In the Long Gallery of the museum are two diminutive 19th-century Italian stools, or sgabelli, tucked under display cases. It’s possible that Isabella placed these stools there because the silvery, shiny upholstery complemented and reflected the vibrant Bardini Blue-painted walls. From 2016-2018, conservation technicians worked hard to conserve and analyze these stools to learn more about their composition and origin. Here’s what they learned.

The Long Gallery, showing the stools along the west wall

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

The History of the Stools

While these stools are 19th-century objects, the sgabello form originated in Renaissance Italy. Small and easily transportable, their size and convenience became a popular form and spread to other European countries. There are examples of sgabelli in period paintings, which show how the stools functioned in Renaissance European interiors.

The Gardner stools have boldly-carved hairy animal paw feet and lyre-shaped legs with scrolling floral carving. The seat upholstery is imitation gilt leather, with geometric stamped patterns and incised fleurs-de-lis.

Gilt leather is a centuries-old craft of applying silver leaf to leather, using a mordant size or glue. The silver usually has decorations of punchwork and varnishes with colored glazes. Yellow glazes are the most common because the resulting metal surface will look like gold, or the silver may be painted for a polychrome effect. There are other beautiful examples in the Veronese Room, where gilt leather panels adorn the walls and upholster the armchairs flanking the fireplace.

Veronese Room, showing leather wall panels and the leather covered armchairs flanking the fireplace

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Sean Dungan

The Stools’ Secrets Revealed

After analysis, the stools revealed that they were not made of 17th-century gilt leather, as previously thought. In fact, they were not made with any of the traditional methods and materials, but something entirely different. These stools are not gilt with silver leaf but with tin leaf, and the inset side panels aren’t leather at all, but gilded paper boards! The Long Gallery stools are ‘imitation’ or ‘faux’ gilt leather.

Analysis began with portable x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (pXRF). It’s a non-destructive elemental analysis that excites electrons on a surface using x-rays, allowing conservators to understand the elemental make-up of materials. In this case, pXRF gave a startling result. Instead of silver, the analysis found tin and zinc. This showed that the metal leaf was tin leaf, and not silver. The zinc remained a mystery until microscopy.

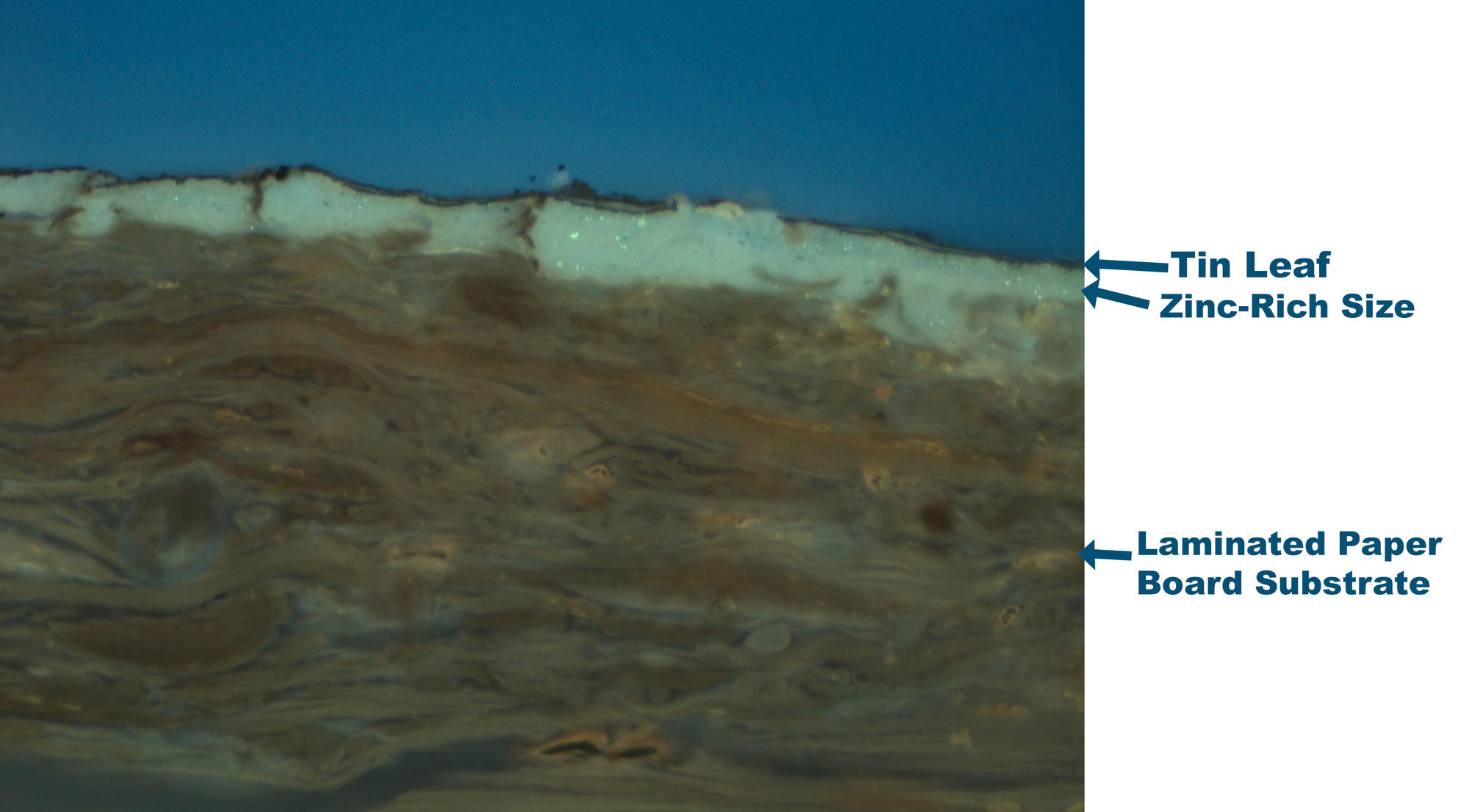

In cross sectional microscopy, conservators take small samples and embed them in a hard resin. They polish them down to reveal a cross-section which they can view under a microscope. First, they found that the side panels were laminated paperboard, and not leather as previously thought.

Microscopy allowed conservators to see the layers of surface decoration, from the thin metal leaf down to the substrate, and the mordant size used to adhere the metal leaf. In ultraviolet (UV) light, the mordant appeared to glitter, which zinc does in UV light. This indicated that zinc was a drier in the gilding process. It was a common additive starting in the 19th century to speed up the cure time of slow-drying oils.

The cross-section from the paper board panel, at 200x magnification viewed with a UV-fluorescent light source. Here you can see the sparkle of the zinc drier in the size layer, and the layered structure of the paper board. Metals do not fluoresce, which is why the tin leaf here looks black.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

The last task was to identify the leather itself. This could help conservators understand the provenance of the stools: Italian gilt leather generally came from goat or sheepskin, whereas calfskin was more common in Northern Europe 1. Conservation scientists used a mass spectrometer to perform protein analysis. This process can identify species- or genus-specific characteristics of collagen-based animal products, such as leather. After a multi-day process, results came back as sheepskin! This helped support the theory that these were indeed Italian-made stools.

Understanding the Process

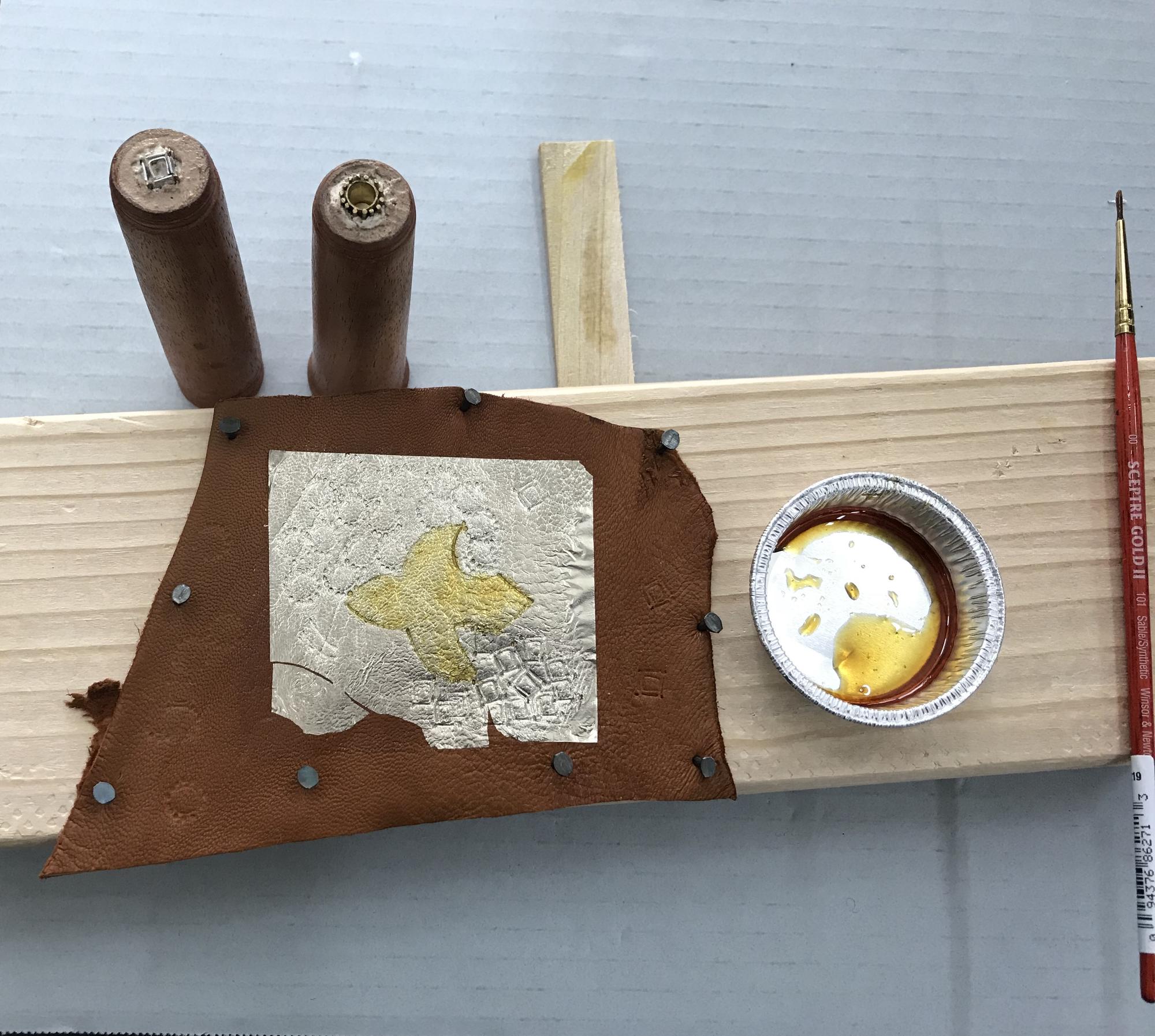

With all the puzzle pieces in place, conservators made a mock-up of the upholstery. They started with sheepskin, tin leaf, and stamp punches using small pieces of metal embedded in epoxy. They concocted a varnish of amber and copal resins, boiled with linseed oil for hours to achieve a golden color, following the traditional process. Imagine how visually striking these stools would have once been, dotted with an elaborate pattern of golden shapes dancing across silver-like metal.

Treating the Stools

The stools were in fairly good condition, on the whole, but the leather was embrittled, powdery to the touch. They had many tears, small losses, and were flaking. The leather tops had brown net covers, similar to hair nets. The caps had successfully protected the leather from further damage but were obscuring the decoration and trapping dirt and dust. Conservators needed to find another solution.

The first step was consolidation. Conservators added a cellulose-based material to the leather where it was powdery to give it strength and hopefully prevent further loss. Next, they bridged tears using splints made of goldbeater’s skin. This material is chemically similar to leather, and had the strength and flexibility needed to work the tiny splints underneath the tears.

During-treatment and after-treatment showing the bridging of a tear with goldbeater’s skin.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

For small losses in the leather, conservators bridged the loss with fine Japanese kozo tissues, then painted them with mica powder-infused acrylic paints. This gave them just a hint of the shimmery tin reflectance.

During-treatment and after-treatment showing the filling a loss with tissue, toned with paints.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Larger losses were more challenging, as they needed to be visually convincing. The conservators used a synthetic, thermoplastic material which could reactivate with a heated spatula to adhere it in position. They added texture to it like leather, and stamped it to match the existing decorative punchwork. Finally, they applied metal leaf and glazes to color the areas to match.

At the end of treatment, both stools were more like the glittering jewels that Isabella Stewart Gardner envisioned for her Long Gallery. Come find them next time you join us at the Museum!

You May Also Like

Restoring Bardini Blue in the Long Gallery

Read More on the Blog

Preserving Our Colorful History: The Soisson Window

Read More on the Blog

1Trench, Lucy ed. 2000. Materials & Techniques in the Decorative Arts: An illustrated Dictionary. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.