In the Blue Room of the historic Palace hangs an unassuming and unfinished oil sketch. It is simply called A She-Goat. Laying on her side, we see the varying textures of this goat’s coat—rougher and darker on top with a soft underbelly—and a glimmer in her eyes offset by touches of pink paint. While the goat is definitely adorable and beautifully rendered, this creature is perhaps most interesting because of the artist who painted her: Rosa Bonheur (1822–1899).

Rosa Bonheur (French, 1822–1899), A She-Goat, 19th century. Oil on canvas

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. See it in the Blue Room

Bonheur was one of the most successful painters in France during the second half of the nineteenth century. It was relatively rare for women to become professional artists at the time. However, Bonheur’s father, Raymond, was a painter and trained all of his children to be artists, regardless of their gender. Bonheur was best known for her images of rural French life, particularly animals—like the goat at the Gardner.

Bonheur’s first work to receive significant critical acclaim and public attention was Ploughing in the Nivernais (1849), which won a first-class medal when it debuted at the Paris Salon—the most important exhibition of contemporary art in nineteenth-century France. From there, a series of major successes defined Bonheur’s career: she sold mammoth works like The Horse Fair for astronomical prices (in this case to American shipping magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt) and was the first woman artist awarded the Legion of Honor, France’s highest order of merit.

For all these traditional markers of artistic acclaim, Bonheur’s life was anything but typical. For example, she preferred to wear pants—then exclusively a garment worn by men—instead of dresses. This was technically illegal in mid-nineteenth century France, so she received special “cross-dressing permits” from the government. Officially, she was granted a license to wear pants because she argued men’s clothing made it easier for her to visit farms and paint animals. The decision was, however, likely driven by more than just practicality.

Official “cross-dressing permit” issued to Bonheur's longtime partner, Nathalie Micas; a similar permit was granted to Bonheur.

Courtesy of Château Rosa Bonheur. Photo: Claudine Doury

She challenged traditional gender roles and expectations in a number of ways, including maintaining long-term relationships with two women. First, for decades, she lived with another French painter, Nathalie Micas. They cohabited at the Château de By outside of Paris, recently converted into a museum celebrating Bonheur’s life and career.

After Micas passed away in 1889, Bonheur met the American painter Anna Klumpke. While their first meeting was brief, they reconnected when Klumpke painted Bonheur’s portrait. The American was 34 years younger than her French counterpart, but the two hit it off. They decided to combine their lives and, in their own words form “the divine marriage of two souls” and announced their intentions—including the logistical practicalities of each contributing to the relationship by “working hard to earn [her own] living”—to Klumpke’s family.1

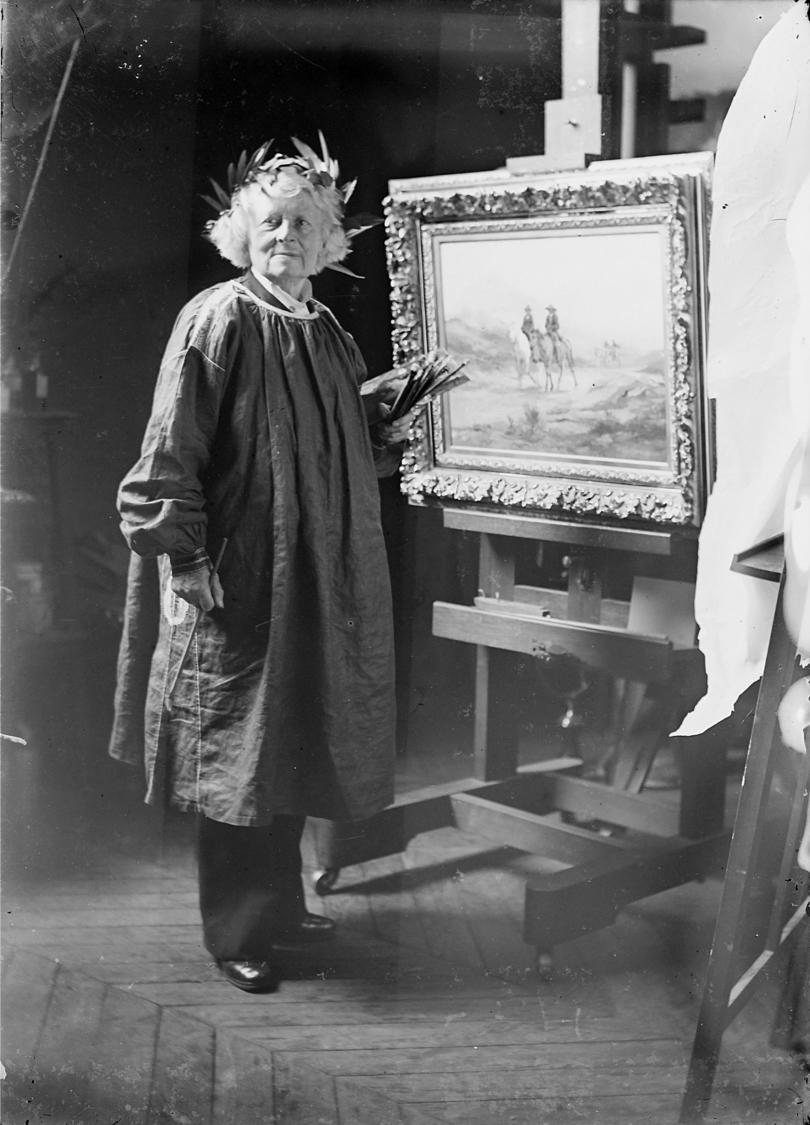

Anna Klumpke (left) and Rosa Bonheur (right)

Courtesy of Château Rosa Bonheur

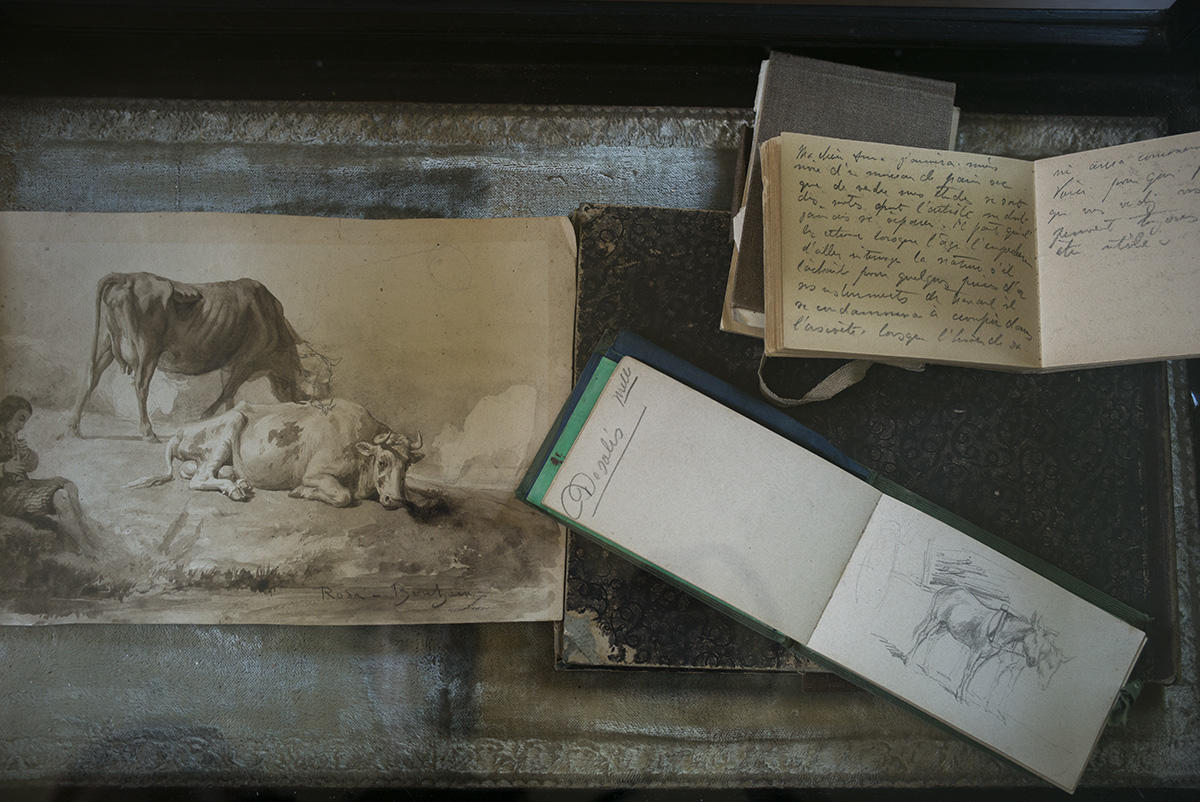

When Bonheur died in 1899, Klumpke inherited most of her property. The American then dedicated herself to memorializing Bonheur and celebrating her career, including organizing a sale of works remaining in the artist’s studio—the same sale where Isabella likely bought the She-Goat.

1Anna Klumpke, Rosa Bonheur: Sa Vie, Son Oeuvre, p. 110-12

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

Sarah Wyman Whitman: Artist and Advocate

Explore the Museum

Visit the Blue Room

Buy a Print

Rosa Bonheur (French, 1822–1899), A She-Goat, 19th century