for the figure of Winged Victory. In January, Saint-Gaudens wrote to his niece, the landscape architect Rose Nichols, “Next week I commence the nude of Victory from a South Carolinian girl with a figure like a goddess.” The sculptor admired her beauty, describing her as “the handsomest model I have ever seen of either sex, and I have seen a great many.”

She also posed for the artist’s friends and associates. Very likely, Saint-Gaudens introduced Anderson to Zorn when the painter was visiting America in the 1890s. She probably posed for his studio assistant Adolph Alexander Weinman, for the statue of Fame atop the New York Municipal Building (now David N. Dinkins Manhattan Municipal Building).

Anderson was even immortalized on a coin. In 1906, President Roosevelt commissioned Saint-Gaudens to create coins that rivaled those of ancient Greece. For the twenty dollar gold coin, he created a figure of Liberty borrowed directly from the Sherman monument’s figure of Victory with slight modifications.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens (American, 1848–1907, designer), Double Eagle Twenty-Dollar Gold Coin, 1907. Hettie Andersen was the model for the figure of Liberty.

National Numismatic Collection, National Museum of American History

After Saint-Gaudens died, Anderson refused requests by his family to reproduce a bronze bust of her as Victory that the model kept in her possession. She wrote “Valuing it as a do, and knowing as I do that it is the only one in existence, in that state – I am not willing to have any duplicate made of it, for any purpose whatever. You will realize that if I were to allow it to be copied it would greatly depreciate its value.” Anderson was correct – the Saint-Gaudens family were trying to cash in on the sculptor’s reputation by selling copies of his works. As a consequence of her unwillingness to work with them, she was largely excluded from his biography and legacy, both tightly controlled by the family, and was only later rediscovered by scholars.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens (American, 1848–1907), Bust of Hettie Anderson, 1897

Photograph Archives, Smithsonian American Art Museum and its Renwick Gallery (JUL J0006125). Photo: De Witt Ward, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Later in life Anderson worked as a classroom attendant at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where works by Saint-Gaudens have been in the museum’s permanent collection since at least the 1910s. In 1938, she died and was buried in the Lee family plot at Elmwood Cemetery in Columbia, South Carolina. So much remains to be learned about Hettie Anderson and her contributions to American art. A forthcoming New York Times article will profile her remarkable life, and we hope that a similar light will be shined on those of models like her whose incredible stories deserve our attention.

Read More on the Blog

Thomas Eugene McKeller, John Singer Sargent, and Isabella Stewart Gardner

Explore the Collection

Anders Zorn (Swedish, 1860–1920), Augustus Saint-Gaudens I, 1897

Read More on the Blog

Commemorating Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts Regiment