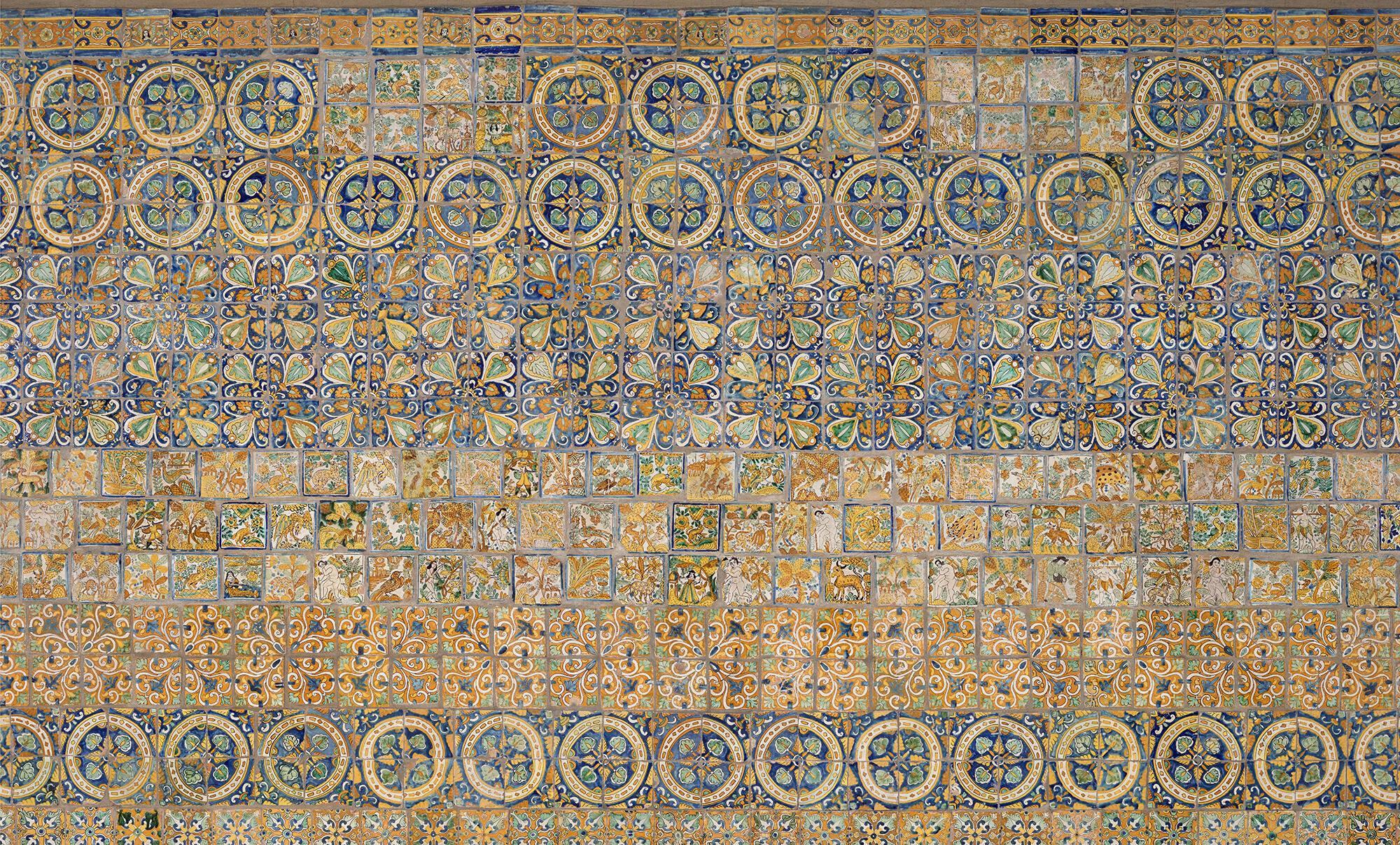

Some of the most beautiful and intriguing works in the collection are, perhaps unexpectedly, attached to the walls of one of the ground floor galleries: hundreds of brightly colored tiles decorated with flora, animals, figures, and geometric patterns.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. See them in the Spanish Cloister.

Mexican, Atlixco, Tiles from the Church of San Agustìn, Atlixco, Puebla, 17th century. Glazed terracotta

These tiles are examples of ceramics broadly known as Talavera, which are mainly produced in Puebla, a state in Mexico. After Spanish colonizers arrived in the region during the sixteenth century, these ceramic tiles started to emerge in Mexico. In the wake of the establishment of imperial rule, Spaniards familiar with the process of making tin-glazed earthenware—which is also made in the city of Talavera de la Reina in Spain—began to settle in Puebla.

Local craftspeople learned these methods and Talavera developed as a blend of indigenous Mexican imagery with Spanish methods and motifs. Many ceramic workshops were established to produce a range of products, and Puebla became famous for this type of earthenware. Buildings throughout the region are decorated with tiles like these; the ones here were probably made for the Church of San Agustìn in the city of Atlixco.

Despite a demonstrated interest in Mexican art and culture, Isabella only traveled there briefly in the 1880s—and her trip was only to the north of the country. Therefore, she learned a lot about the country, and acquired Mexican art, through her friends who traveled there more extensively.

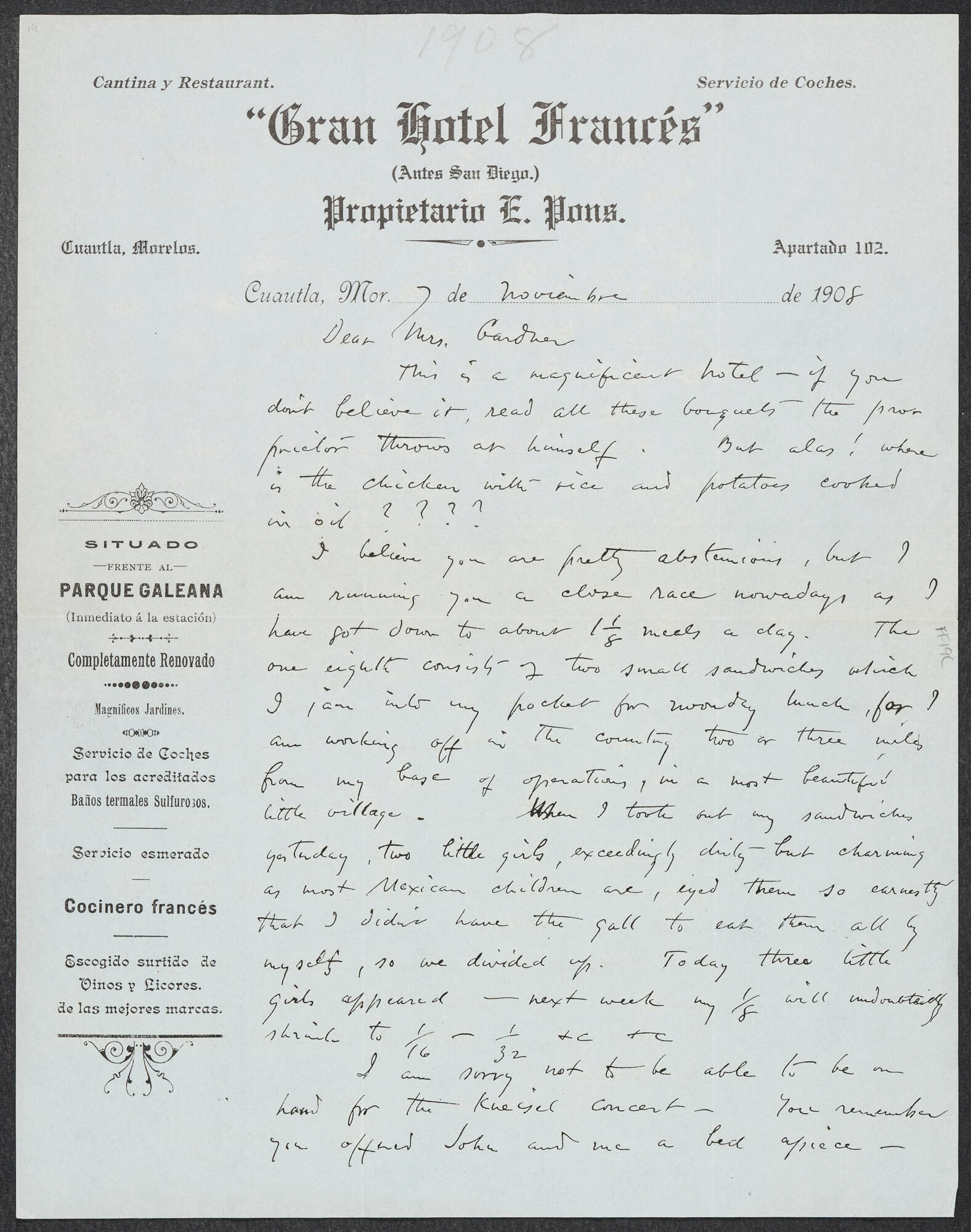

One of these friends was the artist Dodge MacKnight, who wrote to her regularly from his trips to Mexico. He was the one who discovered these tiles, possibly on a trip in the fall of 1908—a letter from him shows he was in Cuatala, about 100 kilometers (or a day’s travel) from Atlixco, and acted as her agent to purchase the tiles directly from the church. Once back in the United States, MacKnight wrote a letter providing Isabella a lively account of their acquisition, as well as a detailed accounting and estimates for shipping times and customs duties.

Dodge MacKnight (American, 1860–1950), Letter to Isabella Stewart Gardner from Gran Hotel Francés, Cuautla Morelos, Mexico, 7 November 1908, (page 1)

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.002817). Isabella displayed this letter in the Modern Painters and Sculptors Case in the Long Gallery.

She had clearly asked MacKnight to provide an account of how they had been arranged in the church, but he was unable to oblige. He wrote, “I made a dozen photographs but they did not succeed, for the church was too dark—but after all they would not have been of much use, for it will be much easier to make a new design and a better one. I am absolutely sure that the tiles have been taken up once and put back almost pell-mell.”

Isabella, therefore, seems to have created her own design once the tiles arrived at the Museum. She must have spent hours arranging the pattern of the nearly 2,000 pieces to frame the view into the Courtyard and flank John Singer Sargent’s El Jaleo (1882). The tiles line a gallery called the Spanish Cloister, which was a relatively late addition to the museum. It was constructed in 1914 after she demolished the Music Room that was part of the building’s original configuration.

The gallery presents a complex concept of “Spanish.” Objects range from the Talavera tiles—a product of the Spanish colonial enterprise in Mexico—to Islamic art apparently referencing Spain’s history under Islamic rule, and finally to Sargent’s image of a dancer performing flamenco, a dance rooted in Romani culture. Isabella presents many elements of the complex history of Spain all in one dense space, and the Talavera tiles are an integral part of the complicated story.

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

Isabella Stewart Gardner and Mexico

Shop at Gift at the Gardner

Mexican Tile Coasters

Explore the Museum

Spanish Cloister