Drawing the Curtain: Maurice Sendak’s Designs for Opera and Ballet

Gallery Guide

Maurice Sendak (1928–2012) is best known as the beloved author and illustrator of iconic children’s books such as Where the Wild Things Are (1963) and In the Night Kitchen (1970). He had been working in children’s literature for two decades when he was asked to design costumes and sets for a new production of Mozart’s The Magic Flute. A lifelong opera fan, Sendak leapt at the opportunity and said of his initiation into the world of stage design, “Fifty is a good time to either change careers or have a nervous breakdown.” Full of rich references to Old Master artworks, Sendak’s playful designs were anchored in his fascination with collections of historic art like the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Like Isabella Stewart Gardner herself, whose passion for music equaled her love of visual art, Sendak embraced the multidisciplinary nature of the museum, where he lectured in 1991. We invite you to be enchanted by this lesser-known but no less impressive area of Maurice Sendak’s prolific career.

This online gallery guide features only a selection of the more than one hundred preparatory drawings and a selection of costumes and sets on view that Sendak created for four stage productions: The Magic Flute, Where the Wild Things Are, The Love for Three Oranges, and The Nutcracker. As with all of his work, these designs transported people to whimsical, faraway, and occasionally scary places. Alongside fellow book artists–Jean Bourdichon and Oliver Jeffers, featured in the Fenway Gallery and the Museum’s Anne H. Fitzpatrick Façade–Sendak invites us to imagine new worlds.

Sendak wearing the Nutcracker costume on the set of Nutcracker, The Motion Picture, 1986.

MLM92100, © Maurice Sendak Foundation, The Morgan Library & Museum, Bequest of Maurice Sendak, 2013, 2013.107:345

Object Description

This vertical color photograph shows Maurice Sendak from the knees up, facing us from what appears to be a stage. He has medium-light skin, glasses with dark oval frames, brown hair, a moustache, and a trim beard flecked with gray. He is wearing a loose white shirt gathered at the wrists and with a ruffle under the chin, a reddish-brown sleeveless vest with a collar and gold trim at the edges and in three horizontal arrows across the front, and reddish-brown tights. Sendak’s arm to our right is bent, and he holds a large costume headpiece on his shoulder, perpendicular to his own head and parallel to the floor. The costume headpiece has a reddish-brown crown, large bulging white eyes, bright white teeth, a black moustache, a beard, and large ears. Sendak’s other arm, to our left, hangs by his side. At his back there is a dark vertical area. On either side of him are brown curtains and some indistinct items.

Maurice Sendak never considered the life of a child to be carefree. He was born in 1928 and raised in Brooklyn by Polish Jewish immigrants, and much of his extended family died in the Holocaust. Like many in their Yiddish-speaking community, his parents believed that children should not be shielded from the darker parts of the world.

As an adult, Sendak spoke at length about his own physical and emotional struggles during his youth. He was a sickly kid who often had to remain in bed; drawing served as an escape. He said, “I couldn’t play stoopball terrific, I couldn’t skate great. I stayed home and drew pictures. You know what they all thought of me: sissy Maurice Sendak…”

This invocation of the term “sissy” alludes to Sendak’s recognition from a young age that he was gay. Coming of age during World War II and the homophobic political persecutions of the McCarthy era, he had an early awareness of his multifaceted identity as a Jewish, gay, and chronically ill person. This experience formed his mission as a children’s author and illustrator: providing young readers with stories to help them negotiate their own complicated emotions as they grow up in an inevitably flawed world. Sendak brought this complex sensibility about identity, childhood, and the role of fantastical stories to his stage designs.

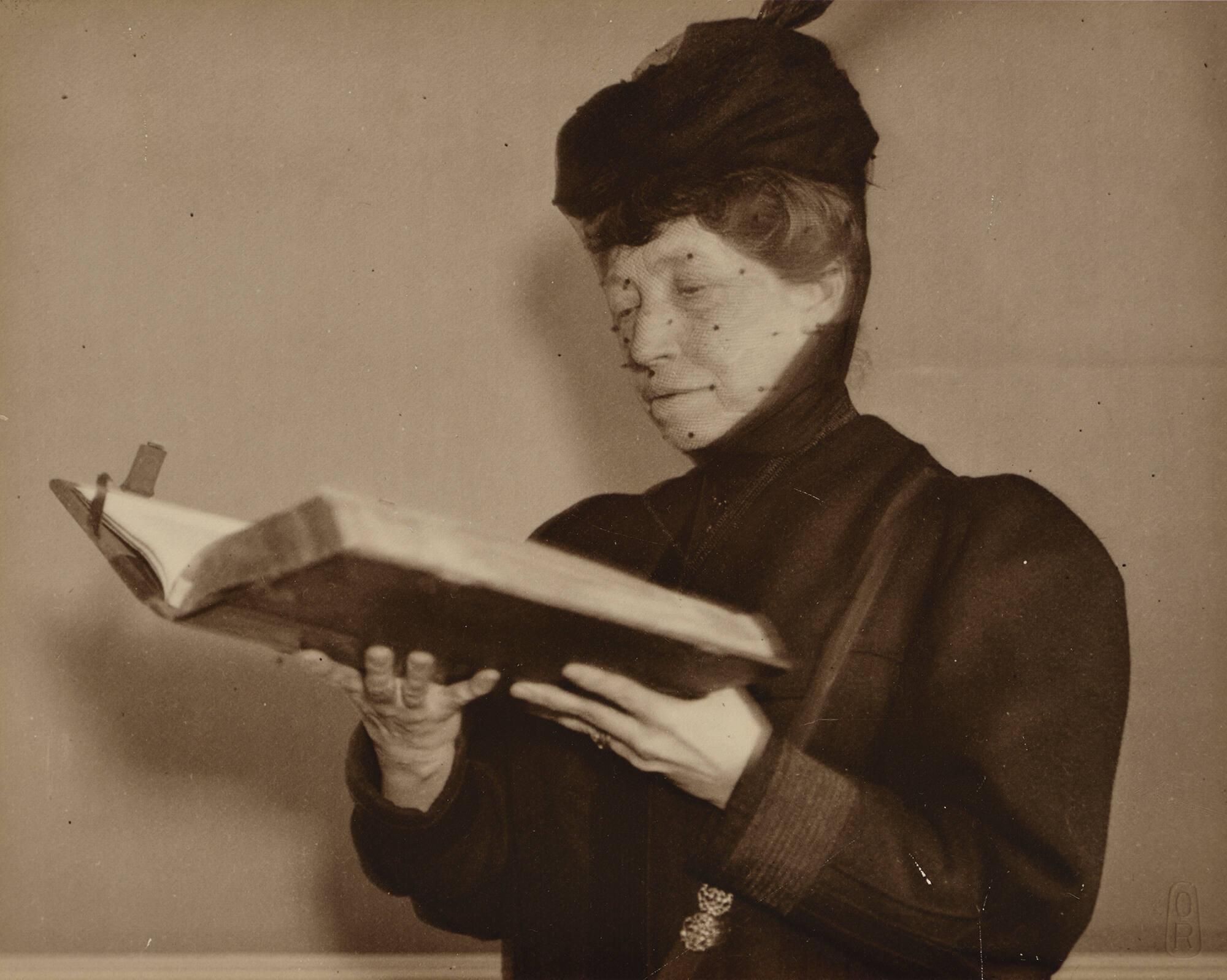

Otto Rosenheim (German, 1871-1955)

Isabella Stewart Gardner, 1906

Gelatin silver print

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Object Description

This portrait photograph of Isabella Stewart Gardner shows her from the waist up holding a large unclasped book open in her two hands which are splayed underneath to hold the heavy volume close up in front of her. She is dressed in a dark woolen coat with just one ribbed cuff visible; underneath she wears a dark dress with a high collar. A dark leather strap decorated with two metallic buttons crosses over her body from her left shoulder and probably is attached to a purse. She also wears a small dark hat whose dotted veil is tight over her face. Mrs. Gardner is turned a quarter way to her right with her face tilted down, reading the book. Her lips are ever so slightly open and she appears to be studying the text. The bottom of the photograph is inscribed R O in an oval - photographer, Otto Rosenheim's initials.

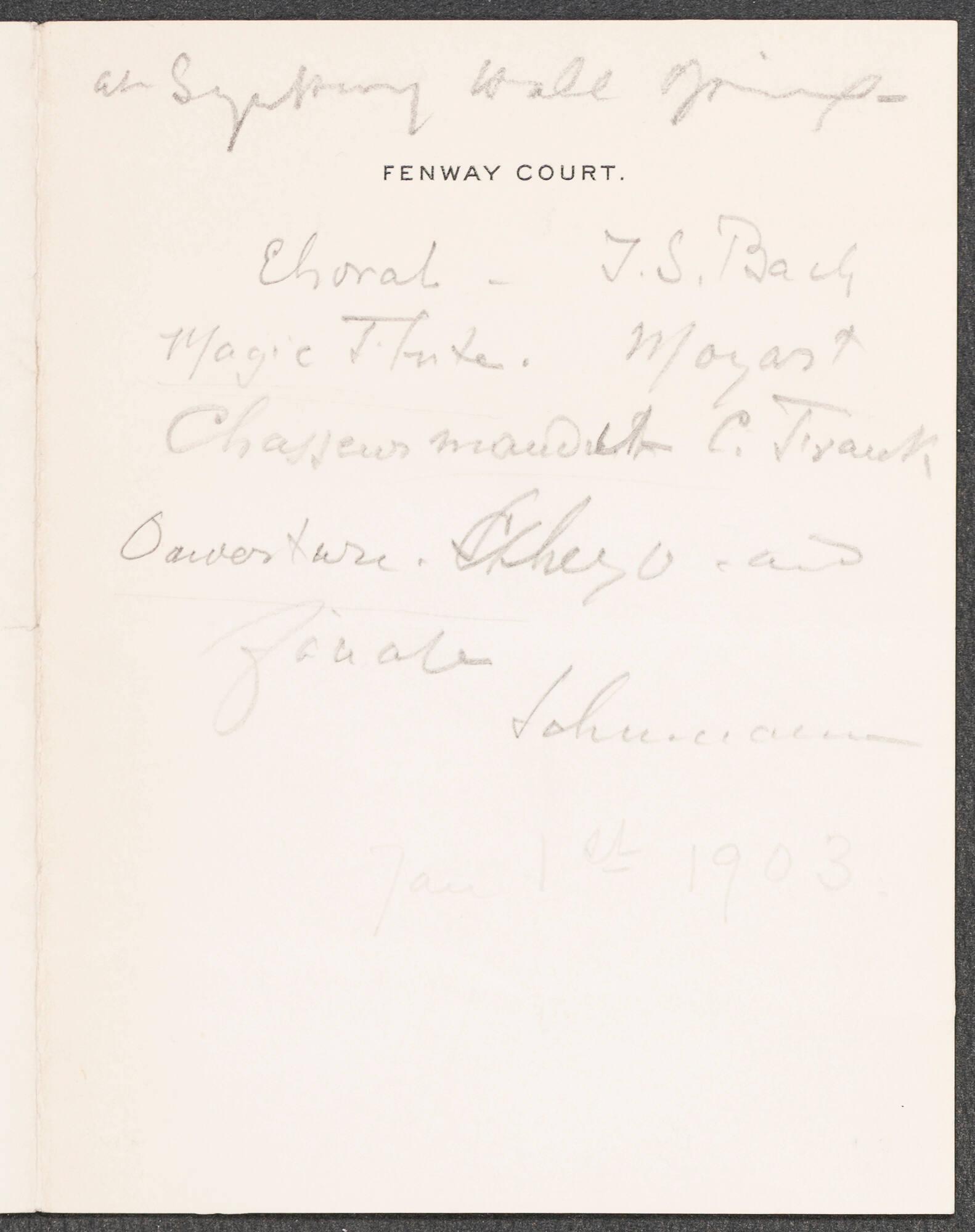

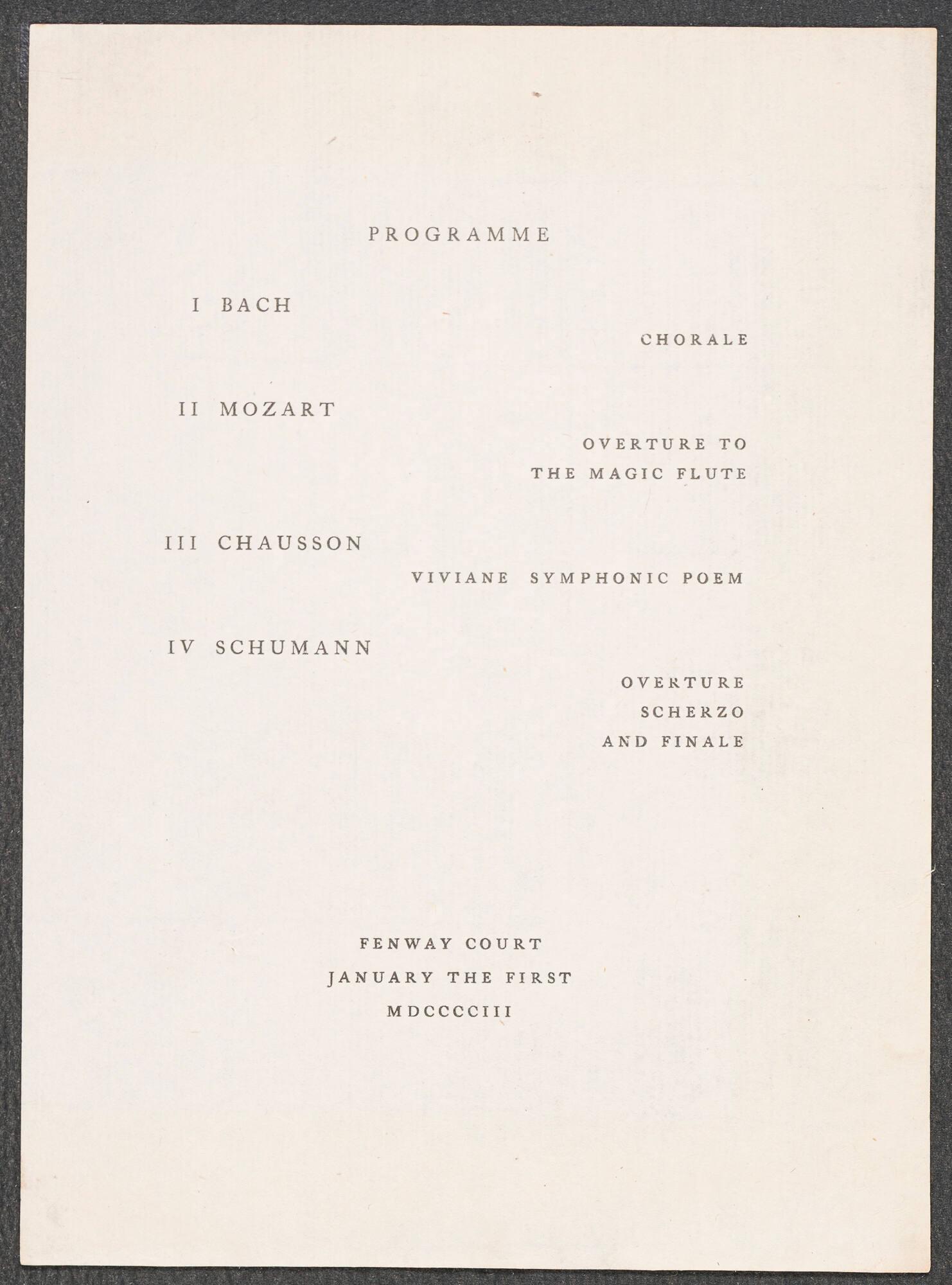

Sendak and Gardner: A Shared Love for Music

Maurice Sendak and Isabella Stewart Gardner had more in common than one might think. Both native New Yorkers, they shared a love for music and its capacity to inspire creativity and complement the visual arts, as well as a passion for conjuring immersive environments.

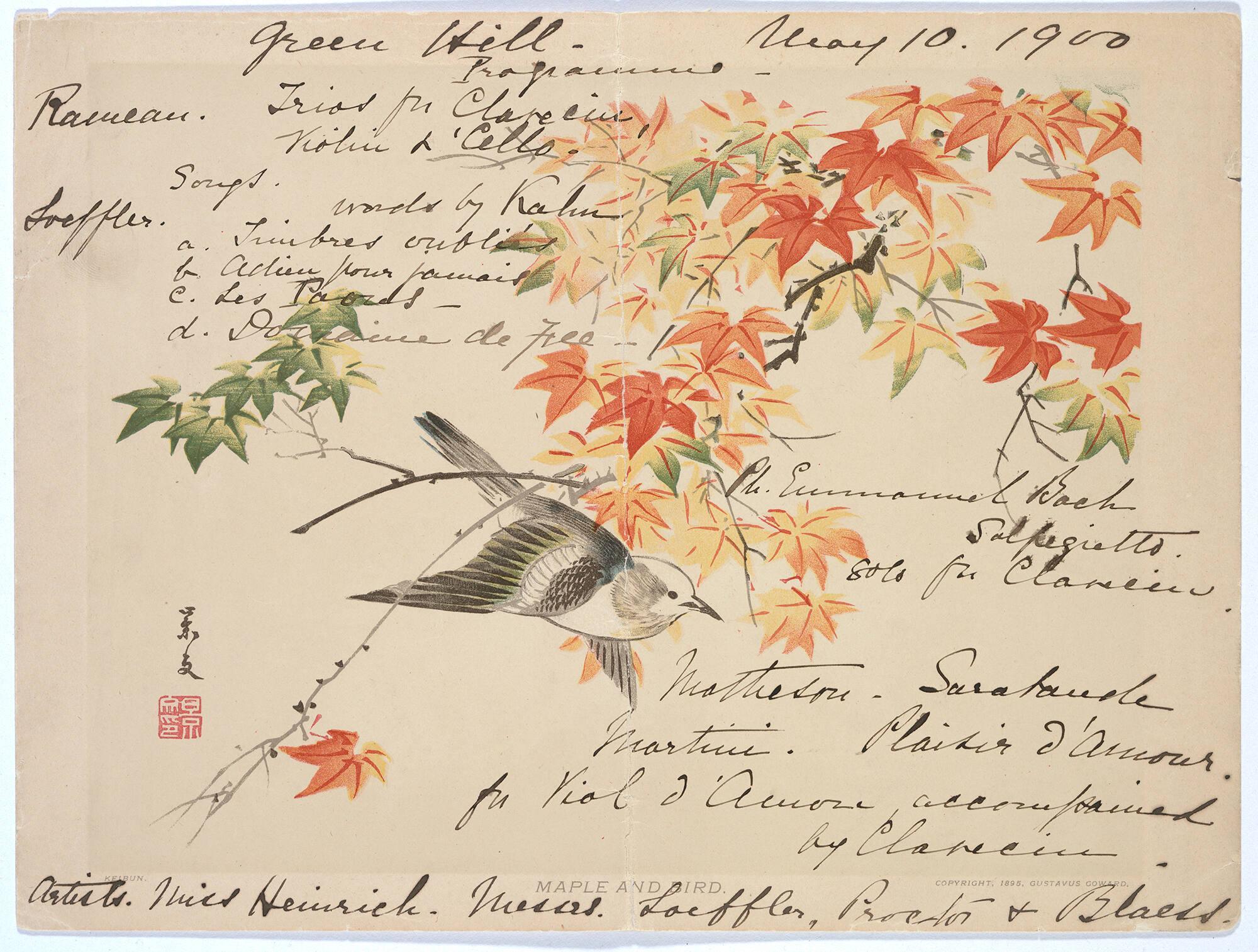

The Gardner Museum’s opening night in 1903 featured performances by the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Gardner’s carefully selected program included the overture to Mozart’s fantastical opera The Magic Flute—a fitting accompaniment to the wondrous setting she had created. The opening concert set what has since become a century-old tradition of the museum serving as a vibrant venue for the performance of live music.

Mozart’s opera—and classical music and opera more generally—held a similar pride of place for Sendak. His passion for classical music started in adolescence, and he said in a 1966 interview: “I can hardly live without music … [and] I do most of my work to music.… All composers have different colors, as all artists do, and I kind of pick up the right color from either Haydn or Mozart or Wagner while I’m working.” Some of Sendak’s works directly translated music into visual art, such as his “fantasy sketches”—spontaneous sequential narratives he drew while listening to a piece of music.

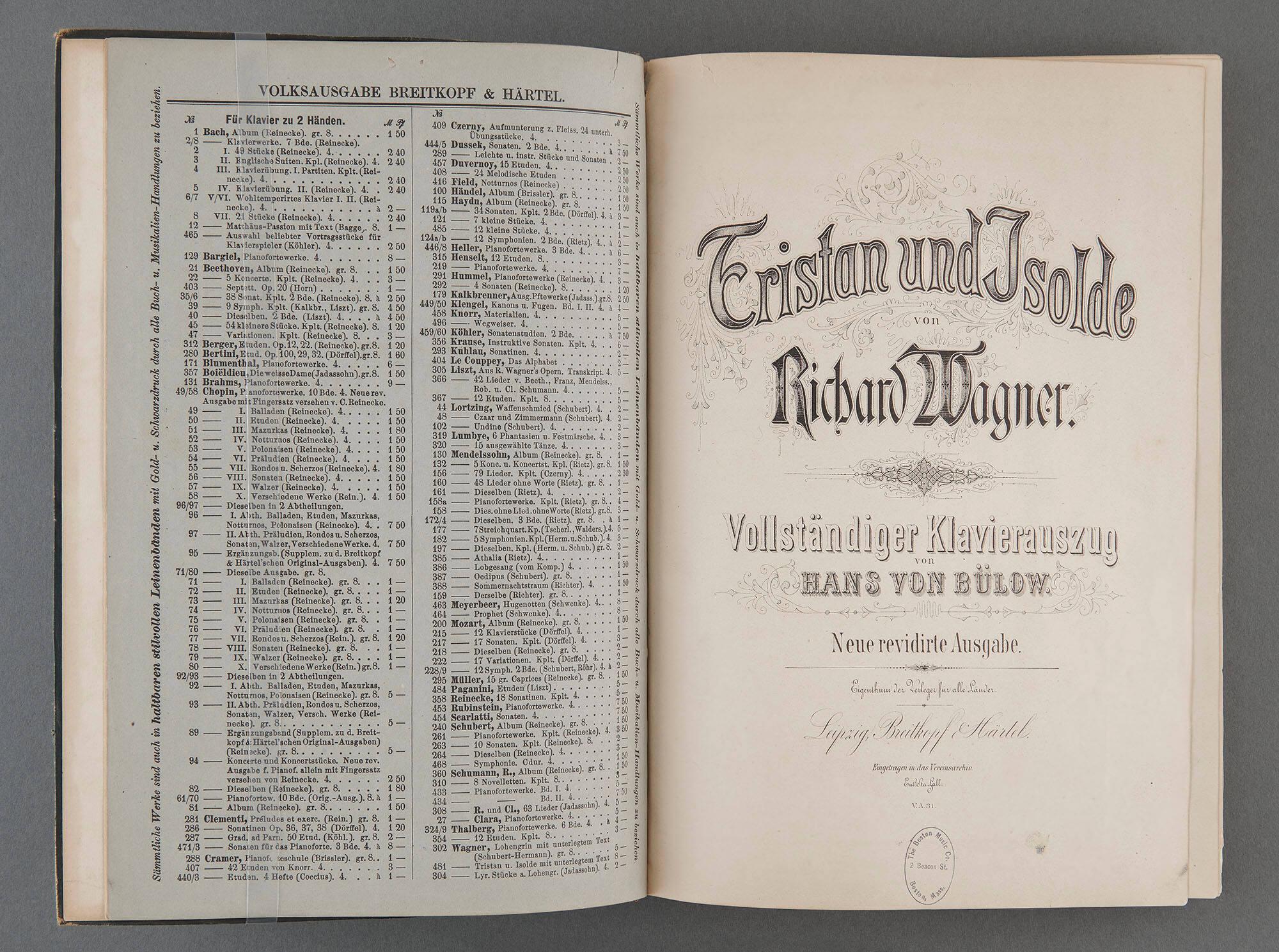

Isabella Stewart Gardner had a passion for opera. She collected scores for her favorite operas to study the intricacies of music and plot. Gardner used this vocal score from Richard Wagner’s opera Tristan und Isolde for 27 years, taking it with her to performances from Boston to Bayreuth, Germany. It contains mementos from many performances that she saw – autographs from performers, handwritten cast listings, and a note from renowned conductor Karl Muck, who was the musical director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra from 1906 to 1918.

Opera is an art form that unites music, narrative, orchestration, singing, acting, set design, costumes, and even the architecture of the theater into a single transcendent work of art. It’s no wonder that the integrated artistic experience of opera struck a chord with Isabella Stewart Gardner, who herself created a Museum that seamlessly fuses art, architecture, horticulture, and music to create an immersive artistic world.

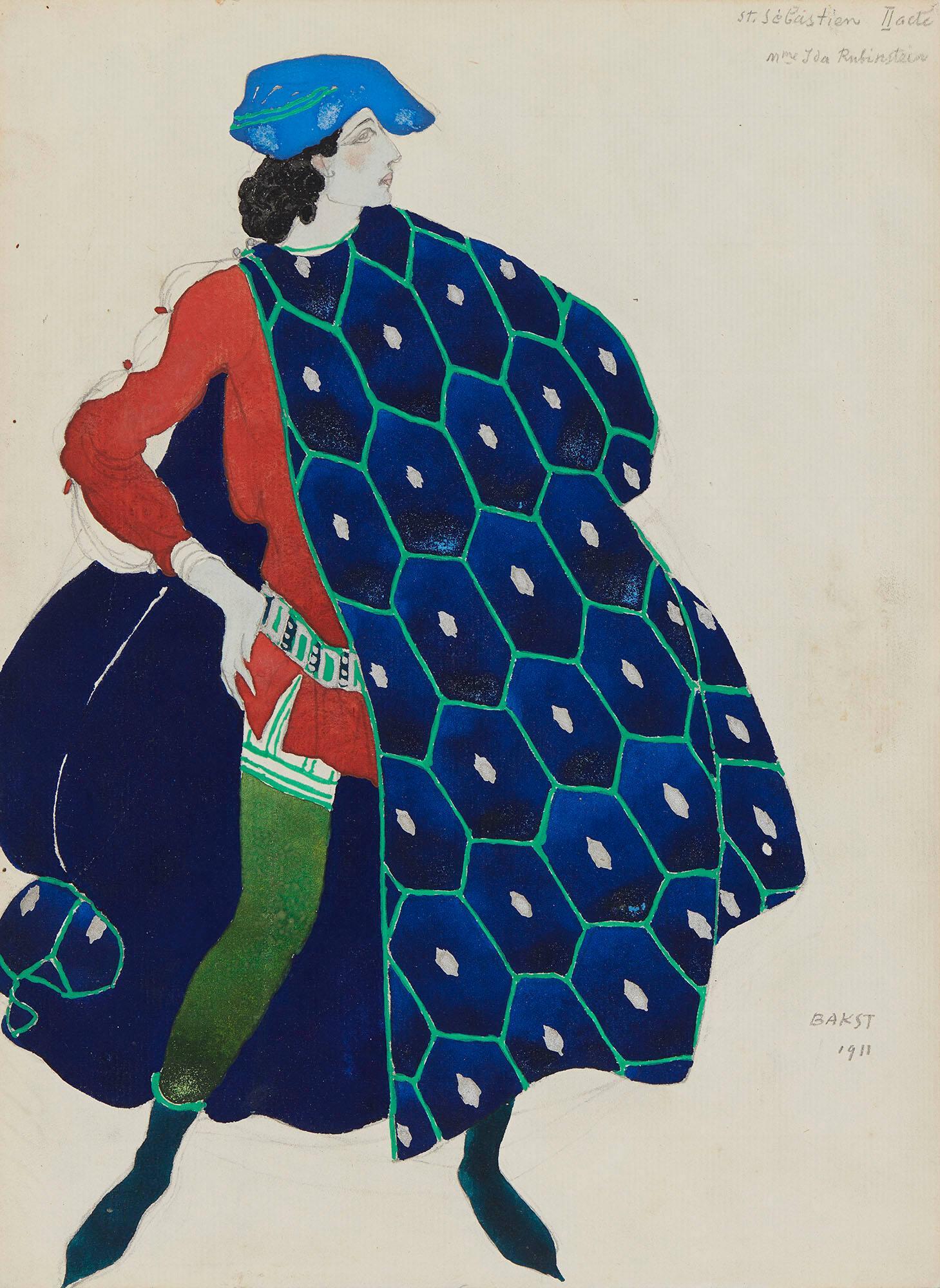

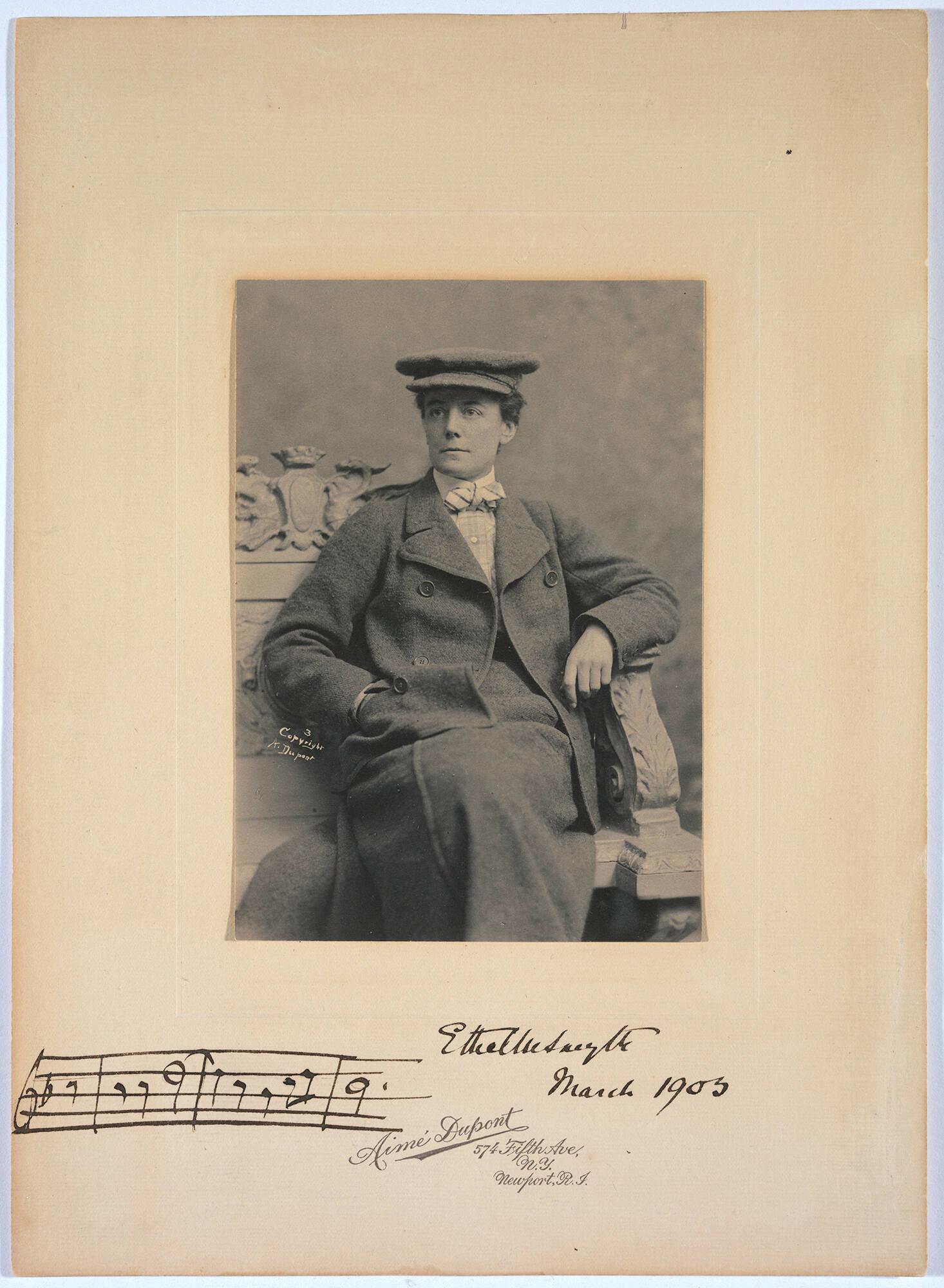

As a musical patron, Isabella Stewart Gardner supported the creation of new operas. She encouraged a collaboration between her two close friends: the composer Charles Martin Loeffler and Japanese scholar and writer Okakura Kukuzo. Kukuzo had written a libretto, and Gardner wanted Loeffler to set it to music—although the project was never completed. On another occasion, she mounted an operatic premiere at her Museum, hosting the first performance of her friend Amherst Webber’s one-act opera Fiorella. Ethel Smyth, the first woman to have her work performed at the Metropolitan Opera in New York in 1903, paid Gardner a visit the same year to seek support in bringing her work to Boston. A signed portrait from their meeting is inscribed with a few handwritten bars from her opera Der Wald.

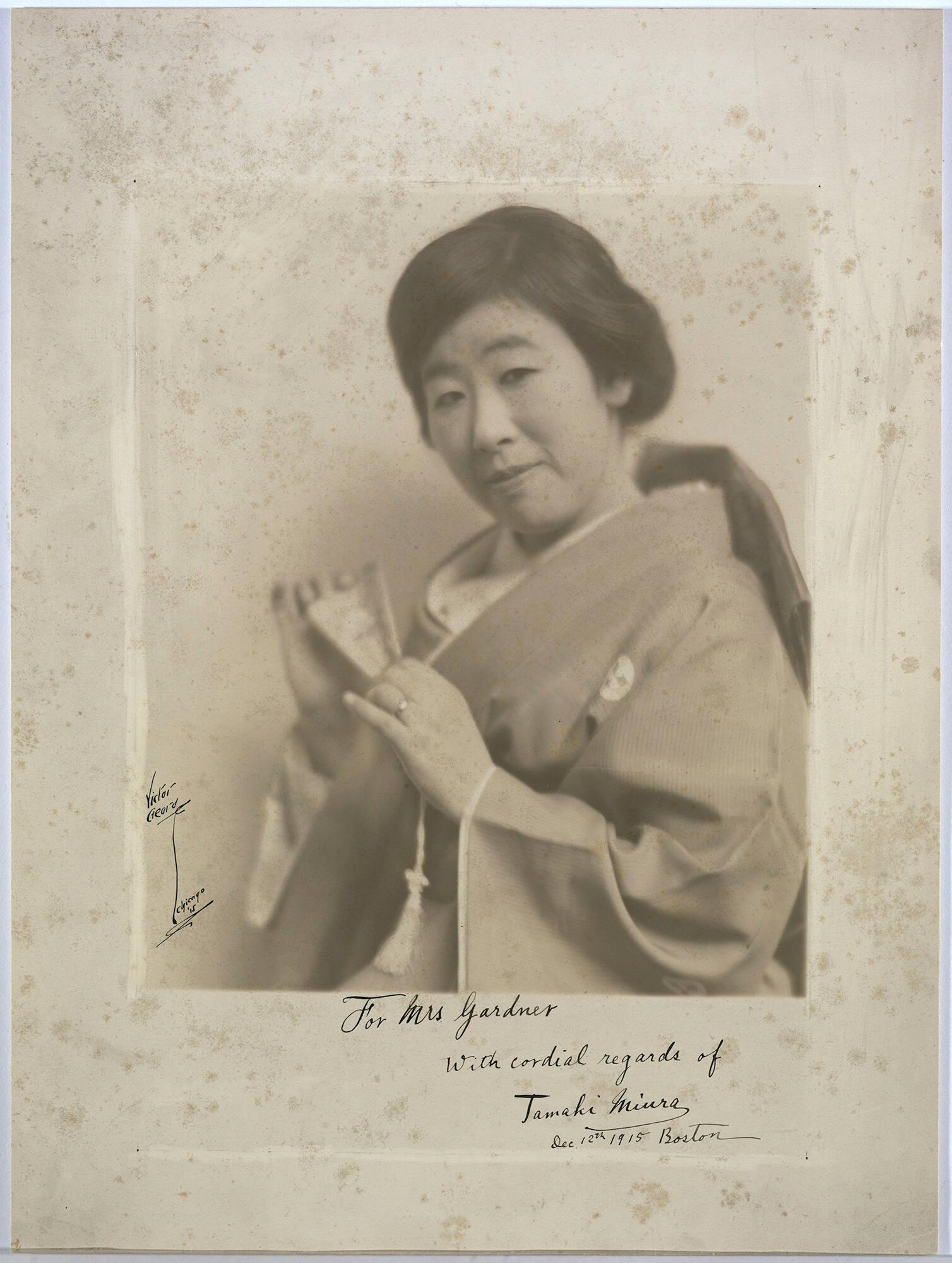

During Isabella Stewart Gardner’s lifetime, opera was one of the few classical music disciplines where women could perform professionally. At the time, orchestra musicians, conductors, instrumental soloists, and most chamber musicians were all men. Gardner both admired and befriended some of the most famous operatic divas–meaning famous star singers– of her time. These friends included Tamaki Miura, one of the first Asian opera singers to establish an international career, and Amalie Materna, a legendary soprano who originated the role of Brünnhilde in Wagner’s famed Ring Cycle. Nellie Melba, a superstar soprano, performed at the Museum and kept up affectionate correspondence with Gardner, calling her “the most wonderful and charming lady in the world.”

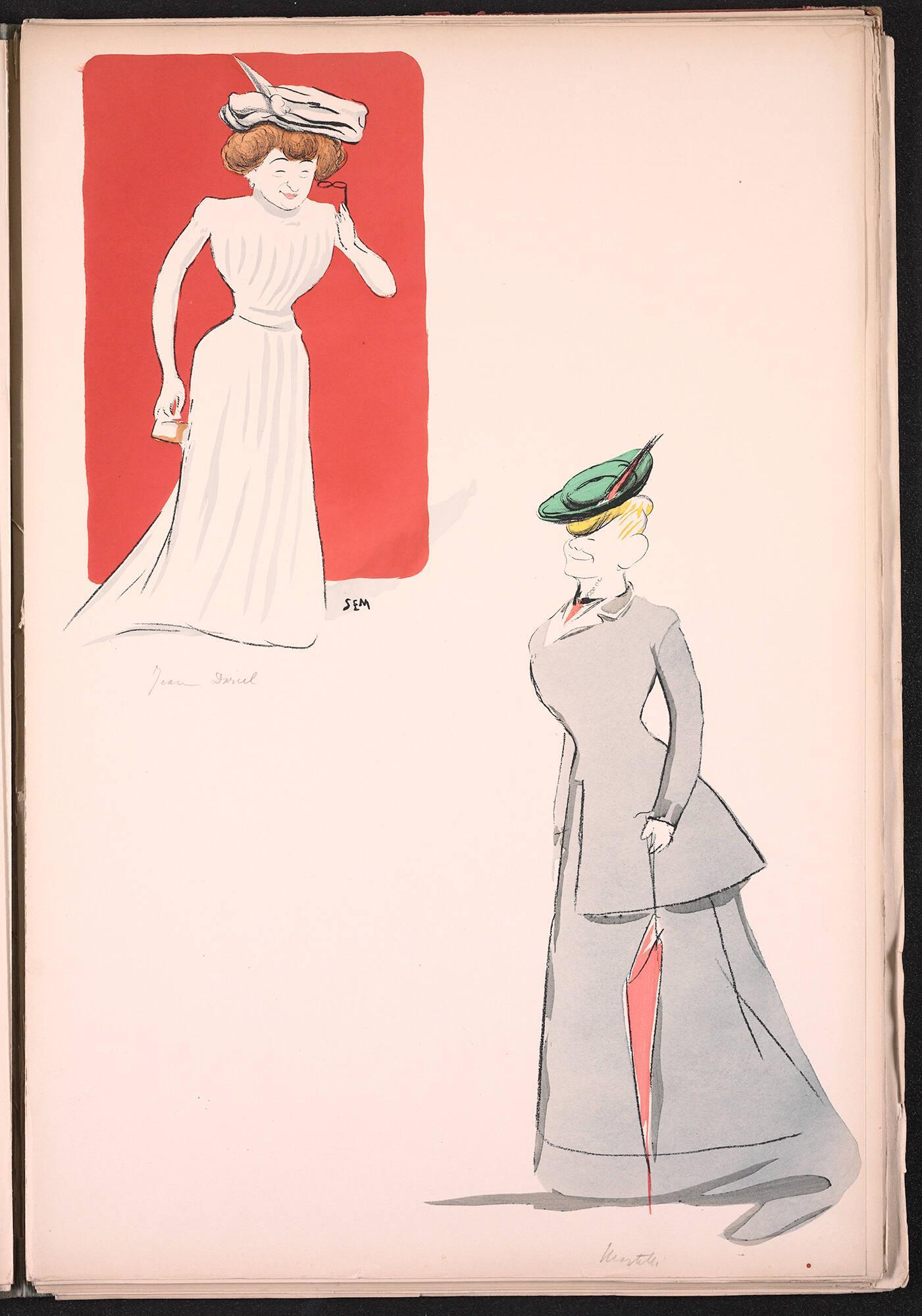

Nineteenth century opera attendees took part in a performance of their own, dressing in elaborate costumes to see and be seen by other patrons. In top hats and tiaras, people like Isabella Stewart Gardner and her husband Jack, participated in this pageantry. The spectacle became so extreme it was the subject of a series of caricatures, like the ones here that Isabella collected.

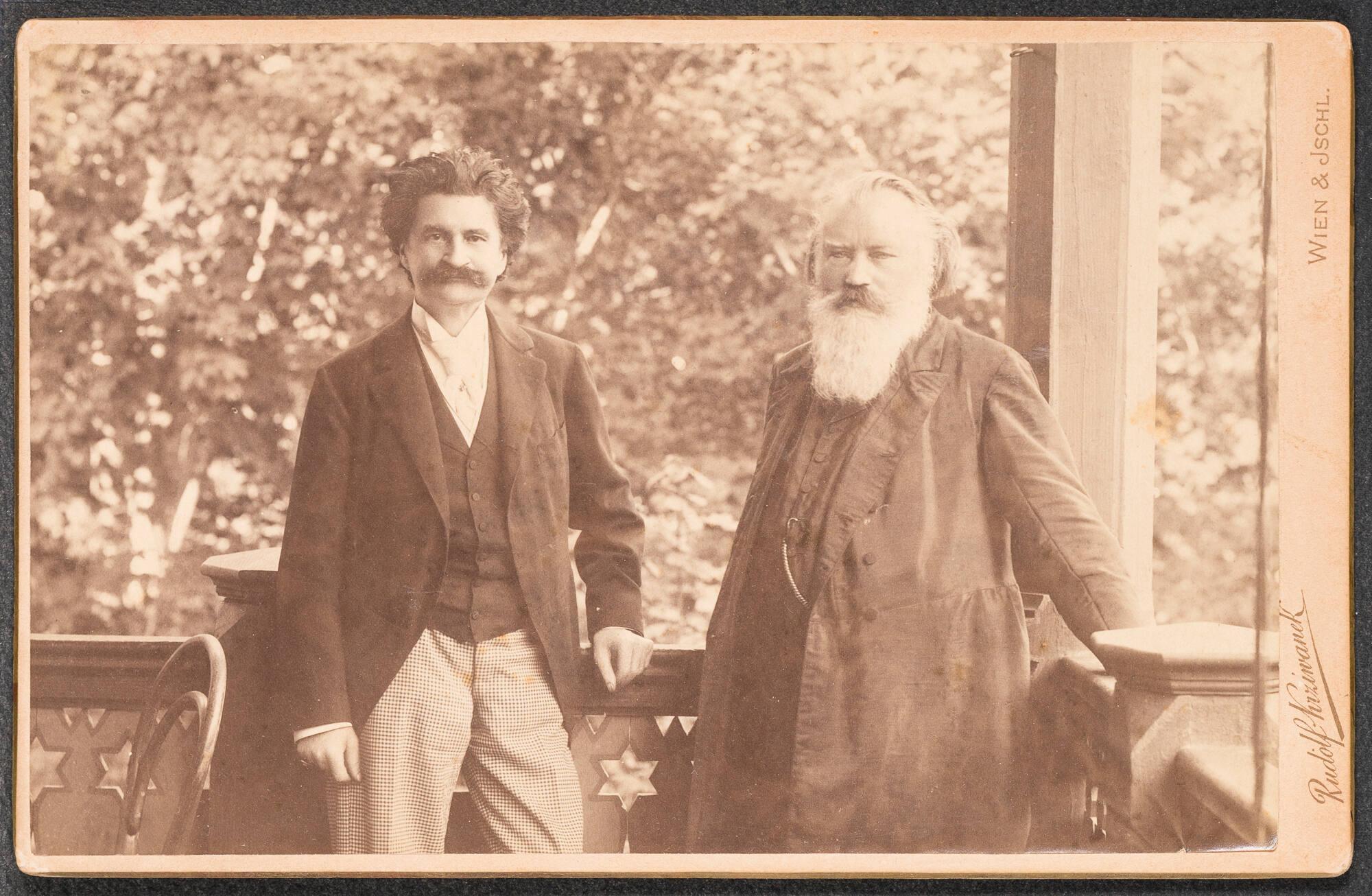

Isabella Stewart Gardner adored music and famous musicians. Gardner traveled to the hometown of the great Johannes Brahms intent on meeting the composer, and she saved a cigarette butt that Brahms had smoked as proof of their encounter. On another occasion, Gardner traveled to Europe in the hopes of meeting renowned composer Franz Liszt, only to find he had died just before her arrival. She saved a lock of his hair, however, and cast the first shovel of earth on his grave.

Isabella Stewart Gardner was a friend and patron to many musicians and composers. Before creating her Museum, she held concerts at her homes in Boston and Brookline. She opened her Museum with a concert and continued to bring some of the world’s best musicians to perform there until her death. She commissioned new music and even bought world-class instruments, like a Stradivarius violin, that she gave to her friends to play. It is no surprise that the Gardner Museum has the oldest Museum-based concert series in the country. The museum originally included a dedicated music room, although she demolished it in 1914 to make way for more gallery spaces–including the Tapestry Room and Spanish Cloister.

Isabella opened her new museum with music–a concert by the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO), conducted by her friend Wilhelm Gericke, featuring the Overture to The Magic Flute. It was second on the program that she planned for the momentous opening night. Gericke’s score for the opera, which is preserved in the archives of the BSO could be the music he used to conduct the musicians playing this piece when the Palace was first unveiled to the public.

In November 1991, Sendak spoke at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum as part of a lecture series called Eye of the Beholder, which brought a range of artists and thinkers to the museum. Although the museum does not have a transcript of Sendak’s lecture, the director’s introduction mentioned his stage designs.

The Magic Flute

Austrian composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) wrote The Magic Flute in 1791 shortly before his death at the age of thirty-five. The opera follows the quest of Prince Tamino and his sidekick Papageno as they seek to rescue Pamina, the beautiful daughter of the Queen of the Night, who has been kidnapped by the mystical high priest Sarastro. With the aid of their magic flute and bells, Tamino and Papageno ultimately save Pamina, and their ordeals lead them to develop a deeper understanding of true love and happiness.

Sendak called Mozart “the artist I most admire in the whole world” and considered The Magic Flute one of the greatest works of art ever made. When opera director Frank Corsaro (1924–2017) invited Sendak to create the stage design for a new Magic Flute production in 1978, he observed that Sendak’s picture books uniquely balanced darkness with levity. This delicate equilibrium translated beautifully to Sendak’s designs for The Magic Flute, an opera that similarly blends drama and humor. Sendak made many preparatory sketches as he worked through the stage and costume designs for the production, which debuted in Houston in 1980.

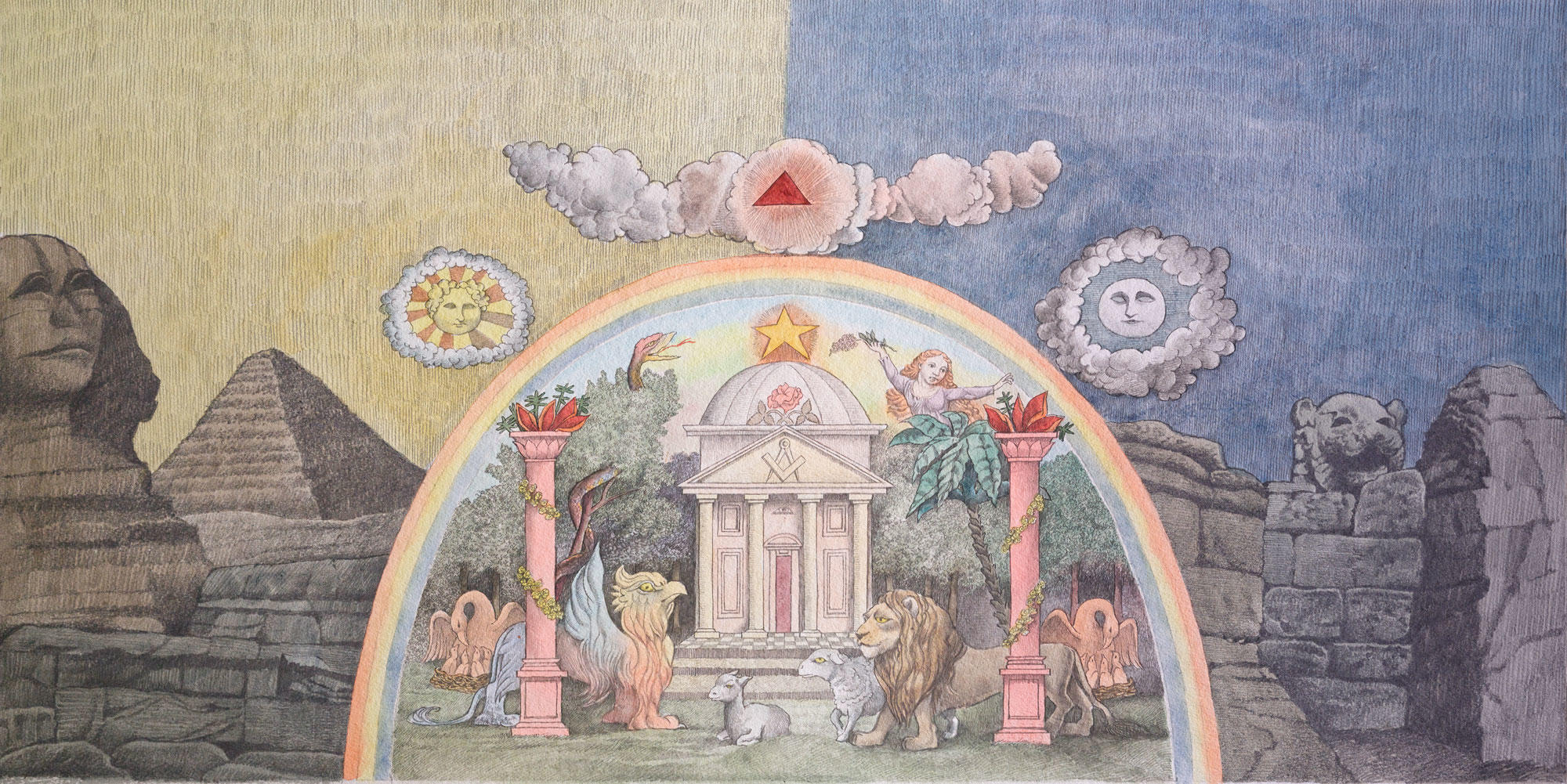

Design for Temple of the Sun backdrop, finale II, 1979–80

Watercolor and graphite pencil on paper on board

TC2022.01.26

Object Description

This pencil drawing and watercolor work on paper is in landscape orientation. It shows a scene of ancient civilizations. Moving from left to right there is a large sphinx, a pyramid, a rock wall topped by a stone female lion head, and an obelisk. The foreground contains a horseshoe shaped rainbow containing a scene of a central domed, white, Greek temple flanked by a pair of pink columns in a tropical garden-like setting. The dome has an orange star with a red halo surrounding it. To the right is a woman with red hair holding a purple flower and to the left is a serpents head. Below there is a palm tree, mythical creatures, and other animals including a griffin, a lion, goats, and two swans surrounded by their cygnets. Above the center of the rainbow there is a line of horizontal clouds with a central pink circle enclosing a red triangle. The background sky is divided in half by color with a yellow section on the left. It contains a circular drawing of a sun with a human face. The right half of the sky is deep blue with a circular drawing of a moon with a human face.

Sendak and the Old Masters

In addition to having a passion for classical music, Sendak loved works of art by the Old Masters—famous European painters working before 1800. He even spoke at the Gardner Museum in 1991 about his appreciation for the Italian Renaissance artist Andrea Mantegna (1431–1506), whose rock formations inspired Sendak’s designs for the Magic Flute.

Setting the (Miniature) Stage

New to stage design, Sendak took an extra step to translate his designs for The Magic Flute from two-dimensional drawings to three-dimensional installations. These hand-rendered dioramas allowed him to create miniature models of how the sets would appear on stage. In this form, he synthesized ideas from his earlier sketches and fully integrated many art historical references into the final stage designs.

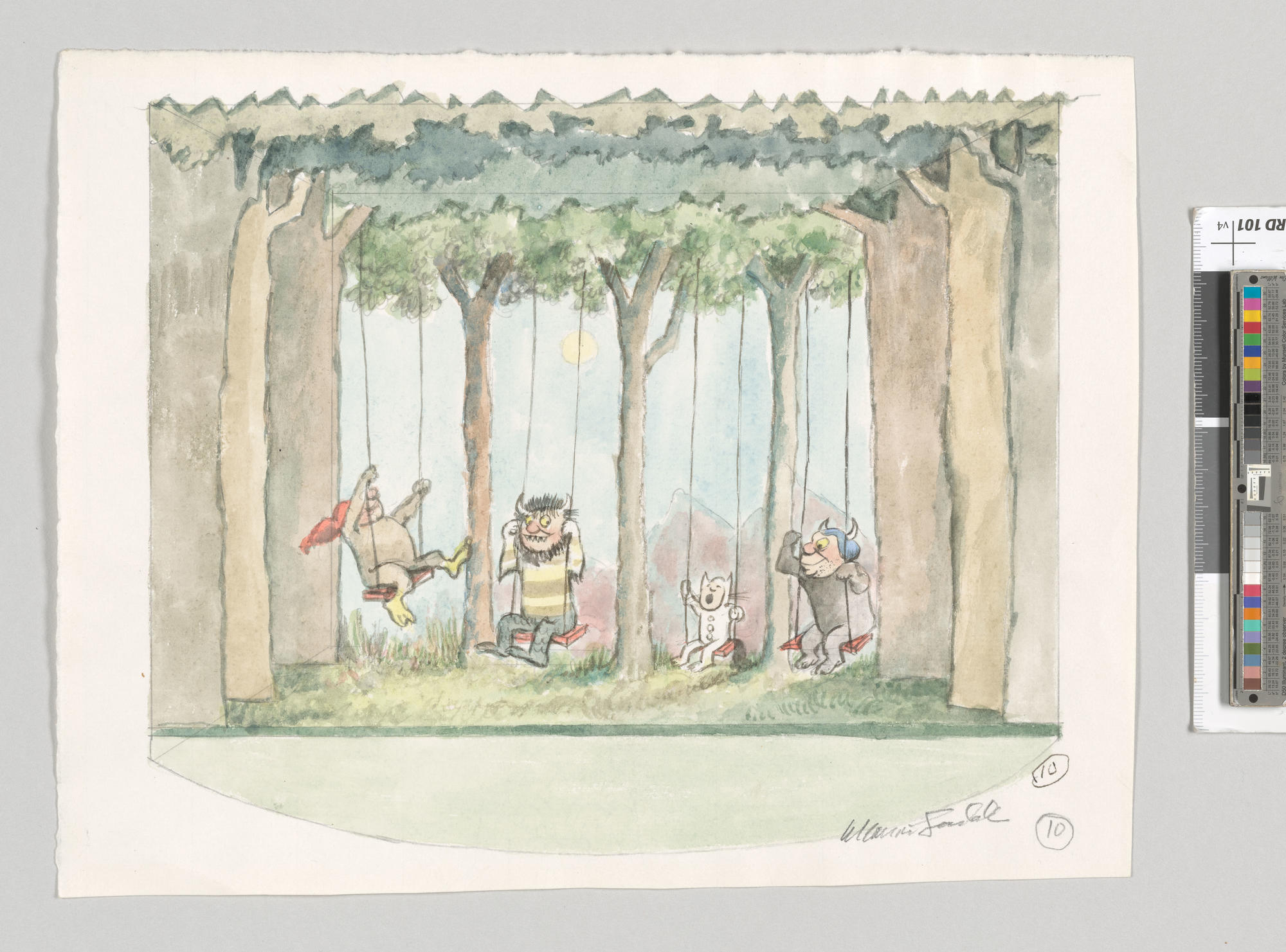

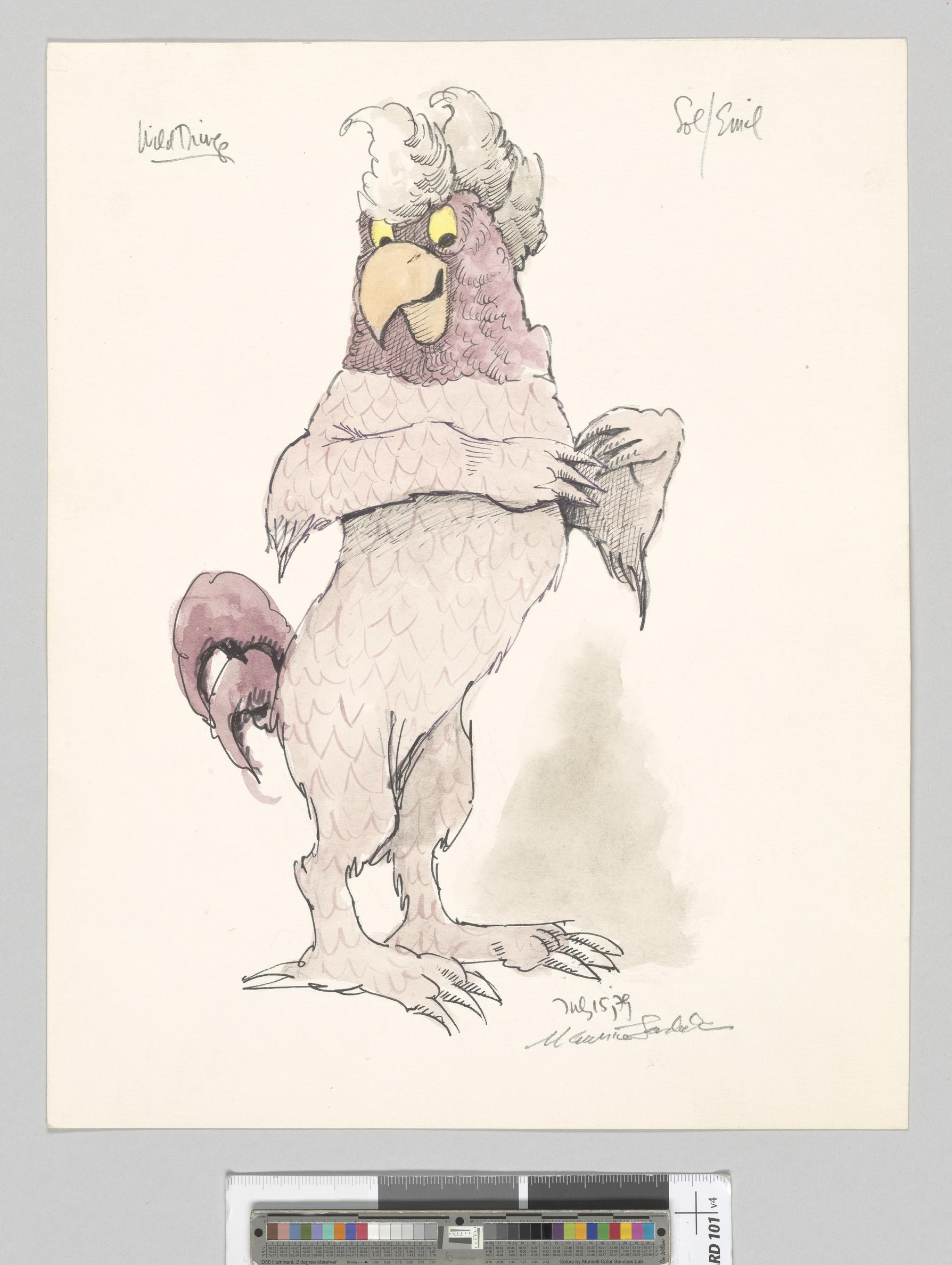

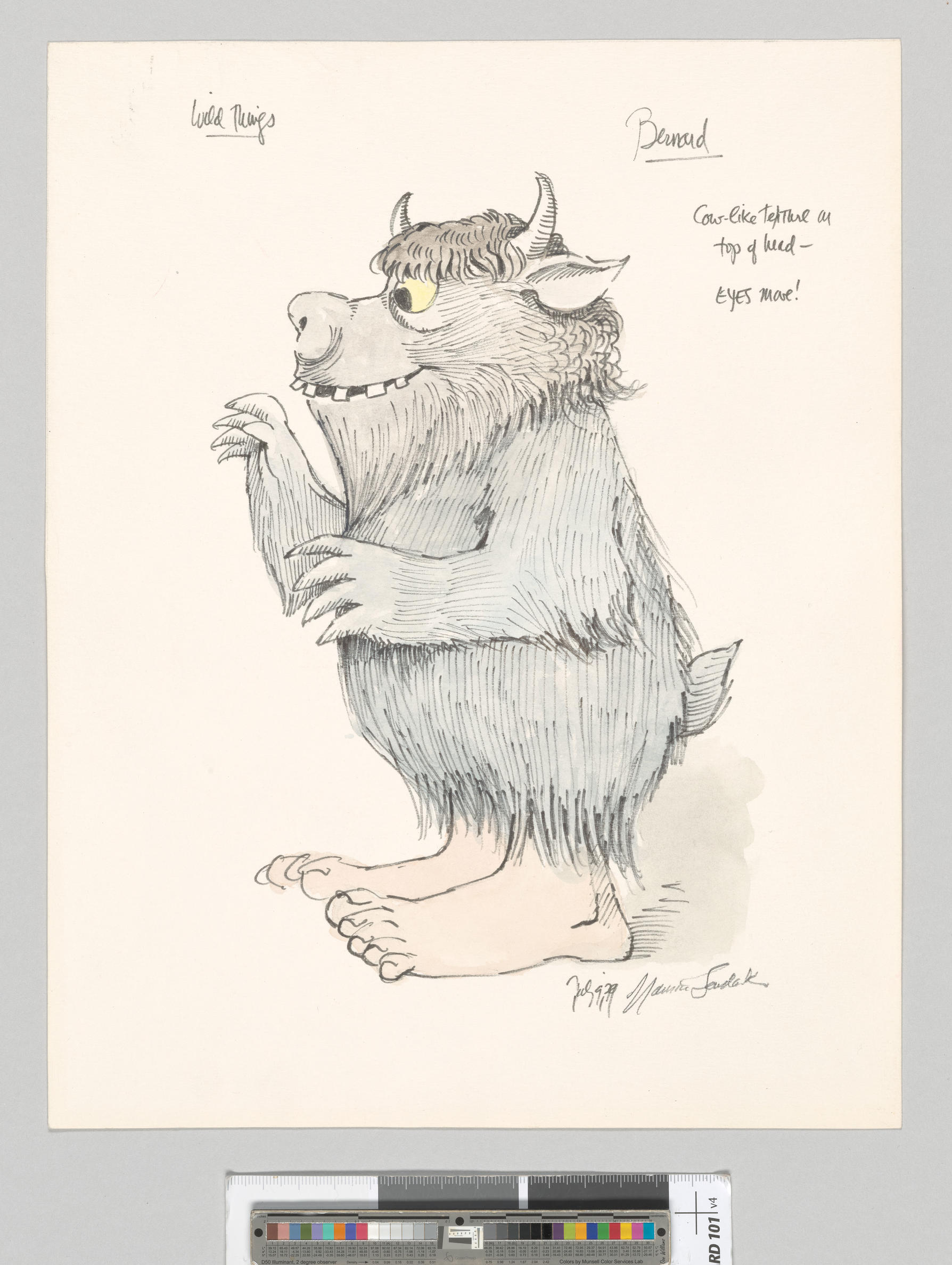

Where the Wild Things Are

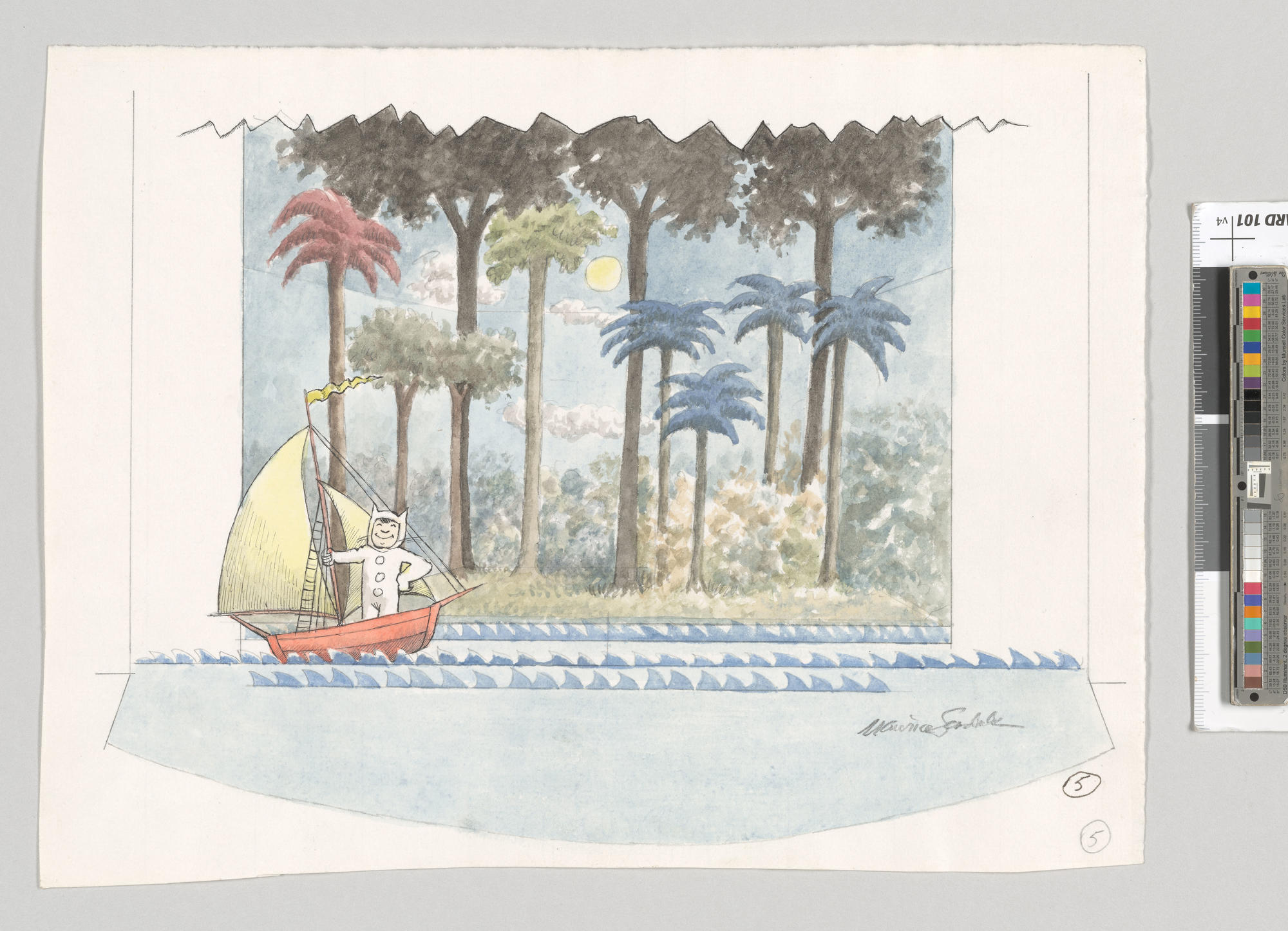

The opera Where the Wild Things Are is based on Sendak’s acclaimed 1963 picture book of the same name. With music by British composer Oliver Knussen (1952–2018), it premiered in an incomplete form in 1980; the finished version was performed in London in 1984.

Like the book, the one-act opera follows Max, a young boy who dresses in a wolf costume and wreaks havoc throughout his house. As a punishment, his mother sends him to bed without dinner. Once in his bedroom, Max’s surroundings transform. He sails to an island inhabited by the frightening Wild Things. The young boy ultimately becomes their king but grows lonely and—to the Wild Things’ disappointment—sails home to find a hot supper waiting for him.

In the more than fifty years since they were created, Max and the Wild Things have enchanted audiences–first on the page, and then on the operatic stage. By emphasizing the volatility of its young hero, his conflict with his mother, and the potential danger posed by the Wild Things, Sendak’s story does not shy away from themes of struggle. In doing so, it has become a touchstone for generations of children navigating the complex and sometimes scary real world.

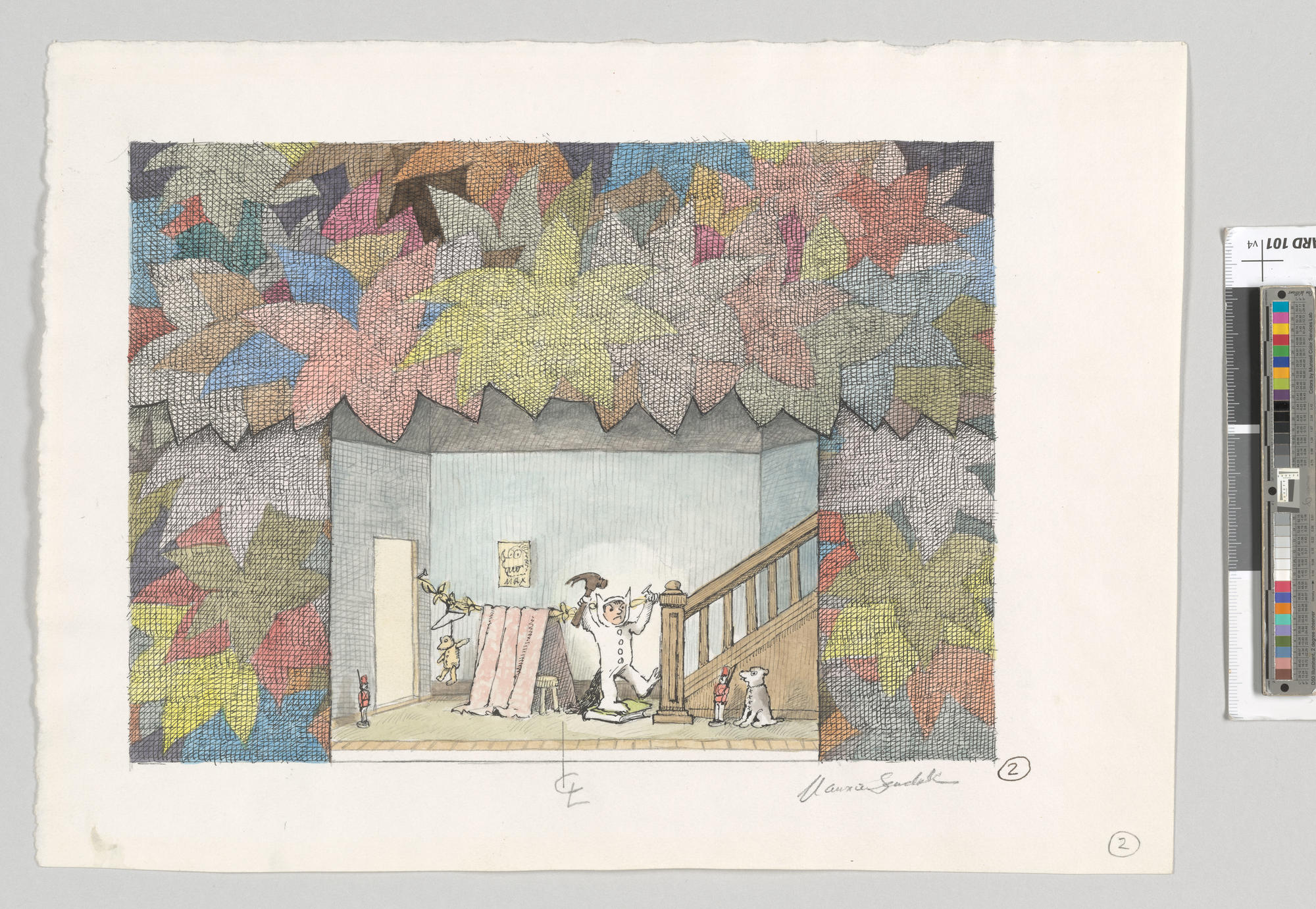

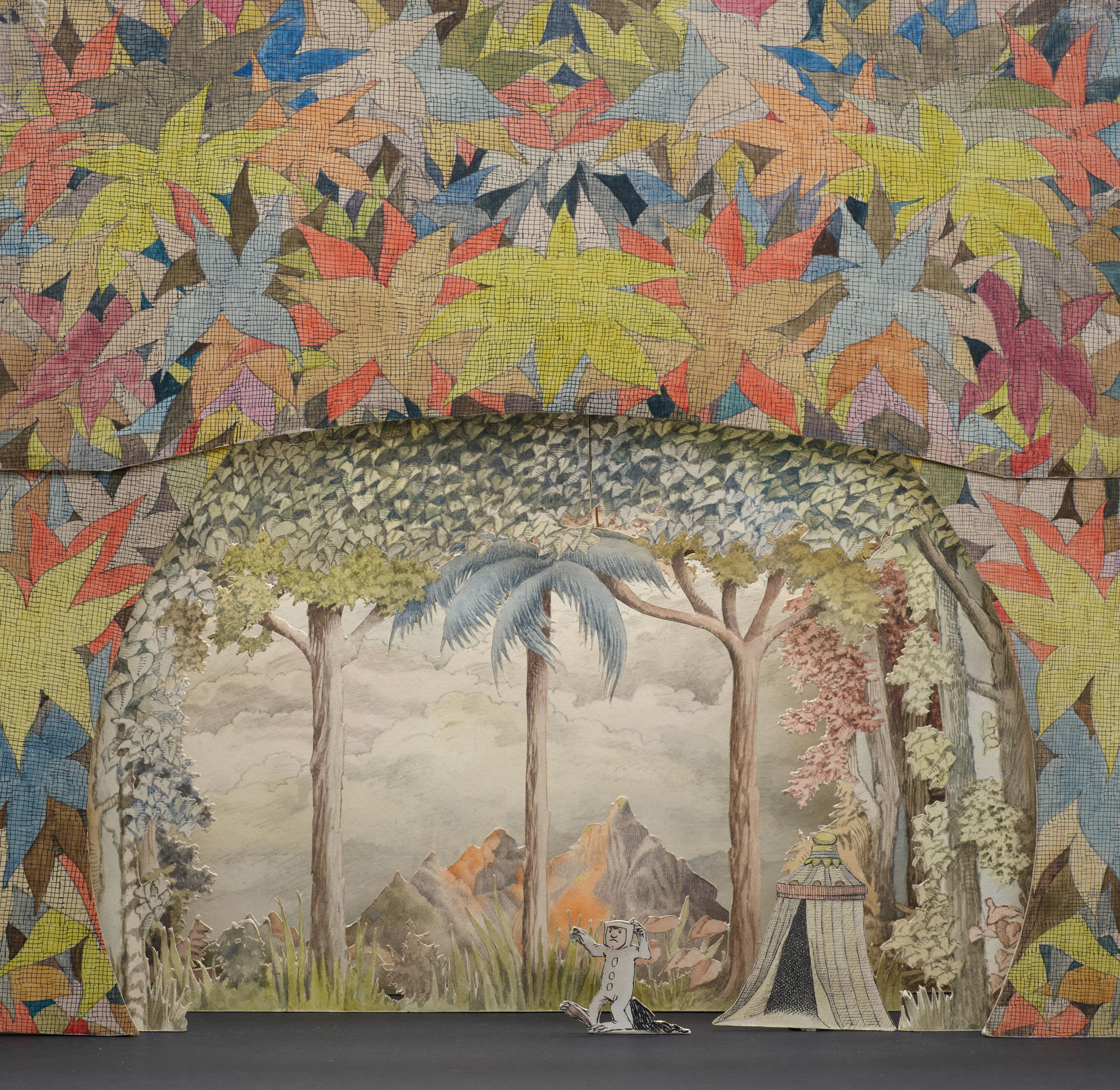

Diorama of Max in the forest, 1979–83

Watercolor, pen and ink, and graphite pencil on laminated paperboard

TC2022.01.116-120, 110b

Object Description

This diorama, or three-dimensional model, is executed in watercolor, pen and ink, and graphite pencil on laminated paperboard. The focus is a child, Max, who is seen on the center right side of the stage dressed in his white wolf costume with protruding ears from the hood, buttons up the front, large front and rear paws, and a long, dark, furry tail. He is depicted striding toward our left with his arms raised. He has a menacing look on his face. A white fabric tent with a cupola-like top is seen behind him to our right. The sides of the tent are gracefully draped to form an opening to the dark interior of the tent. Behind Max along the back edge of the stage are three widely spaced tall trees growing in a grassy landscape; two are topped with green foliage and the one in the center has light blue palm tree like leaves. Further in the distance are several tan mountain peaks, two of which have orange sides on their left. The sky is gray and has many white clouds throughout. There are large, tall trees bordering each side of the stage with pale pink, blue, and white flowers and foliage. This foliage, seen as small white, blue and gray leaves, extends above the acting area of the stage to form a short canopy. The proscenium arch is beautifully decorated with saturated pastel colored, large leaf-like shapes that have a light gray cross hatched pattern throughout.

Storyboards are more commonly associated with film or television than with books or theater design, but Sendak often used them to map out his books and theatrical productions. They were an essential part of his process to bring Where the Wild Things Are to the stage. “I have found that telling a story by means of related, sequential pictures allows me to ‘compose’ with assurance and freedom,” he said. His storyboards range from a series of quick pencil drawings to colorful, charming watercolors.

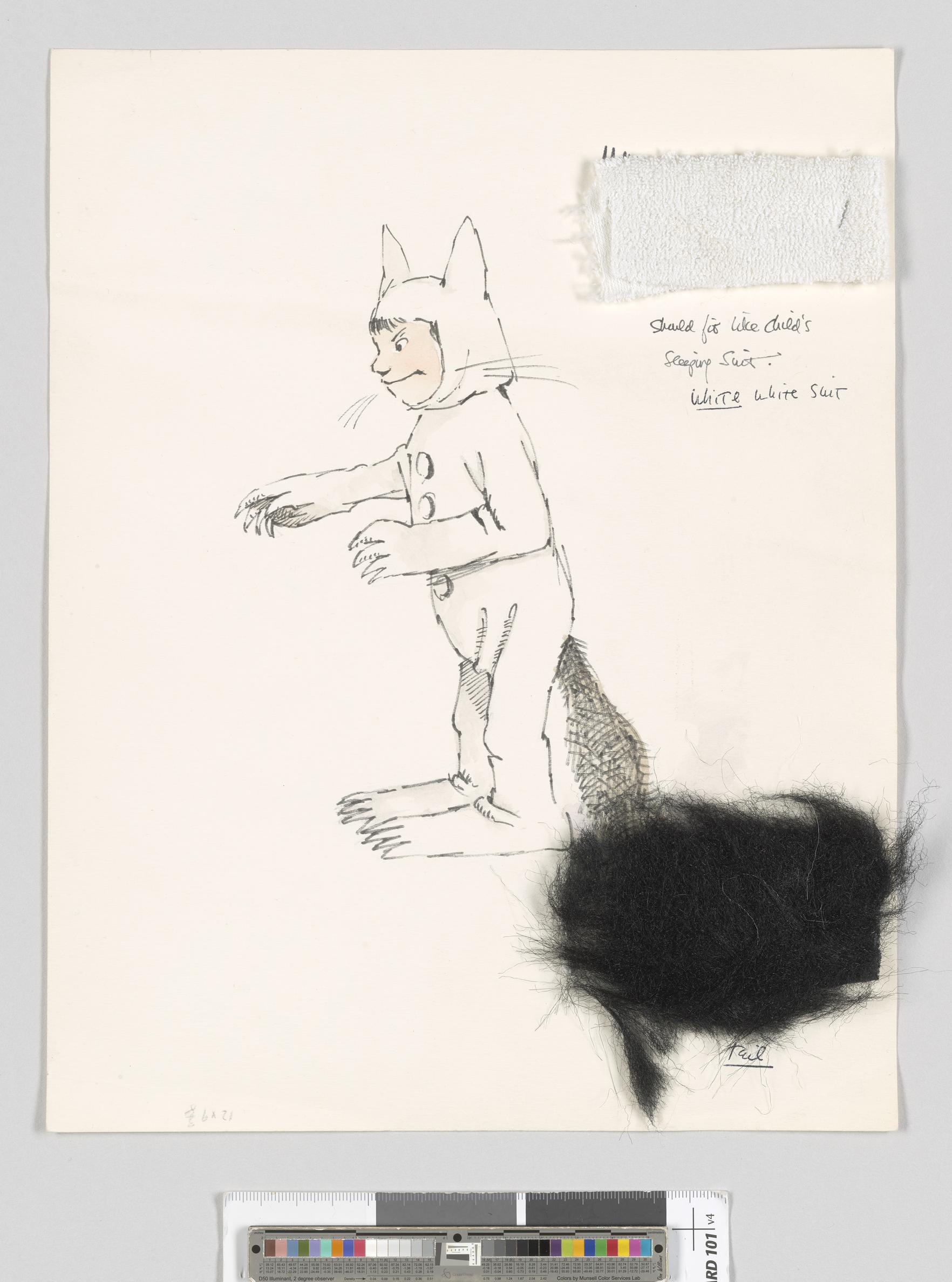

These drawings show notes and concepts for the costumes for Where the Wild Things Are. In the opera’s completed 1984 version, each Wild Thing weighed up to one hundred fifty pounds and was operated by three people: an offstage singer who performed the voice; a puppeteer who inhabited the suit and controlled the arms, legs, and head; and an offstage remote-control operator who made the eyes move.

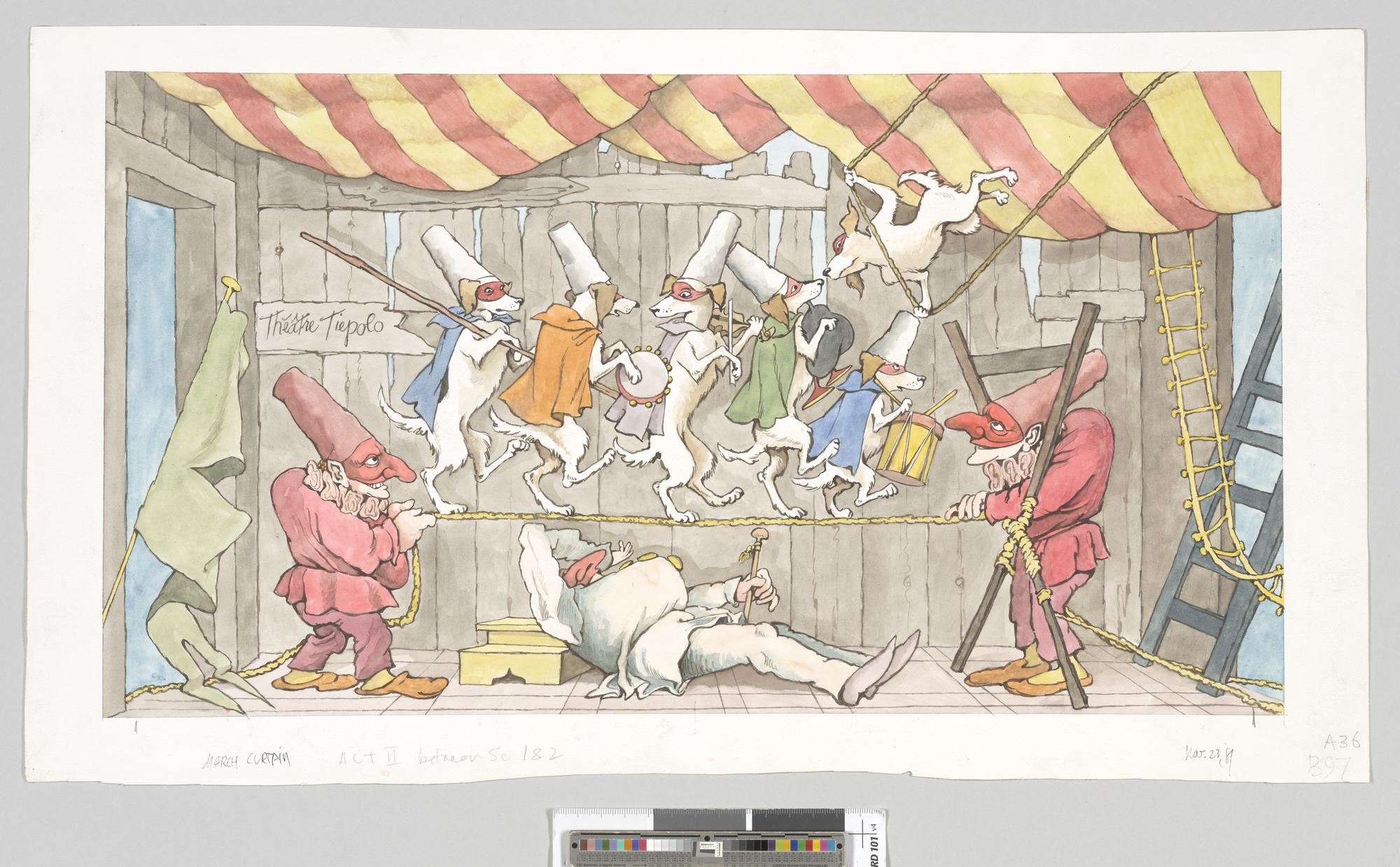

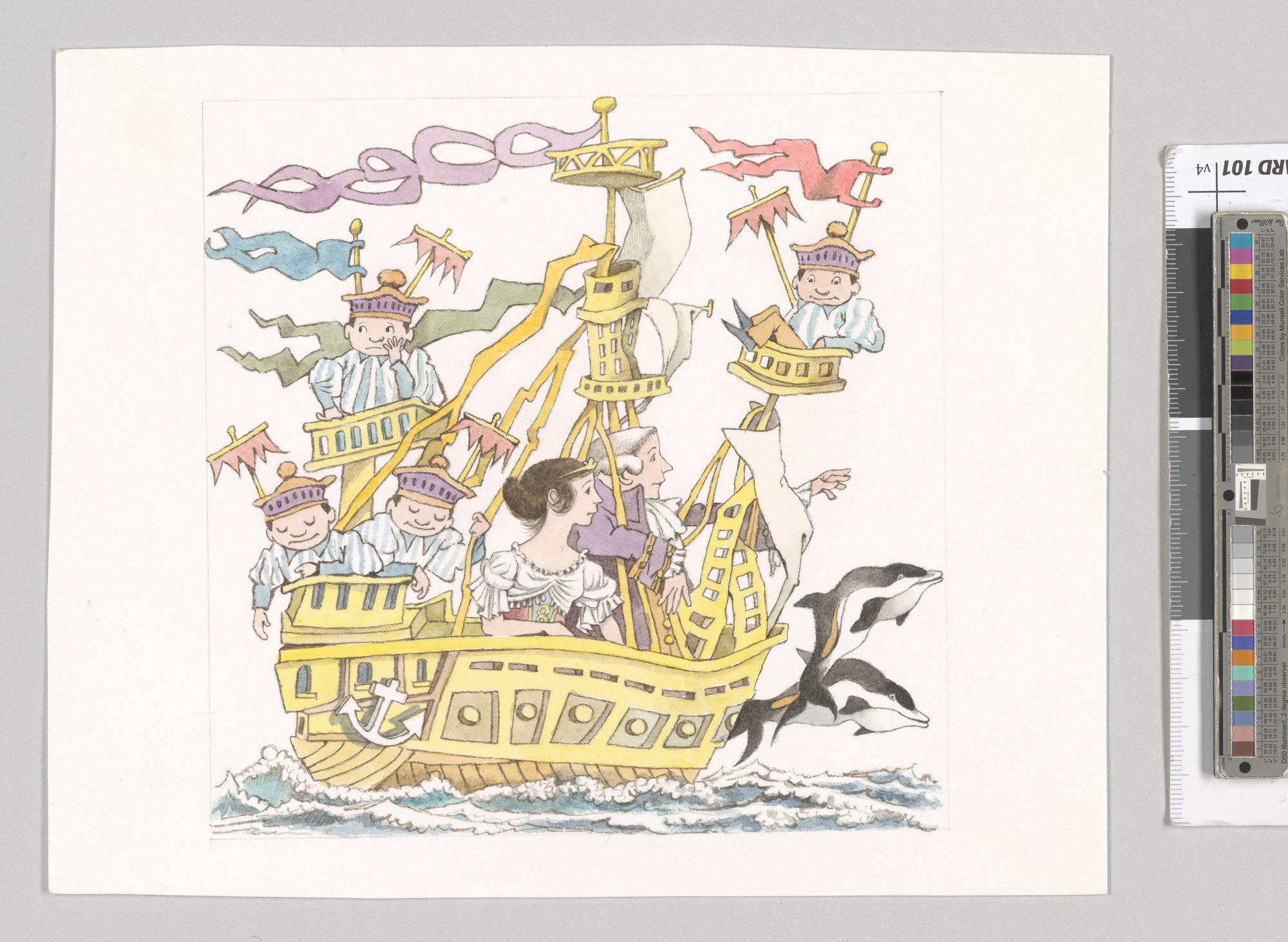

The Love for Three Oranges

The Love for Three Oranges is a satirical opera written by Russian composer Sergei Prokofiev (1891–1953) and first performed in 1921. Based on an eighteenth-century Italian play, it retells a fairy tale of a cursed young prince who cannot laugh—even at funny performances and parties. To break the curse, he has to track down three oranges, each of which contains a princess.

Following Prokofiev’s choice to adapt an Italian play in the Renaissance tradition of the commedia dell’arte (comedic theater productions featuring masked characters), Sendak found inspiration in drawings by the Venetian artist Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo (1727–1804). In Sendak’s version of the opera, conceived alongside director Frank Corsaro, the French Revolution is the backdrop to the play within a play: an Italian theater troupe performs the opera in a French seaport town. The opera debuted at the Glyndebourne Festival Opera in Sussex, England, in 1982.

Sendak’s colorful, playful drawings for the costumes and sets for The Love for Three Oranges became the templates for the completed set pieces and costumes used when the opera was performed, bringing the worlds Sendak created on paper to life for audiences. The artist delighted in seeing his work move from two-dimensional images to three-dimensional objects that not only moved but were animated by performers and music.

Sendak often sought inspiration for his stage design from art historical sources. This is particularly clear in his designs for The Love for Three Oranges, which bear a striking resemblance to the quirky and playful drawings by eighteenth-century Italian artist Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo. Sendak paid homage to the artist by naming the troupe that performs The Love for Three Oranges within the opera “Théâtre Tiepolo.”

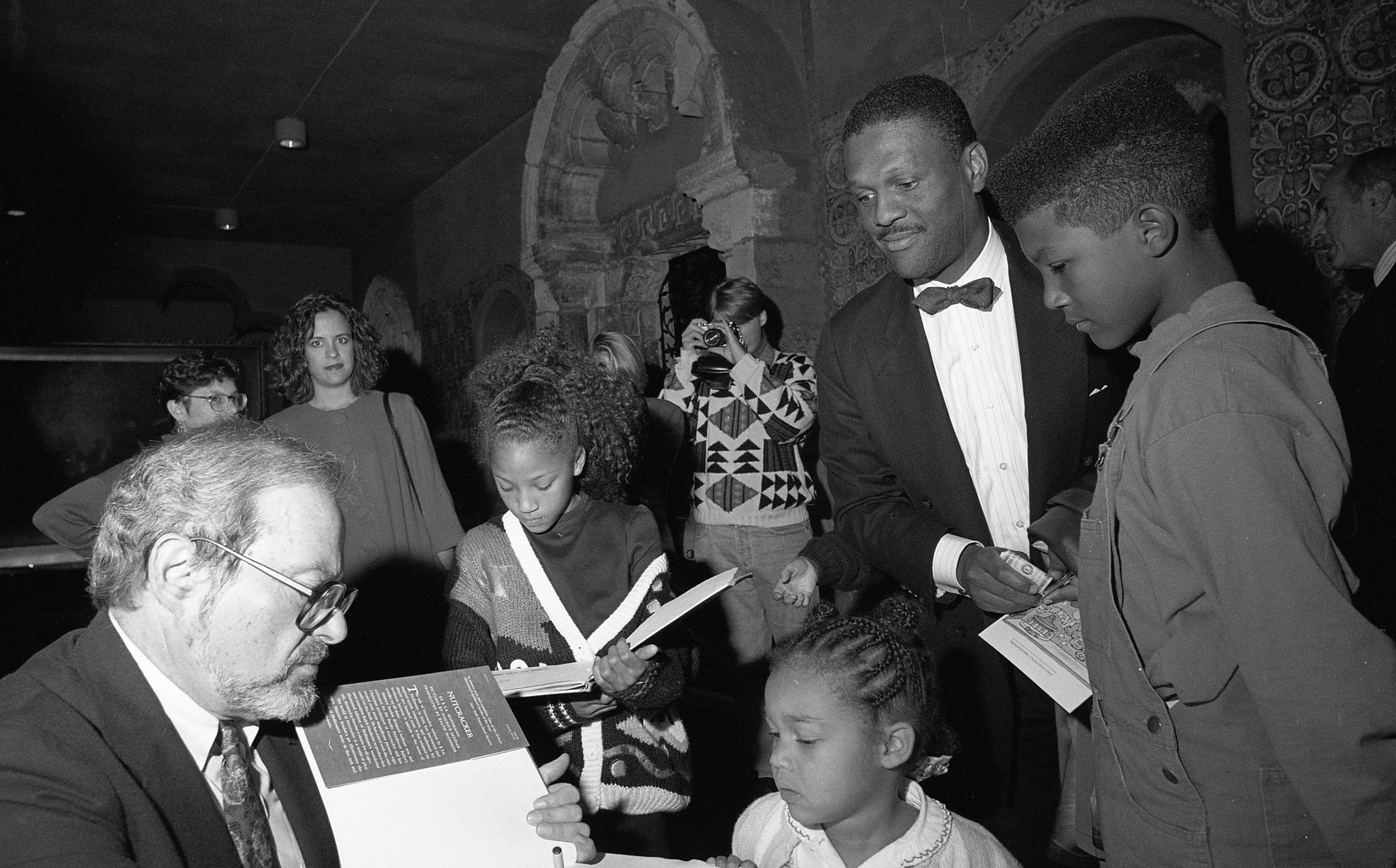

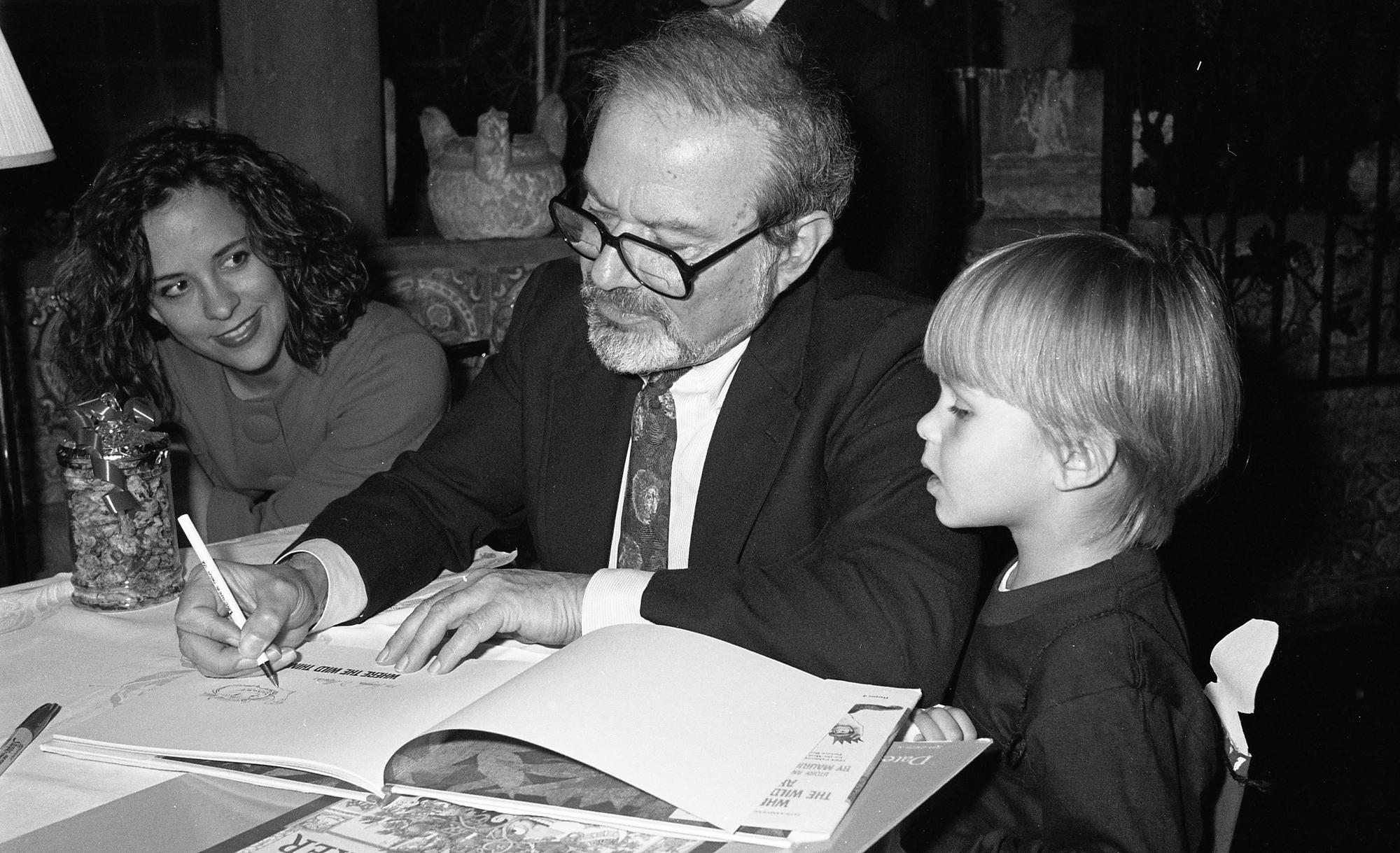

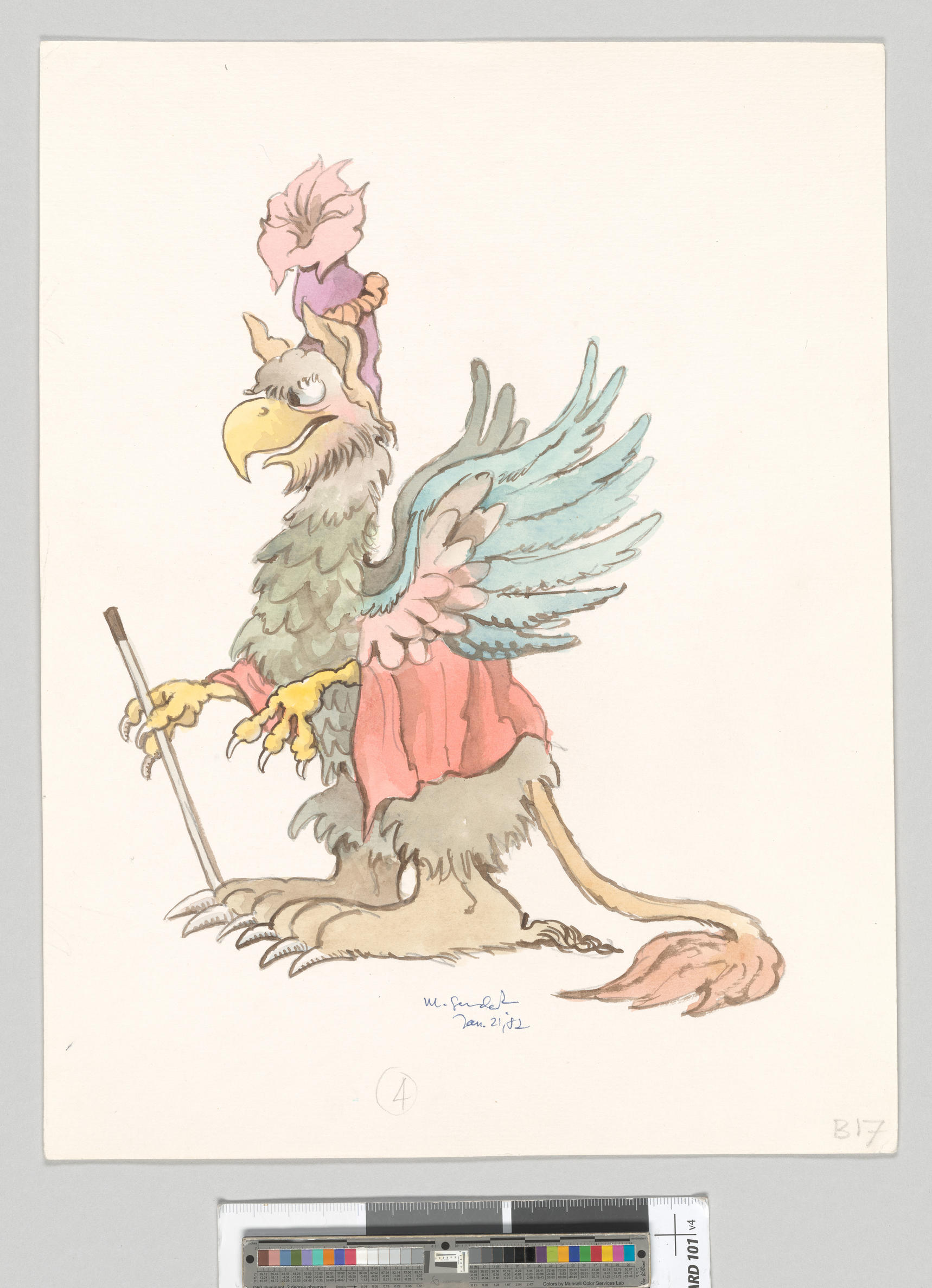

The Nutcracker

When Seattle's Pacific Northwest Ballet invited Sendak to design a new Nutcracker, he wanted to decline. "Who in the world needed another Nutcracker?" he reflected later. As Sendak saw it, in the traditional ballet a little girl dreams, has adventures, and then "a whole bunch of grown-ups dance at her party. No kid would want that."

He accepted the job when it was clear he could bring something new to the Christmas mainstay, which he learned diverged radically from the short story that inspired it. He presented Clara, the protagonist, as a prepubescent girl of twelve rather than a young child. After rescuing the Nutcracker, she transforms into a grown woman. This telling hews more closely to E. T. A. Hoffmann’s (1776–1822) original 1816 tale, which is darker than the ballet—and once again shows Sendak’s willingness to make work for children that did not overly simplify or sugarcoat stories. He wrote that existing versions were “smoothed out, bland, and utterly devoid not only of difficulties but of the weird, dark qualities that make it something of a masterpiece.” The production premiered in Seattle in 1983 and was performed annually for more than thirty years in addition to being made into a film.

In his production, Sendak centered the character of Drosselmeier, the eccentric clockmaker who gives Clara the Nutcracker and launches the story’s action. Sendak’s many drawings of Drosselmeier suggest he identified with the character. He depicts the clockmaker in various guises—including in drag as Mother Ginger, who ultimately appeared in the film but not in the stage version of the ballet. This avatar’s traversing of gender lines and identities was perhaps a reference to Sendak’s navigation of his own identity and sexuality. Sendak was gay and privately out, navigating a homophobic social climate for much of his life. Once societal views had shifted, he came out publicly in 2008 at the age of eighty.

Design for act curtain, Drosselmeier’s studio, 1983

Gouache and graphite pencil on paper

TC2022.01.68

Object Description

This horizontal pencil on paper drawing with softly colored gouache is labeled at the bottom in capital letters, ACT CURTAIN FOR TOY THEATRE, and is signed M. Sendak—Feb 15-22nd, ’83. The design shows the figure of Drosselmeier from the Nutcracker in his toy studio. Drosselmeier is drawn as a tall, skinny figure stooping under the ceiling of the room, leaning forward out of a green and gold frame, with his arms and legs bent akimbo outward and his face turned downward and slightly to our left. He has light skin, pale and thick straight hair sprouting upward and outward, a black eye patch, a long nose and chin, and a slight smile. He is wearing a white shirt with a ruffle at the neck, a tan vest, green pants that end at the knee, and a pink coat open at the front. His tall socks have blue and white vertical stripes, and his clownishly long brown shoes have square gold buckles. Drosselmeier is surrounded by three toy statues bearing the names of figures from the Nutcracker on their circular bases. To our right are the Mouse King, wearing a layered, multi-colored costume with a hooded robe and gold crown and carrying a downward-facing sword, and the Nutcracker, wearing his red and gold uniform with a red crown and carrying an upward-facing sword. To our left is Pirlipata, a chubby figure with light-colored skin, bulging eyes, wide cheeks and chin, and a long horizontal slash of a mouth. Pirlipata is wearing a white dress with a pink ruffle at the bottom and a gold sash tied at the waist, along with a white bonnet with dark green bows. At the right and left sides of the drawing there are shelves filled with toys, including soldiers in blue uniforms, figures in green and pink dresses and hats, and objects such as a drum. In back of Drosselmeier is a window with many small, square frames, through which a nighttime view of a city is lit by the moon.