Mary Reid Kelley & Patrick Kelley: The Rape of Europa Gallery Guide

Intro | Essay | Transcript

As the title indicates, The Rape of Europa explores themes of sexual assault, incest, violence, and misogyny. It also includes explicit language and suggestive imagery.

Click here for additional resources

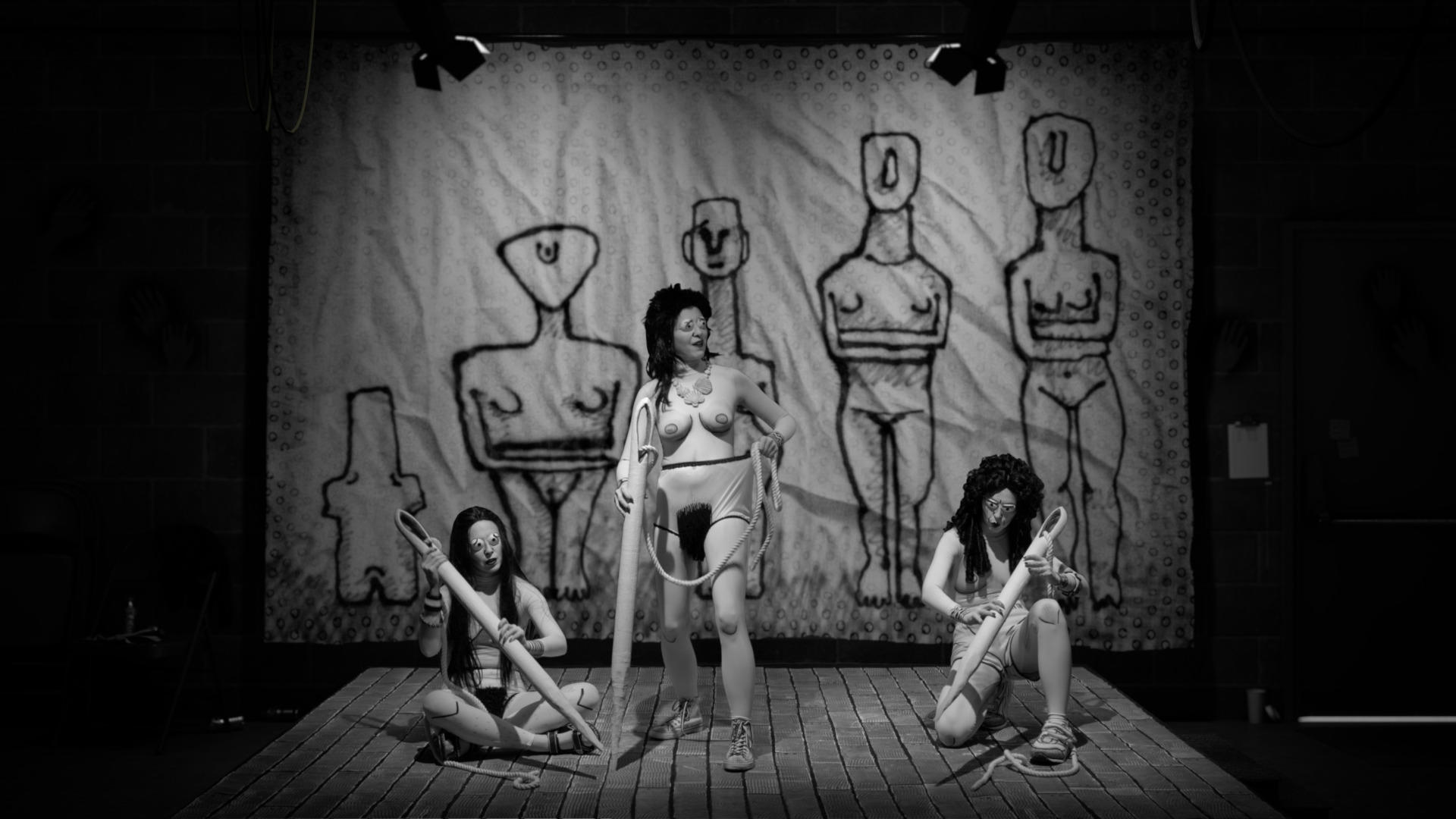

The Gardner Museum commissioned Artists-in-Residence Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley to respond to Titian’s Renaissance masterpiece The Rape of Europa, currently on view in the exhibition Titian: Women, Myth & Power on the second floor of the New Wing. The artists created a graphically stylized short film that combines painting and performance with Mary Reid Kelley’s distinctive satirical poetry. In the film, Mary plays a range of historical and mythical characters trapped between comic and tragic scenarios, layered into a densely detailed collage by Patrick. Their dilemmas, expressed through rhymes and puns, refer to longstanding social issues of rape, sexual assault, and incest, and resonate with the present-day #MeToo movement.

In Roman mythology, the character of Europa was abducted by Jupiter, the king of the gods, in the form of a bull. He then raped her, and the children she bore him became the founders of the European continent. In the film The Rape of Europa, a disgruntled and traumatized Europa speaks out against sexual violence and the degradation of women, using a form of wordplay called “Tom Swifties,” short phrases ending in a pun. Her angry rants are interwoven with theatrical skits that provide comic relief while addressing issues from incest to misogyny. The limerick, another poetic form often associated with bawdiness and sexual humor, is used in the skits to tell stories of the abuse and accomplishments of women in early history. This episodic, fable-like reenactment of stories from classical antiquity reminds us of the tales of the Roman poet Ovid, the principal inspiration for Titian’s mythological paintings.

This work and its sexually explicit language belong to a long tradition of feminist art that reclaims misogynist humor and themes in order to reveal and counter the objectification of women. By giving a voice to the character of Europa, Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley humanize and liberate her from the subservient and silent role she had long been forced to play in the ancient myth described by male poets and artists.

ESSAY

Mary Reid Kelly & Patrick Kelley's The Rape of Europa

By Jenni Sorkin, Associate Professor, History of Art and Architecture, University of California, Santa Barbara

Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley’s 2021 video The Rape of Europa is a biting, witty, and bawdy twenty-first-century response to the scene of sexual violence romanticized in Titian’s 1562 painting of the same title. The project, commissioned by the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, stands as a provocation to reconsider the sensationalized rape depicted in Titian’s masterwork, which is housed at the Museum.

In the video project, Europa is updated—reclaimed from her Greco-Roman mythological roots as a Phoenician princess and transformed into an entitled young professional coping with the aftermath of a violent sexual assault. The video is set in the Fenway Court of the Gardner Museum, meticulously remodeled by Patrick Kelley as a burned-out, dystopian warzone, a post-human landscape graffitied with the words “LET GO LET GO LET GO”—an urgent interior psychological plea, externalized. That message is twofold: it is aimed at Europa’s plight as the hapless victim of Jupiter, who in the myth has assumed the form of a bull, and also addresses her allegorical role in the entrenched colonial histories that she represents. The continent of Europe was named for her, and she embodies an entire history of European domination, conquests, and resource extraction—centuries of violence and plunder. It bears noting, too, that Europa’s depiction here, and throughout art history, as a white woman—although she is said to have come from the region of either Anatolia or Phoenicia (modern-day Turkey or Lebanon), and would thus have likely been dark skinned—has played a role in reinforcing a racially skewed Eurocentric picture of history and culture.

In the sixteenth century, Titian conceived of Europa as a body only, rather than a thinking subject. Patently sexist, his vision of Europa is emblematic of countless renderings of fully objectified women in Western art, endless reminders of women’s lack of political representation and social participation over the course of centuries.

Mary Reid Kelley’s verse turns all this on its head. It demonstrates the effectiveness of wit, and the ways in which humor can reframe power. If women laugh, even at themselves, they are not merely whores, virgins, or saints—those one-dimensional motifs that show up again and again in Western art and literature. There is profound agency in the levity that subversive comedy offers.

Using painstakingly hand-painted props, costumes, and animations, Mary and Patrick produce every aspect of their own videos. Mary writes the poetic scripts and is the primary performer: a character actor playing each role. Patrick is the director, animator, and cinematographer, and does the postproduction work.

The story of Europa’s plight unfolds at a fast clip through Mary’s raunchy limericks, sly quips, and feisty “Tom Swifties”—punning one-liners in which the protagonist’s utterances are matched to the verbs and adverbs that describe how she says them (e.g. “‘I’ve missed three periods,’ Europa recounted”). It is significant that the artists give their contemporary version of Europa agency: she is no longer a frightened, compliant odalisque, but a precocious speaking subject.

Yet she is also, unwittingly, something of a comic character, and her narrative is imbued with a deliberate slapstick tone. The style of the Mary and Patrick’s videos has strong roots in the physical comedy of early film, conveyed through exaggerated actions and heightened, scripted language. For example, The Rape of Europa opens with the protagonist’s backside to the viewer, visible through her shredded costume. When she turns around, the frank view of her genitalia, complete with a salon-groomed pubic area that hangs far below her body—is simultaneous horrifying and funny.

In counterpoint to the slapstick, Europa voices the soul-shattering physicality of her ordeal: she observes that the bleeding has maybe stopped, and hopes aloud that she isn’t pregnant. But her plaintive vocalization cannot stanch the flow of the psyche, or the psychosis that accompanies the aftermath of her rape: the trauma, the anxiety, the humiliation. As a misguided gesture of maturity, more than once she attempts to shrug off the brutalization impacting her—“‘I hate my own feelings,’ Europa mooed”—lamenting the indignity of having an emotional life, with its accompanying “moods.”

But Europa’s “mooing” also points out her degradation: she is, cow-like, a captive in a system of forced procreation. Her myth is really the story of the birth of two mighty twin brothers, who will grow up to be Minos, King of Crete, and Sarpedon, Lycian prince and heroic fighter (ultimately slain in the Trojan War). In this sense, Europa is a mere conduit, important only as sex object—a must-have virgin for Jupiter—and as the mother of two future leaders of Greece.

As such, our twenty-first-century Europa is stronger than she seems, even if she reveals her lack of resilience in other facets of life: she is, for example, a picky eater who is lactose-intolerant, avoids crustaceans, and won’t touch carbs. She passes judgment on just about everything around her—the “dumb kind of city” she has been dropped into (an allegorical one, to be sure), and the women who precede her in history, as detailed through Mary’s playful and ribald verse.

Interspersed throughout Europa’s narrative are limericks offering miniature historical sketches. They are presented by a rotating cast of raucous performers who argue the case of women as a social force in humanist terms: as innovators in agricultural, artistic, and technological innovation. These vivid lines propose a matrilineal mythology: a proto-feminist folkloric geography verbally mapped by limericks set across the Middle East, Europe, and Africa, antidotes to the white-male-centered narratives of Greco-Roman mythology from which so much of Western artistic production draws. Among other things, the limericks attribute to women artisans two Neolithic milestones: the stone quern, an early device for milling grain into flour, and the Venus of Willendorf, a powerful female votive, long thought to be a fertility symbol. They credit women with the invention of needles, beer, and yogurt, as well as fundamental social structures such as mutuality and kinship networks.

Dramatizing their outrage, rebellion, and vulgarity, Mary’s verse celebrates women who flout social conventions, who seek control over their own bodies and desires, and who fight back when misunderstood or unjustly treated. The video recalls feminist protest actions and video art of the 1970s, a genre that utilized varying degrees of parody and humor, social critique, and performance art, sometimes excavating art history, to make pointed appraisals across a range of social issues, including sexual inequities and abuse. The work of German artist Ulrike Rosenbach comes to mind, for example: in a 1975–76 video she reimagined Botticelli’s Birth of Venus as a spectral image, with her own body replacing that of the goddess. In 1977 artists Suzanne Lacy and Leslie Labowitz took on the subject of rape with Three Weeks in May, a series of actions and performances protesting the lack of protections and credibility afforded to victims of sexual violence.

According to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network, the largest anti-sexual-violence advocacy group in the United States, someone in this country is a victim of sexual violence every sixty-eight seconds—the majority of victims are young, like Europa. And of course this accounts only for those who report the violence: innumerable incidents are never tallied.

Still, nearly five hundred years after the Enlightenment popularized secular thinking and rationality in Titian’s Europe, our country is encountering its own enlightenment in the form of the #MeToo movement, a sociopolitical reckoning with the longstanding misogyny, violence, and oppressions aimed at women in contemporary culture. Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley’s The Rape of Europa engages wryly and powerfully with this moment of reckoning.

TRANSCRIPT

Explore the full exhibition

The lead sponsors of Titian: Women, Myth & Power are:

Amy and David Abrams

The Richard C. von Hess Foundation

The presenting corporate sponsor is:

This exhibition is supported by the Robert Lehman Foundation, Fredericka and Howard Stevenson, and an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities. Additional support is provided by an endowment grant from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities. The Museum receives operating support from the Massachusetts Cultural Council. Media Sponsor: The Boston Globe.