French Impressionist Edgar Degas (1834–1917) was, by all accounts, both a brilliant artist and a difficult person. There are many anecdotes that illustrate his sometimes impolite behavior with other people.

Image courtesy Clark Art Institute. clarkart.edu

Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas (French, 1834–1917), Self-Portrait, about 1857–1858. Oil on paper, mounted on canvas. Clark Art Institute, 1955.544

One such story comes from the art dealer Amboise Vollard. Towards the end of his life, Degas was progressively losing his sight. This was tragic for the painter, but according to Vollard, he was not above occasionally using his developing disability to his own advantage:

Degas used to pretend to be more blind than he was in order not to recognize people he wanted to avoid. But one day he ran into an acquaintance of thirty years' standing and asked him his name, adding, ‘It's my poor eyes, you know.’ Then he forgot he could not see and pulled out his watch. . . .

Another tale about Degas that shows he was unconcerned about offending others—including those who paid him to paint their portrait—is linked directly to the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. It surrounds a wonderful painting in the collection: Josephine Gaujelin.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P1e4). See it in the Yellow Room.

Edgar Degas (French, 1834–1917), Joséphine Gaujelin, 1867. Oil on canvas, 61.2 x 45.7 cm (24 1/8 x 18 in.)

When Isabella acquired this portrait, the sitter was unidentified. The work went by two titles: either Woman with Clasped Hands or Woman with Golden Raisins, referring to the decoration in her hair. As far as we know, the only time the painting was shown publicly before debuting at the Museum was when Degas himself exhibited it at the 1869 Paris Salon—a major juried art exhibition in Paris. The artist simply titled her Portrait of Mme. G….

Clearly, mystery still abounded when art historian and advisor Bernard Berenson helped facilitate Gardner’s acquisition of the painting in 1904. He wrote:

And how is it with the mysteriously fascinating, inexhaustibly beautiful Degas? It is yours, I hope. If not, I shall be even more disappointed than yourself.

To which Gardner, who had recently purchased the painting from the New York dealer Eugene Glaezner, responded:

Dear friend, I am now mortgaged over my eyes, but am comparatively happy, for the Degas lady with the yellow background is here. Glaezner brought her on, is still happy to leave her here, and will be paid someday! In the meantime, I must still more economize.

Gardner loved the portrait, which was initially installed in the Long Gallery. She continued to mention it in several letters to Berenson over the years, but its model remained unidentified.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Thomas E. Marr & Son (Marr16538)

The Long Gallery, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, 1910, showing Edgar Degas’ portrait

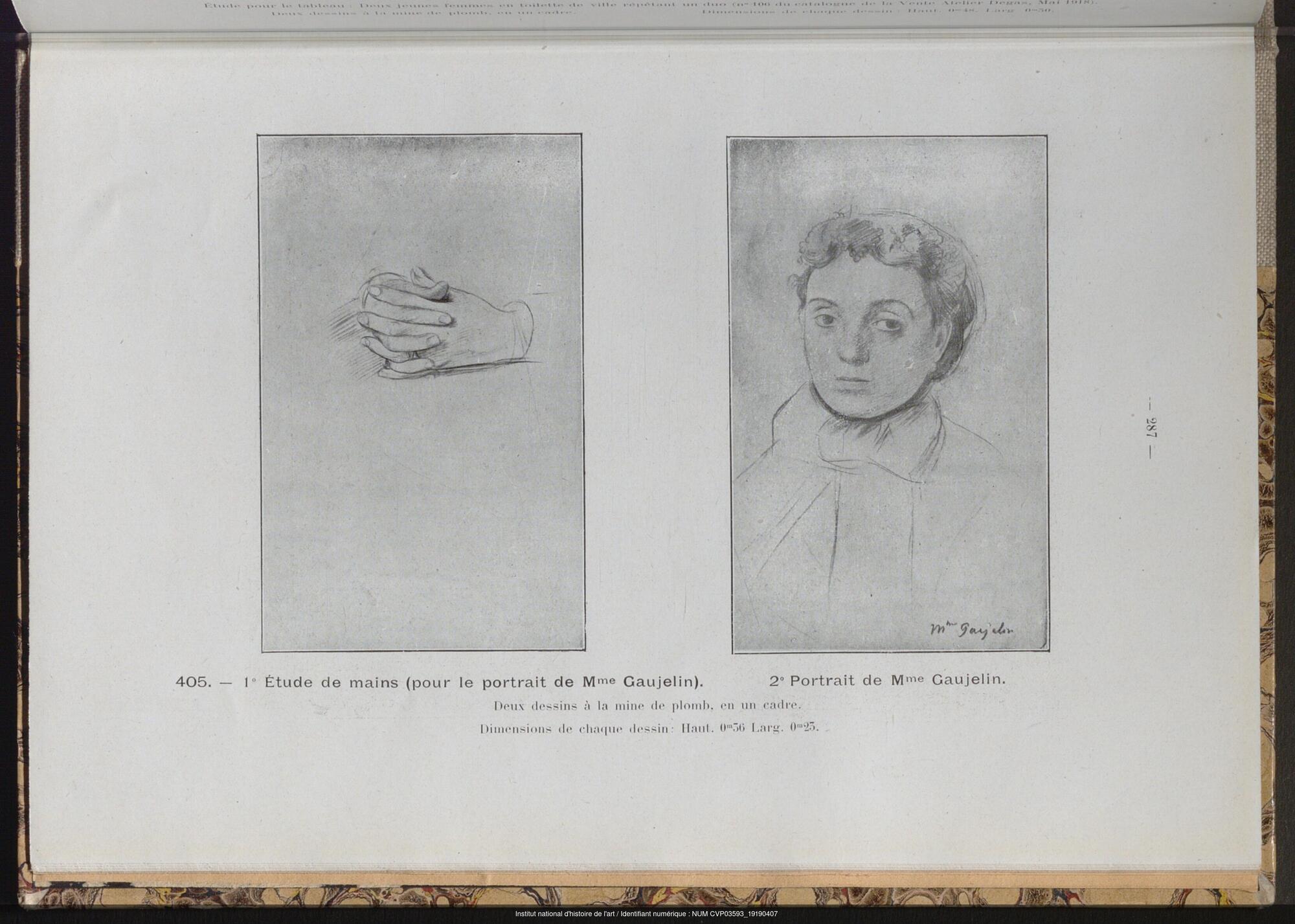

A clue finally arrived after Degas’ death, when the contents of his studio were sold at auction in 1919. There, a drawing clearly featuring the same sitter appeared—and helpfully, she was labeled as “Mme. Gaujelin.”

National Institute of Art History (public domain)

Georges Petit Galleries (active Paris, 1846–1933), Atelier Edgar Degas (3rd Vente), 1919, page 287, showing two studies for the portrait of Mme. Gaujelin

Gardner even corresponded with the French art gallery run by legendary Impressionist dealer Paul Durand-Ruel to track down the drawing. She wanted to see if it was still available for sale—sadly, it was not. Today, it is in a German museum collection.

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Edgar Degas (French, 1834–1917), Joséphine Gaujelin, before 1867. Chalk on paper, 36 x 22.7 cm (14 ⅛ x 9 in.)

The inscription of Mme Gaujelin identified the woman in the painting. She was Josephine Gaujelin, a dancer and actress who Degas depicted several times, including in another, sketchier oil painting.

Hamburger Kunsthalle / bpk Photo: Elke Walford

Edgar Degas (French, 1834–1917), Joséphine Gaujelin, 1867. Oil on panel, 35 x 26.5 cm (13 ¾ x 10 ½ in.)

So, how did Josephine Gaujelin’s identity get lost in the first place? She had commissioned Degas to make this portrait, but was not happy with the outcome. Mme. Gaujelin rejected the canvas, presumably because she did not consider it flattering. Degas, showing his standard flair for not caring what people thought, still sent the painting to the very public Paris Salon, albeit under a semi-anonymous title. While his client may not have been happy, the painter was. His friend, the Impressionist painter Berthe Morisot, wrote to her sister about the work:

[It is] a very pretty little portrait of a very ugly woman in black…it is very subtle and distinguished…Monsieur Degas seemed greatly pleased with his portrait.”

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Sean Dungan

The Yellow Room, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, 2010, showing Edgar Degas’ portrait

Gardner was also pleased with the portrait. Today, it holds pride of place as the centerpiece of the first wall visitors see in the Yellow Room.

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

The Misattributed Ballerina

Explore the Collection

Edgar Degas, A Ballerina, 1880

Explore the Collection

The Yellow Room