Once the weather warms and pollinators appear, a parade of Hydrangeas transforms the Courtyard of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Colossal, cloudlike blooms sail over woody stems with saw-toothed leaves. The Hydrangeas in our living collection—hailing from Asia and North America—brighten the Courtyard garden from spring through fall.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Jenny Pore

Lacecap Hydrangea macrophylla in the Courtyard of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2022

The History of Hydrangeas

The botanical name for the genus Hydrangea was coined in the 18th century by Swedish biologist Carl Linnaeus from the ancient Greek words for water “hydor” and vessel “angeion.” While some say this was due to the plant’s love of water, others cite its seed pod’s resemblance to an amphora. [You can see an example of one of these ceramic jars with two handles in the Courtyard.] Because Hydrangea seeds are scarce, success in breeding new varieties is relatively recent.

Wild Hydrangeas have few showy flowers. Through breeding, cultivated varieties have been selected to flaunt impressive flower heads. Yet what appear as petals are actually not petals at all. They are sepals—sterile, modified leaves that protect the flower bud and are typically green. The brightly colored sepals of Hydrangea macrophylla are especially adept at showing off. Hydrangea sepals—like petals—have evolved to lure pollinators to the inconspicuous flowers that hide beneath them. Once a flower has been pollinated, the plant sheds its petals to conserve energy for the development of fruit and seed while sepals stay intact. This is why dried Hydrangeas can last for years.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Jenny Pore

Mophead Hydrangea macrophylla in the Courtyard of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2025

The Chemistry of Hydrangeas

The Gardner’s Hydrangea display begins in May with the Hydrangeas Courtyard installation, featuring the colorful mophead and lacecap varieties of Hydrangea macrophylla. Endemic to Japan, H. macrophylla—bigleaf hydrangea—boasts a kaleidoscope of changing colors from shades of pink to violet to deep blue, sometimes within the same inflorescence. This curious variation of pigments is created by the chemistry of the soil in which the plant grows. In acidic soil, the sepals appear blue. In alkaline—or basic—soil, the sepals are pink. Purple sepals indicate the plant’s soil pH is neutral. Aluminum is mobile in an acidic medium. The availability of aluminum ions is the key to unlocking the desired hue. Hydrangea growers can manipulate the color to their liking with the help of soil amendments.

Hydrangeas as Medicine

Many poisonous plants have been used medicinally throughout time. Hydrangeas contain cyanide—specifically cyanogenic glycosides—and can be toxic if ingested. The Cherokee people of what is now the Southern United States traditionally use the roots and rhizomes of the native Hydrangea quercifolia—oakleaf hydrangea—to treat conditions of the urinary tract. The plant’s diuretic properties show yet another connection of the Hydrangea to water.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Jenny Pore

Hydrangea paniculata in the Courtyard of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2022

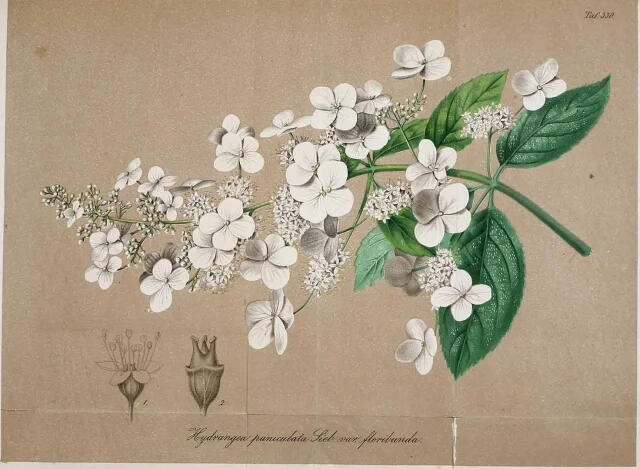

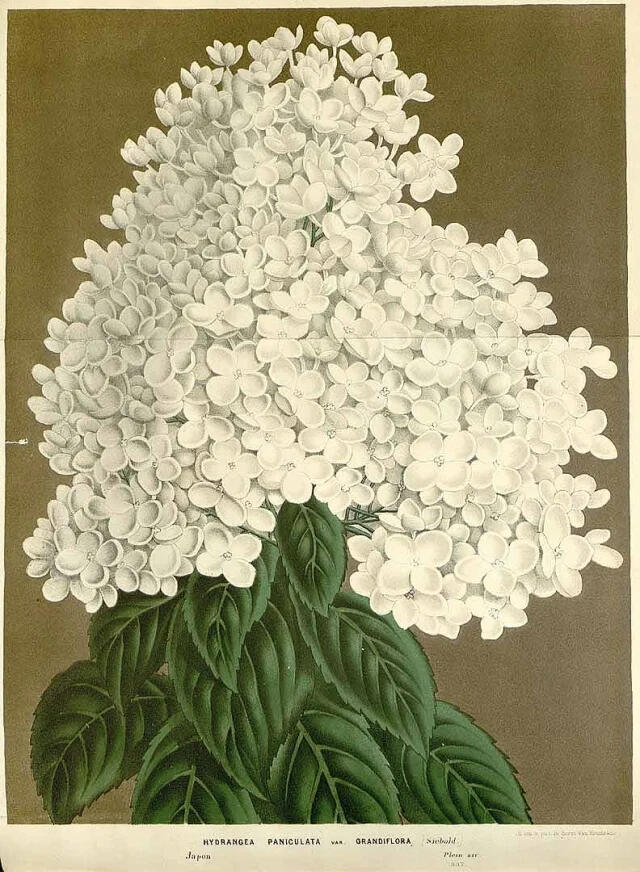

Hydrangea paniculata

Our Hydrangea parade continues in late summer with the ethereal beauty of Hydrangea paniculata—panicled hydrangea. Native to the forests and thickets of East Asia, H. paniculata boasts large, conical panicles that emerge pale green and gradually become white with age. The display of these shrubs threads through several of the Courtyard’s seasonal installations from Summer Blues through Bellflowers and the John Lowell Gardner Chrysanthemum installation in autumn. The diverse varieties of H. paniculata in the Gardner’s living collection include specimens of airy lacecaps and blooms that age to a soft pink as the day lengths dwindle.

Behind the Scenes

The Hydrangeas are cultivated at the Museum’s nursery. The shrubs’ pruning schedule depends on whether they produce flowers on old wood—the previous year’s growth—or new wood—the current year’s growth. Gardner Museum horticulturists prune species that bloom on old wood—like H. macrophylla—soon after their flowers fade to avoid removing next year’s buds. Species that bloom on new wood—like H. paniculata—are pruned in early spring.

Gardner horticulturalists carefully select the varieties and control dormancy to produce Hydrangea blooms in the Courtyard from spring through fall. We overwinter the Hydrangeas in cold frames and straw bale bunkers to allow the potted shrubs to experience dormancy while protecting them from the snow and ice of winter. The plants are pulled from dormancy in successions. The warmth of the greenhouses coaxes the plants to begin flowering ahead of schedule for New England’s climate.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Jenny Pore

Hydrangea paniculata with Amaranthus in the Gardner Museum’s outdoor nursery, 2023

The beauty of Hydrangeas is striking. In Isabella’s time, the Hydrangea represented boastfulness in the Victorian language of flowers. Isabella conceptualized and built a grand palace to share her collection of art. She collected pieces from around the globe and painstakingly curated installations with her own aesthetic. Although officially incorporated as the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in 1901, Isabella called her palace Fenway Court during her lifetime. Like the Hydrangea—whose colorful sepals both protect the humble flower and attract pollinators to it—Isabella’s palace of treasures did the same for her. Isabella ensconced her humility within the extravagant beauty she shared with the world.

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

Tracing the Tree Fern

Explore the Museum

Seasonal Courtyard Displays

Read More on the Blog

The Spirit of Violets