The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum has weathered its fair share of global adversity: it has “lived” through World War I, the 1918 flu pandemic, the Great Depression, and World War II. While the Museum continued to thrive as a cultural institution during these trying times, it also played an active role in helping artists—and artworks—survive the tumults of war and economic downturns.

Courtyard, 1934. This hand-colored photograph of the Courtyard in full bloom was taken during the depths of the Great Depression.

The best-known example of this work for a greater, national cause is former director George L. Stout’s service with the “Monuments Men” of the U.S. Army, who were deployed to Europe to locate and return artwork stolen by the Nazis. (And yes, there is a Hollywood film where a character based on Stout is played by George Clooney!) The most famous of the works the group recovered is the Ghent Altarpiece, painted by Jan Van Eyck (about 1390–1441) and his brother Hubert (about 1385–1426). They also recovered paintings by Dutch masters like Vermeer and Rembrandt, works by the Impressionists, and many other masterpieces.

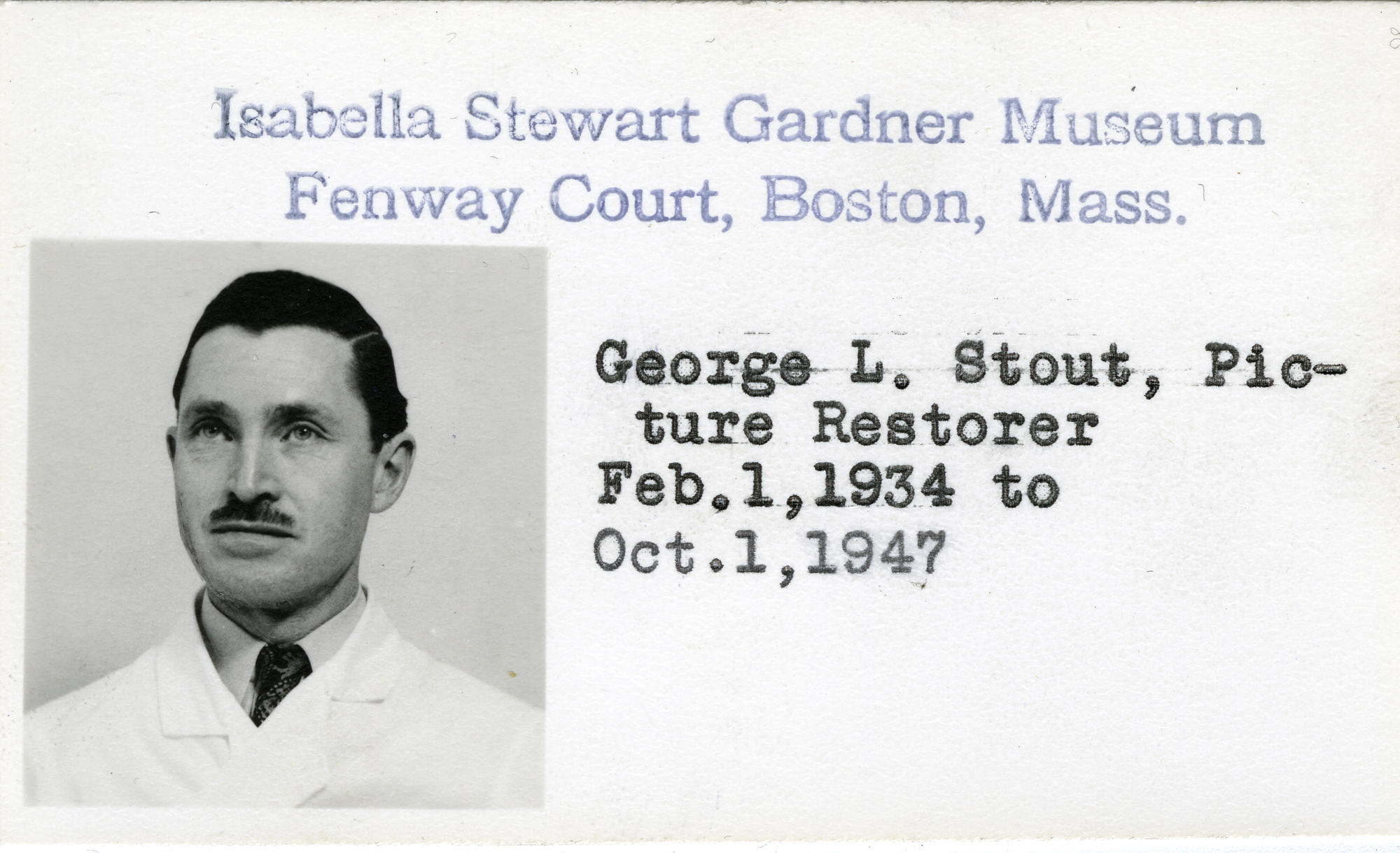

George Stout’s identification badge as Picture Restorer for the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 1934–1947

Years before Stout went to Europe to recover looted art, the Museum played another active role in a time of crisis: it served as the regional headquarters for the Federal Art Project in New England, which provided federal relief to artists during the Depression. As described at length in the Museum’s 1934 Annual Report, this national project—which supported many artists who would go on to become very famous, such as Jackson Pollock, Jacob Lawrence, and Lee Krasner—was designed to employ out-of-work artists and sometimes assign them to work on public art projects. The Museum’s Assistant Director, John Davis Hatch, became the Assistant Chairman of the program in New England, and the Museum itself became the registration site for local artists. As the report describes:

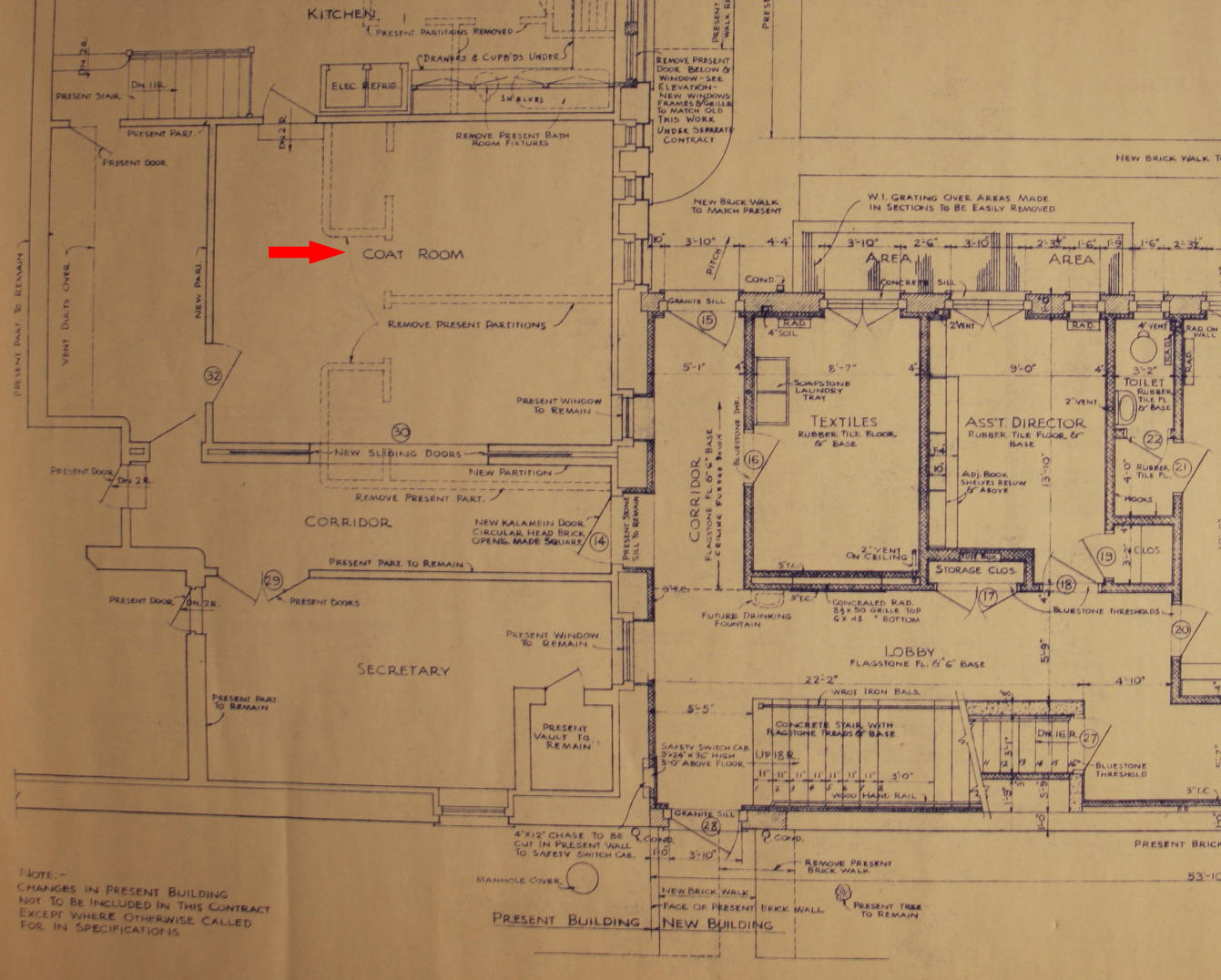

“The Museum classroom became the ‘Project’s’ office, and was equipped by the government with furniture and telephones; a force varying from four to eight worked there and in the…coatroom…In all, over four hundred applicants were interviewed. Two weeks later, thirty-seven artists were on the payrolls, and within another two weeks the regional quota of the hundred and fifty had been filled.”

One can even see the coatroom in question on blueprints for an old administrative annex of the Museum that has since been demolished.

Coolidge & Carlson Architects (active Boston, about 1900–1940), Extension to Administrative Offices, Fenway Court, 1931, showing the coat room

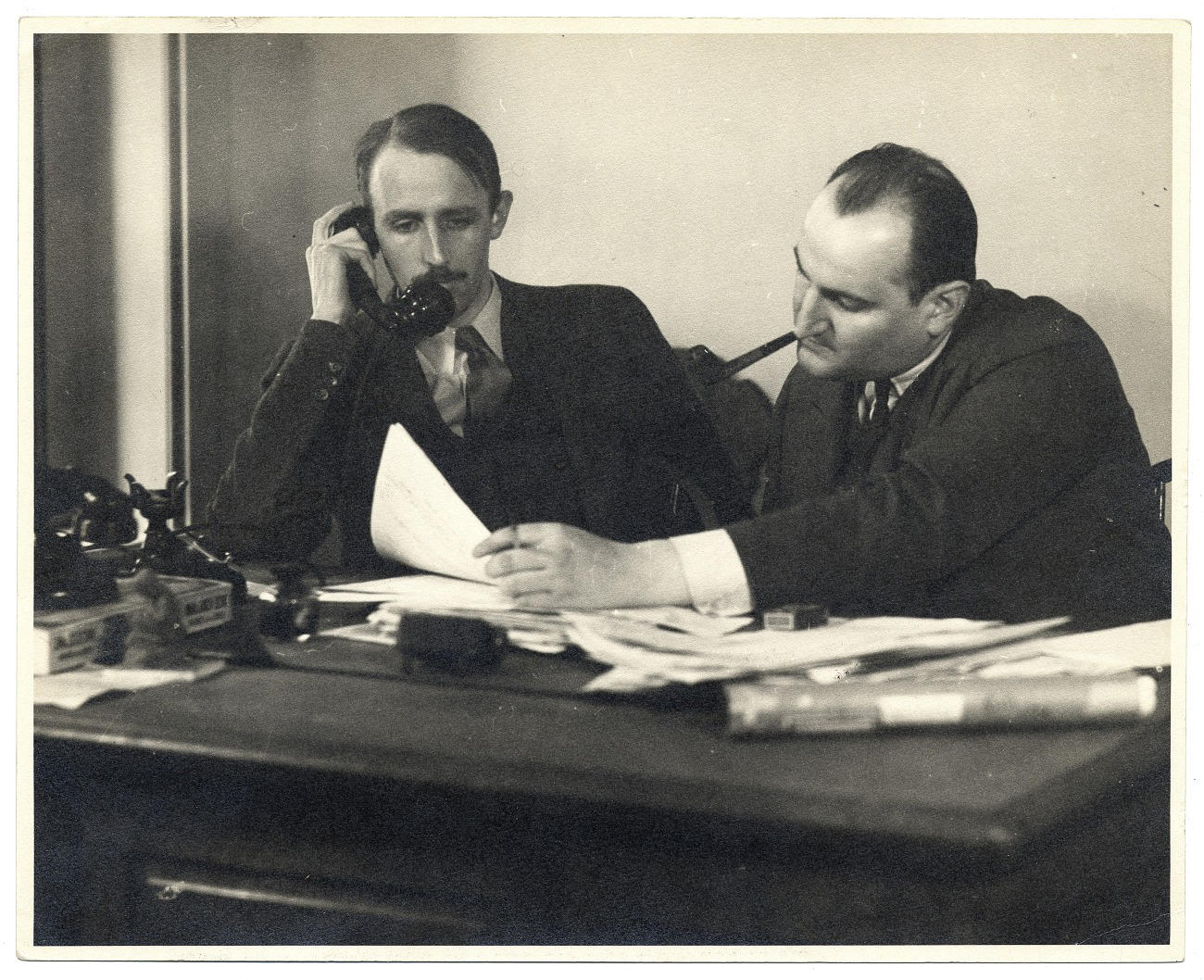

A photograph in the Archives of American Art shows Hatch and Francis Henry Taylor, then the director of the Worcester Art Museum, working on the project. Hatch also recorded an oral history about his experience.

John Davis Hatch and Francis Henry Taylor in the office of the Public Works of Art Project, February 1933

Photo: Miscellaneous photographs collection. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Digital ID: 2572

This history of support in times of need recently came full circle in 2019 when Hyman Bloom, one of the artists who received support from the New England chapter of the Federal Art Project, had his first (posthumous) solo show at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Without the federal support administered at the Gardner, Bloom’s career may have ended before it started—at age 21, he was one of the youngest recipients of aid.

Hyman Bloom (American, born in Lithuania, now Latvia, 1913–2009), Chandelier II, 1945. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Photo: © Stella Bloom Trust, Courtesy of the Hyman Bloom Estate, Photo by Jeffrey Nintzel

Though the Museum is well-known and thought of as a place frozen in time, it has a long history of rising to meet the present-day crisis. As then-director Morris Carter, wrote in the same 1934 report that described the Museum’s role in distributing Federal Aid: “the Museum should try to serve the general public in every way it can.” The Museum has stayed true to this standard in many ways over the years, including a continuing dedication to supporting artists with a residency program, hosting performances, and a wide-range of community-based initiatives. As of the initial publication of this post--in June 2020--the Museum is figuring out the ways it can respond to the coronavirus pandemic and its economic fallout, including by providing donations of personal protective equipment to Boston hospitals and donating flowers from our greenhouses to community gardens and organizations that provide meals and shelter for people that are food insecure or homeless. In 2020, like in 1934, the Gardner is seeking to serve the public in every way it can.