Most people tend to overlook decorative ironwork. It’s black, dusty, rusty, cold, hard, and so often used for defensive railings, or a door ring you just tug as you go through a door. But for a blacksmith, it’s another medium altogether. He (or she; I’ve attended a few classes too) stands in the dark forge so he can judge the exact colour of his iron bar while it heats. He feels the metal come alive as the bellows puff through the embers. It starts to droop and curl willingly into spirals; with a deft tap at exactly the right colour and temperature he can weld pieces together. If, for a split second, he glances away, his work of art starts to spit, snarl and spark until it vaporises to nothing. That’s why, if you are working with iron at a forge, the fire-breathing dragon form is just waiting in your hands.

In April 2025, Marian Campbell and I were asked to assess the decorative ironwork at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, aiming to provide more information about it. Accompanied by a team of curators and conservators, we examined more than 180 items over the course of a few days. This blog post shares some of our findings and excitements.

Consulting Curators, Jane Geddes, Professor Emerita, University of Aberdeen and Marian Campbell, former Senior Curator of Metalwork, Victoria and Albert Museum at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston in the Spring of 2025

Isabella had a particular love for iron candelabra and sconces. She chose to light almost every room with a medieval ambience of dim, flickering candles (now electric). Unfortunately, the dim light often conceals the many other iron furnishings. And dragons keep popping out. The oldest European dragons in the collection can be found on the large, French doors which lead into the Museum on its north side. One dragon lurks on the hasp, with a muzzle and pointed ears, and a second appears on the right end of the draw bar, with a ferocious fanged mouth.

This richly decorated style of door is found in the southern Pyrenees, where the supply of iron was plentiful and artists could afford to use the material lavishly. Doors in Coustouges have a dragon on the hasp, and an example in Prunet-et-Belpuig has the openwork door rings. The openwork design of the ring plates and the hatched decoration on the rings themselves are features which persist through the Middle Ages, so the date of the doors is likely 13th century. Demonstrating its early origin, the spiral design is also carved in stone in the Romanesque cloister of Elne, the early capital of Roussillon and there are many other examples in Catalonia, such as Mossot.

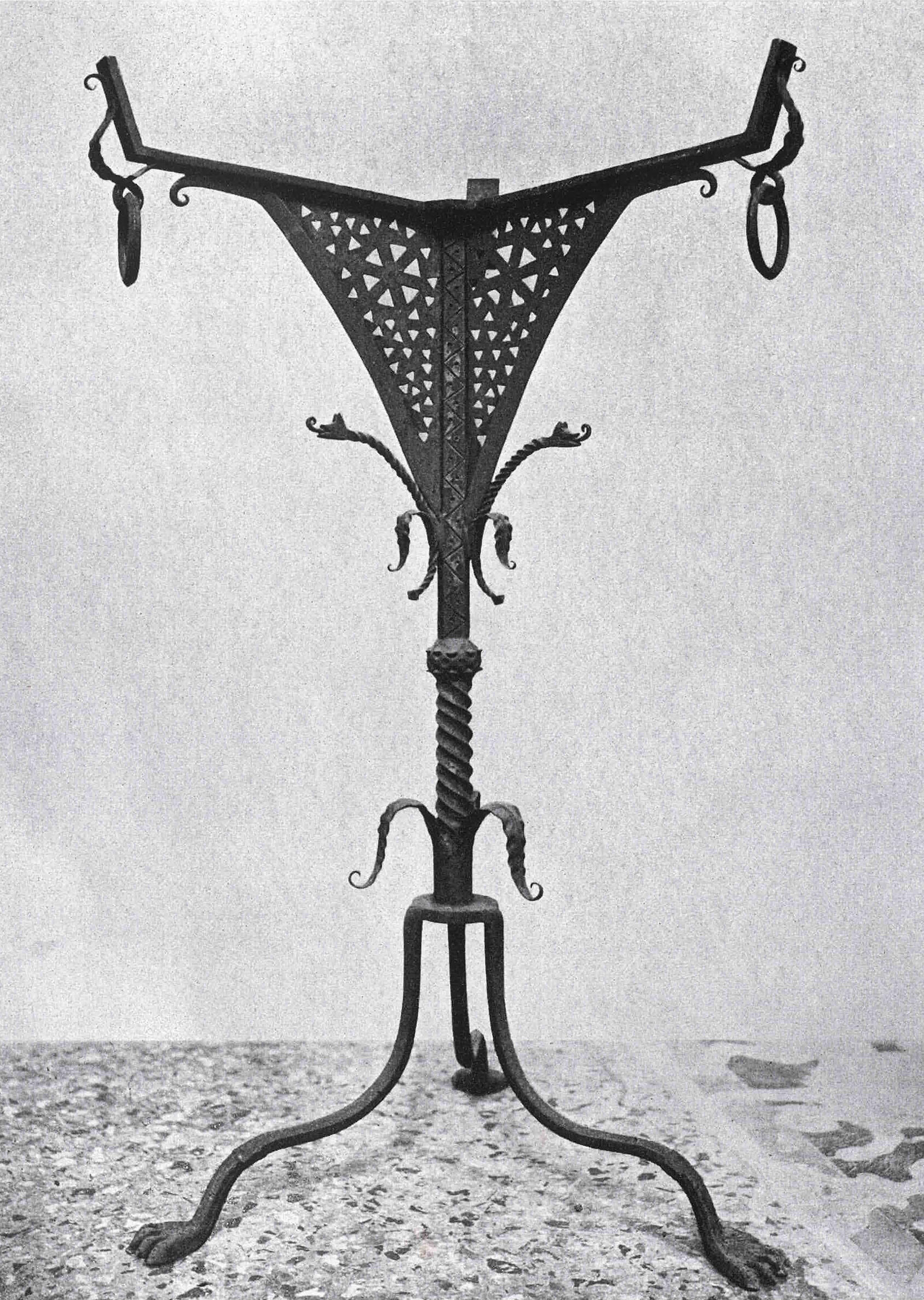

The large, iron tripod in the Raphael Room was bought in Florence but has no further information in the catalogue. Dragons spring out from its shaft to lick their noses while their heads with gaping jaws support the bowl. The spandrels (spaces above the arches) are filled with striking geometric cut patterns. These stands could hold a basin or brazier. The tripod has a close twin in Siena cathedral, with dragons on the shaft and stars and triangles in the spandrels but only plain supports for the basin. On the fresco painted by Domenico di Bartolo at Santa Maria della Scala, Siena, 1400–1441, you see the basin in use for washing the sick while the tripod in the Cleveland Museum supports a brazier tray. This suggests that Isabella’s tripod was made in the mid 15th century, at least from the region around Siena if not for the cathedral itself.

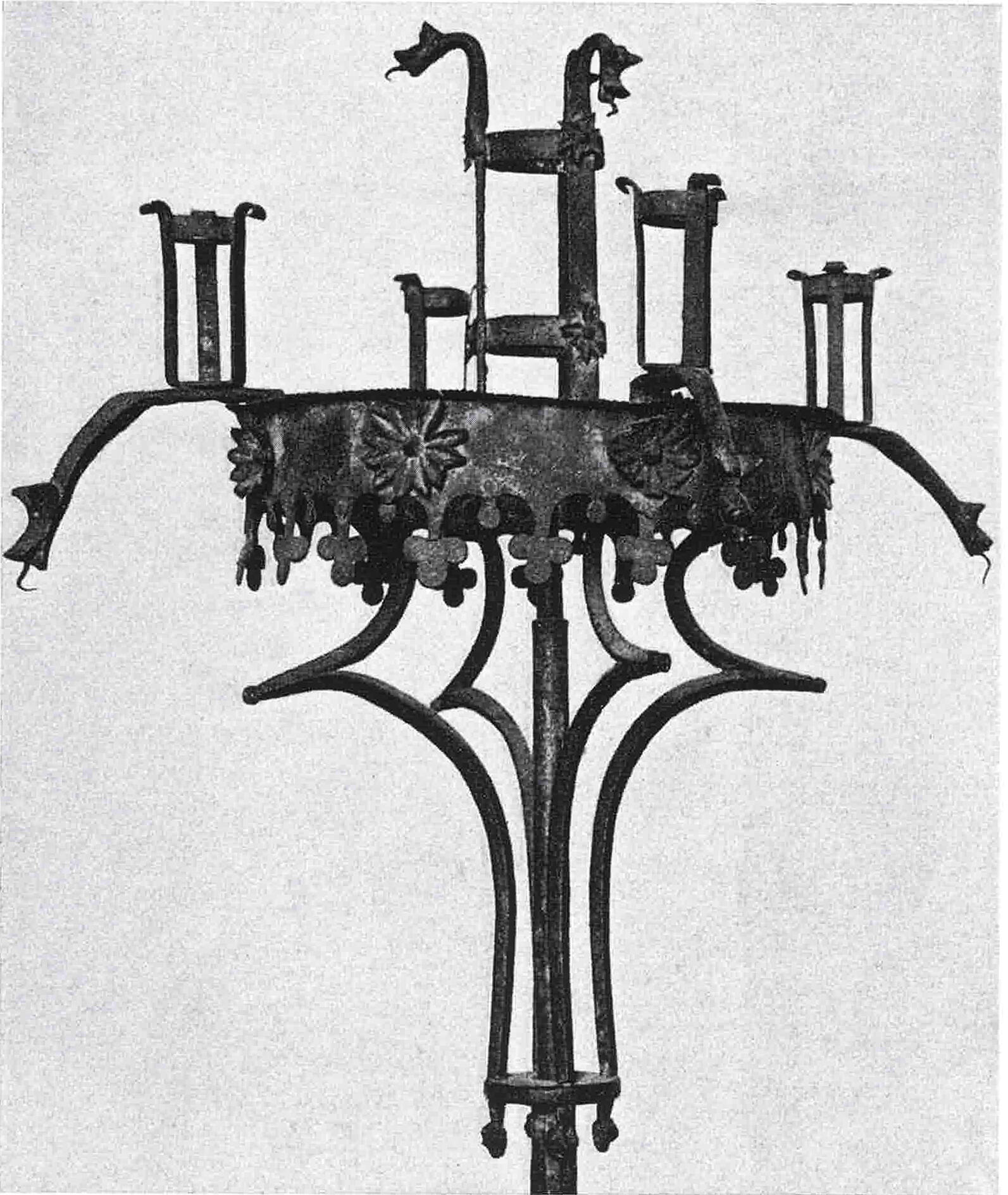

The candelabras in the Gothic Room are another puzzle. Not only are they vastly over-designed and in perfect condition, but they make a matching pair. They look like a fevered 19th-century fantasy. Their tripod feet are lion’s paws; the brackets which hold the wax drip pan are cut-out and chased leaves. From the pan, through a thicket of smaller leaves, spring angular brackets with tiny human faces on their cusps. From the ornate rim, slender aggressive dragons project horizontally and support candle spikes on their backs. Attached to the corona is an enigmatic shield, not yet explained. It shows a mitre and crozier, indicating a bishop, with three wheat ears above a grasshopper-like insect. This might be a coat of arms or a canting rebus (a visual pun), perhaps hinting at a name like ‘Bishop Cornhopper’ (in several possible languages). In spite of their eccentricity, the design crops up in a candelabrum at the Museo Sforzesco, Milan. This example is simpler but shares the corona form and sprouting dragons with candles on their backs. It also looks more weathered, perhaps being the 15th-century source for the motifs.

My last choice object was the most surprising and unexpected dragon appearance yet. In the Museum’s records, the object is described as a ‘candle holder, chimney and bracket’. Frankly, it looked rather like a tired flower pot holder, its circular iron links surrounding a glass vase. What caught my eye was what appeared to be a single cut-out leaf with curled lower lobes and a heart-shaped perforation in the centre, a type of leaf typical of ironwork in Saxony from about 1400–1700, found on gates and railings.

When the conservators teased the iron cage off the glass vase, one section looked very much like a horse bit, loosely wired at the top. After some examination and research, we came to the conclusion that it must be a 16th - 17th century German horse muzzle. One example from the Art Institute of Chicago is dated to 1674 and includes leaf forms similar to Isabella’s makeshift candle holder.

Art Institute of Chicago, George F. Harding Collection (1982.2200)

German, Horse Muzzle, 1674. Iron and leather

However, the true story behind this object did not become clear until months later. While capturing new photography of the muzzle, Collections Photographer Amanda Guerra noticed some incised lines in a cloud shape that were undeniably Japanese in style, along with Japanese characters inscribed on the bit. Viewing the object through this new lens, it became apparent that what we thought was a leaf was actually the head of a dragon! These suspicions were confirmed when two similar muzzles were identified at the Victoria & Albert Museum. These types of muzzles were used during the Edo period (about 1600–1868) to control grazing.

Isabella bought her ironwork from a variety of dealers in Italy, France and Spain, but mainly from her beloved Venice. With a bit of searching, many of her terse purchase documentation and catalogue entries come to life, placing the objects in a rich cultural context where great villas were being dismantled and their ancient furnishings scattered for sale, or where local artisans were still hand-crafting traditional ironwork designs for an eager market. This explains the eclectic quality of much of the ironwork on display in collections of the Gilded Age, including the varied ironwork found throughout the Gardner Museum.

FURTHER READING

M.Campbell, Decorative Ironwork, V&A Publications, London, 1997

H. R. d’Allemagne, Decorative Antique Ironwork, a pictorial treasury, Dover Publications, New York, 1968. Plates from 1924 French catalogue of Le Secq des Tournelles Museum, Rouen

L. Karlsson Medieval Ironwork in Sweden, 2 vols, KVHAA, Stockholm, 1988

A. Pedrini, Decorative Ironwork of Italy, Schiffer Publishing Ltd, Atglen, 2010. Originally published in 1929 as Ulrico Hoepli, Il Ferro Battuto Sbalzato E Cessellato Nell’Arte Italiana.

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

A Dragon Banner in the Courtyard

Read More on the Blog

Not Your Grandmother’s Silver Cabinet

Read More on the Blog

Keeping up with the Cobwebs