When Isabella Stewart Gardner needed to know whether there was a Titian on the market, or how much she ought to pay for a Rembrandt, or whether a Raphael was in fact a Raphael, one of the people she turned to most often was Bernard Berenson (1865–1959), an art critic, historian, and connoisseur. Berenson’s popular books on Italian painters, his definitive volumes on the drawings of the Florentine Renaissance, and his ability to help viewers in a gallery or church really see paintings as they hadn’t before, gave him a dramatic influence on American artistic taste during the Gilded Age. Although Berenson and Gardner were quite different from one another, their sensibilities were similar, and his talent for encouraging strong women was a part of their close and extremely fruitful working relationship.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

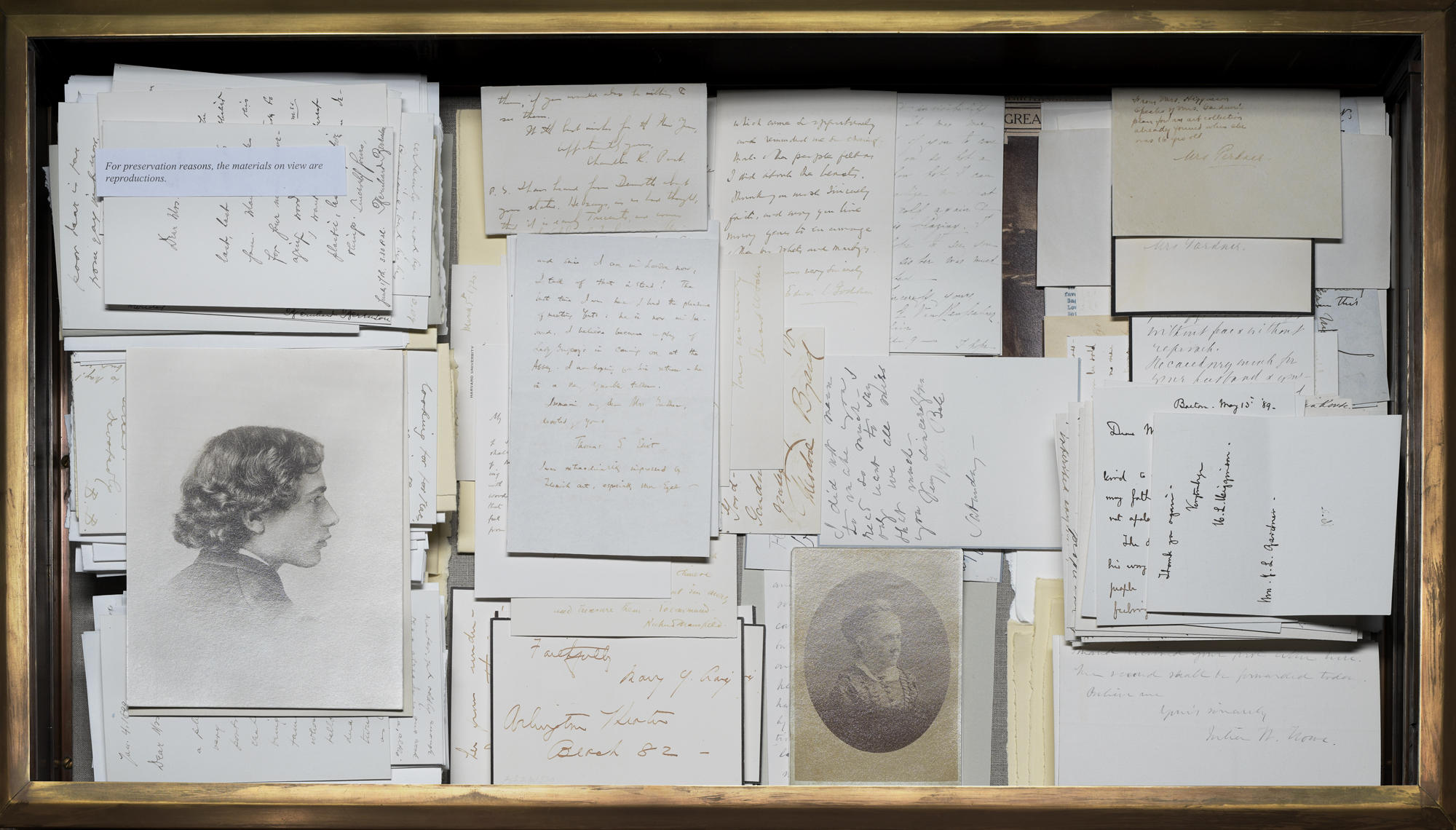

The Berenson Case in the Blue Room, 2019. Isabella dedicated a display case in the Museum to Bernard Berenson.

From the 1890s to the 1940s, Berenson’s research and authentications were one of the central pathways by which works from the prior five centuries left Europe and entered American museums. He was, however, generally a behind-the-scenes actor. He did not speak directly to J.P. Morgan or Andrew Mellon, but instead advised their dealers and advisors. But, he worked directly with Isabella Stewart Gardner during her most intense period of acquisition. In 1894, Berenson wrote to her, “How much do you want a Botticelli?” It was through him and the dealer Otto Gutekunst that she acquired her first Botticelli, The Story of Lucretia, and then the Titian Rape of Europa, Rembrandt’s Self-Portrait, a Raphael and many, many significant early Italian works. Unlike suggestions certain others made to Gardner, Berenson’s recommendations have generally held their value.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Sean Dungan

Botticelli’s Story of Lucretia in the Raphael Room, one of many works acquired by Isabella Stewart Gardner with the help of Bernard Berenson

A love of Italy and Italian arts ran through the Berenson-Gardner collaboration. They met, so the story was told, at a lecture on Dante by renowned art historian Charles Eliot Norton, when Berenson was a promising undergraduate at Harvard and running with a set of young aesthetes congenial to Gardner. But unlike Norton—who was quite anti-Semitic and did his best to block any possibility of Berenson finding a career in the arts—Gardner offered early financial support for Berenson to travel abroad and reconnected with him after he began publishing about art. At a time when there were no Jewish professors at Harvard, and museums did not hire Jewish curators, Gardner—though she was not without prejudice—was unusually willing to work with Jewish connoisseurs and dealers. Berenson’s view of art—that it could be both a sensual and a spiritual experience—was radical at the time and accorded with Gardner’s own convictions.

There were complex forces at play in their relationship—Berenson gave Gardner some of his best advice, but not in every case. He also made money off her and had a system of charging her to be her advisor, while also secretly getting a cut from Otto Gutekunst, the dealer she bought from. This was dishonest, even if the combined resulting fee was still less than many others might have charged. Several people, including Gutekunst, advised Berenson to be more straightforward. Learning of Berenson’s subterfuge upset Gardner, yet Berenson continued the practice, and Gardner never broke with him.

As I worked on my biography of Berenson [Bernard Berenson: A Life in the Picture Trade (2013)], certain puzzles kept recurring—why was secrecy so much a part of Berenson’s life? And why did these two understand each other so well, and not give up on one another? Was it despite, or because of, a tendency to hide?

A. Piatt Andrew Archive. Courtesy of Historic New England

Mary Berenson, A. Piatt Andrew, Isabella Stewart Gardner, and Bernard Berenson at A. Piatt Andrew’s home, Red Roof, in Gloucester, Massachusetts, in Red Roof Guestbook (1913–1930), 29 December 1913.

Berenson started his life as an impoverished immigrant from what is now Lithuania; he was shunned in institutions of power because he was Jewish, and much about his life was radical for the era. He lived with Mary Costelloe for years before they would marry. After marriage, they had an open relationship, and both had lovers. Berenson found secrecy necessary in certain parts of his life, and I think ended up creating secrecy even in situations where it wasn’t necessary. Secrecy may have meant something else to Isabella Stewart Gardner. Perhaps she got a thrill out of a slight illicitness in acquiring European treasures? Gardner’s letters to Berenson do contain injunctions (in her own italics) like:

“Please grab it. Don’t let anyone else have it, and if it really can’t be got out of Italy, take it away from him and have it put somewhere in the greatest secrecy for the present. Tell no one and let no one see it—please.”

Secrecy was certainly strategic in the cutthroat world of Old Master collecting, but Gardner may have been sympathetic to Berenson’s maneuverings both because they abetted her ambitions and because she understood a need to work in a solitary and private fashion as not everyone might. Natalie Dykstra’s recent biography of Gardner, Chasing Beauty, describes Gardner’s profound need for privacy to mourn her losses—the deaths of her son, Jackie, and her nephew, Joe, who took his own life. Furthermore, working in relative secrecy may have helped her to accomplish a highly unusual mission for a woman of her time: building her own museum.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (U18w77, U18w78.1-2, and U18w96)

Case of miniatures that Isabella Stewart Gardner displayed in the Little Salon. In the center is her son Jackie who died in infancy, in the bottom center, her nephew Joseph Peabody Gardner Jr who died by suicide at the age of 25, and on the right, her husband Jack Gardner, who predeceased her by 26 years.

Perhaps partly because they had been kept out of certain places of power and influence, Berenson and Gardner shared a kind of civic hope. They wanted to offer experiences of beauty and tranquility to people in Boston who did not have access to European sanctuaries. Berenson had grown up searching for such experiences and feeling the deprivation of being denied access. Gardner believed in the necessity of art and, in the religious and spiritual parts of her life, understood how people needed solace and inspiration in the wake of personal tragedy.

Photo: Sean Dungan

Courtyard, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

I believe Gardner and Berenson’s respective experiences with prejudice contributed to their understanding of one another. Perhaps this gave Gardner patience with Berenson’s secrecy and let him be sensitive to her intense need for privacy.

Gardner worked with people from a variety of backgrounds, never shying away from collaborating with those who were rumored to be queer. Throughout his life, Berenson fostered the projects of strong women. This collaborative capacity became a central component of my biography of him. For these women, their experiences of being treated “as a woman” met something in Berenson’s experience of being treated “as a Jew.” In each chapter of the biography, I presented Berenson in connection with another person. These pairings include Berenson and Gardner, another of Berenson and his dear friend, novelist Edith Wharton, and another of Berenson with his lover Belle Da Costa Greene, who was so crucial to the creation of the Morgan Library Collection, and is celebrated by that library for her accomplishments.

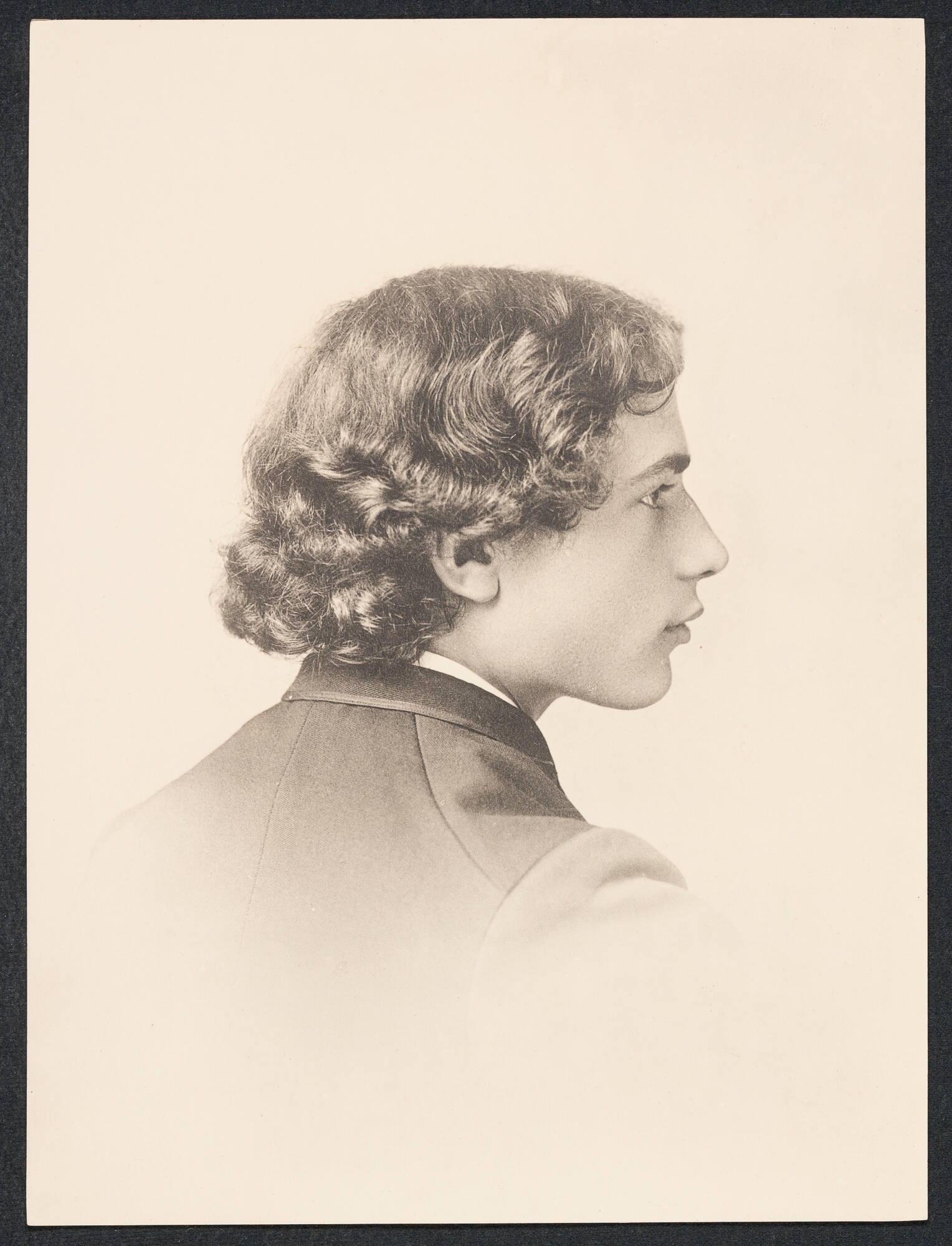

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.009224). Isabella displayed this photograph in the Berenson Case in the Blue Room.

Unidentified photographer, Bernard Berenson, Villa I Tatti, Fiesole, Italy, 1903. Gelatin silver print, 16.8 x 11.3 cm (6 5/8 x 4 7/16 in.)

In each of these relationships, there were thrills of similarity, sensibility, reciprocity, and of wild private ambition, that the individuals felt often had to be held apart and kept isolated and secret. There may have been relief in finding another person who understood the need to compartmentalize one’s emotional life. What Berenson was able to help Gardner achieve did come, I think, not only because they were appreciative of one another’s strengths, but also because they were able to comprehend, deeply, one another’s vulnerabilities.

***

Rachel Cohen is the author of Bernard Berenson: A Life in the Picture Trade, Austen Years: A Memoir in Five Novels, and A Chance Meeting: American Encounters, recently reissued by New York Review of Books Classics. Her writing about art and artists can be found at the Yale Review, The New Yorker, Apollo Magazine, and on instagram @rachelcohennotebook.

You May Also Like

Books at Gift at the Gardner

Bernard Berenson: A Life in the Picture Trade

Books at Gift at the Gardner

The Letters of Bernard Berenson and Isabella Stewart Gardner

Read More on the Blog

Isabella’s First Rembrandt