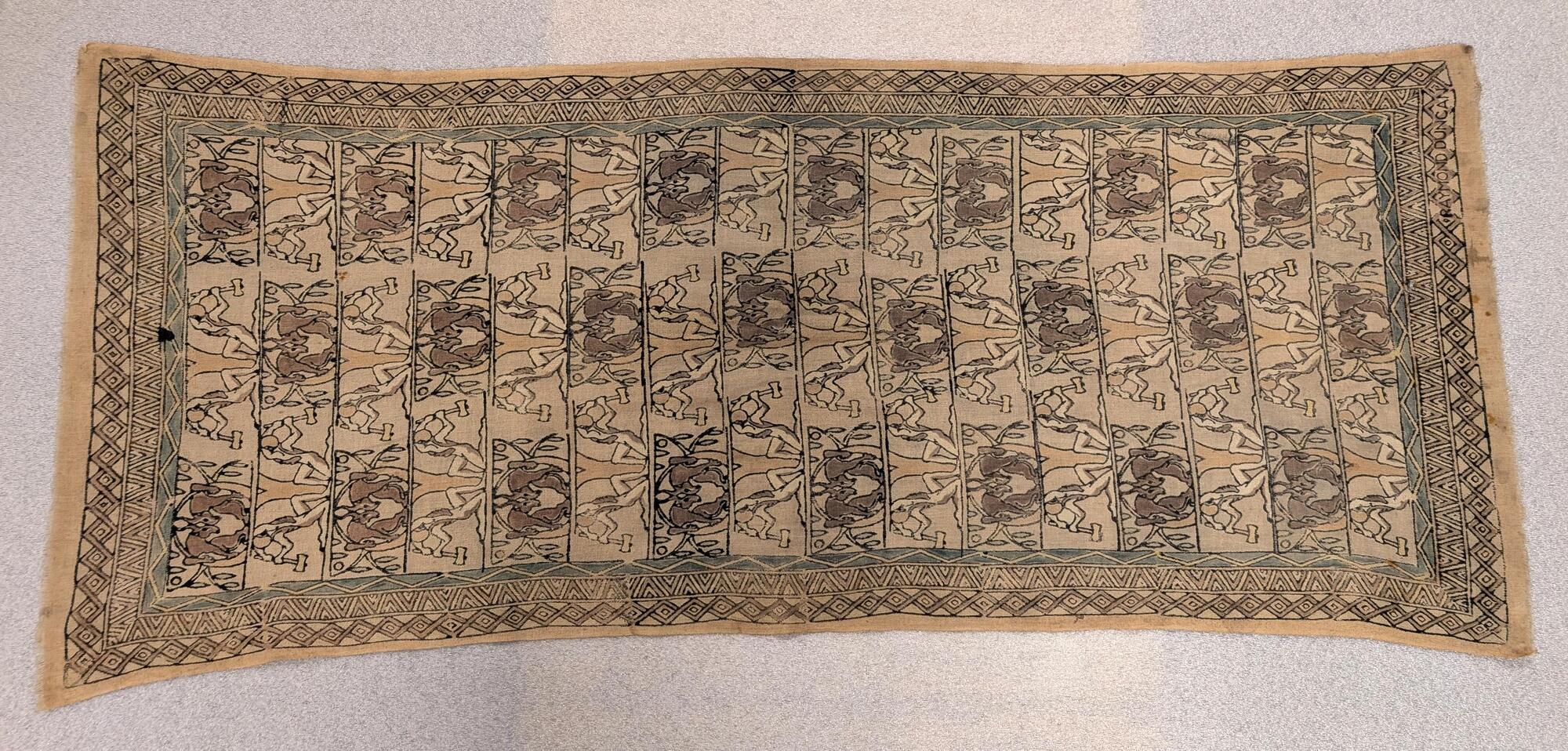

The Tapestry Room features a block printed silk square made by Raymond Duncan and given to Isabella Stewart Gardner by her friend, the painter Louis Kronberg (1872–1965) in 1921. Although it dates to the early twentieth century, the subdued vegetable-dyed silk is complementary to the colors of the fifteenth-century Flemish tapestries throughout the space. A closer look at the object reveals a fascinating offshoot of the aesthetic movement of the late 1800s, which advocated for “art for art’s sake,” emphasizing beauty and pure form over moralizing messages in artworks. This manifested across Europe and the United States in different ways related to art, design, theater, and even informed the ways people lived and worked in artistic communities. Duncan’s particular version of an aesthetic approach involved engaging with and embodying ancient Greek ideals.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (T19w24)

Raymond Duncan (American, 1874–1967), Scarf with Design of Tree Trunks, about 1919. Printed and painted silk tabby , 60 x 57 cm (23 1/2 x 22 1/2 in.) A reproduction of the scarf is displayed in the Tapestry Room of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

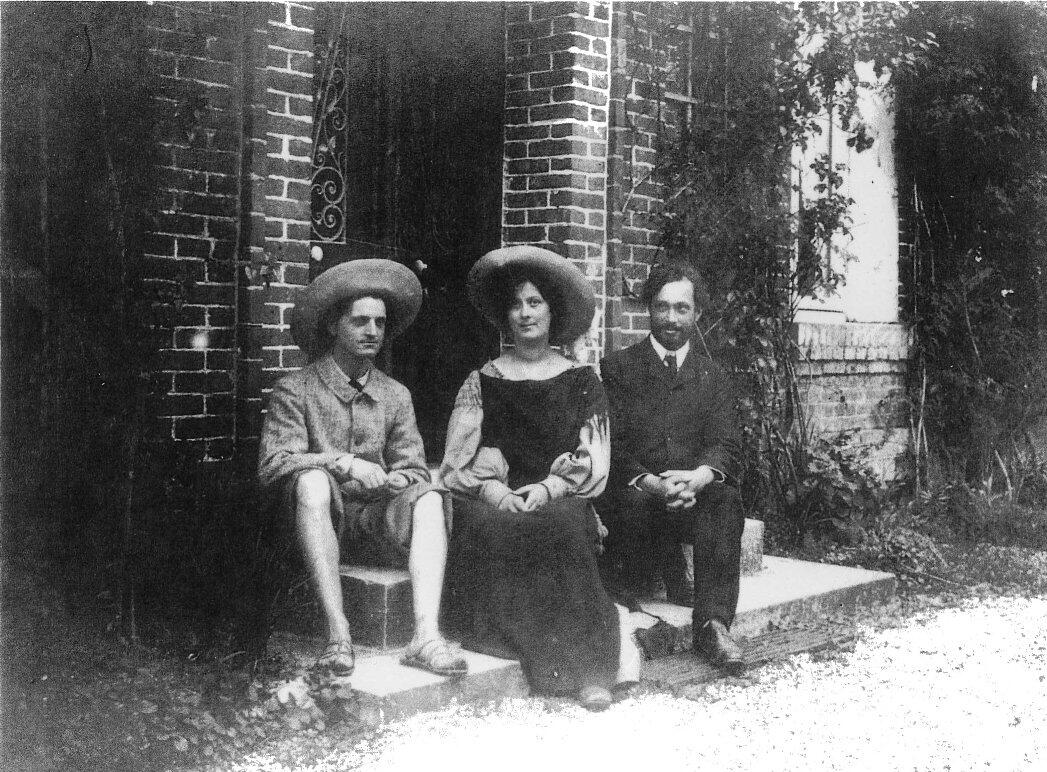

The scarf was created at the Parisian workshop of Raymond Duncan (1874–1966), elder brother to Isadora Duncan (1877–1927), remembered for her contributions to early modern dance, and her tragic death in the South of France when her scarf (not believed to be one created by Duncan) became ensnared in the wheel of the vehicle she was riding in. A definitively bohemian family, the Duncans all recited poetry, participated in theater productions, danced, and created other forms of performance art. The two youngest siblings of the family, Raymond and Isadora were always close. They also shared a romanticized appreciation for Greek art and culture, one source of inspiration for adherents of the aesthetic movement. They traveled as young adults with their two older siblings and mother at the turn of the century, leaving their native California first for New York, then London, Paris and, finally, Greece.

Photo from the Duncan collection, courtesy of Anne-Marie Sandrini; http://www.les-petites-dalles.org/

Raymond, Isadora, and Augustin Duncan, before their departure for Greece in 1903

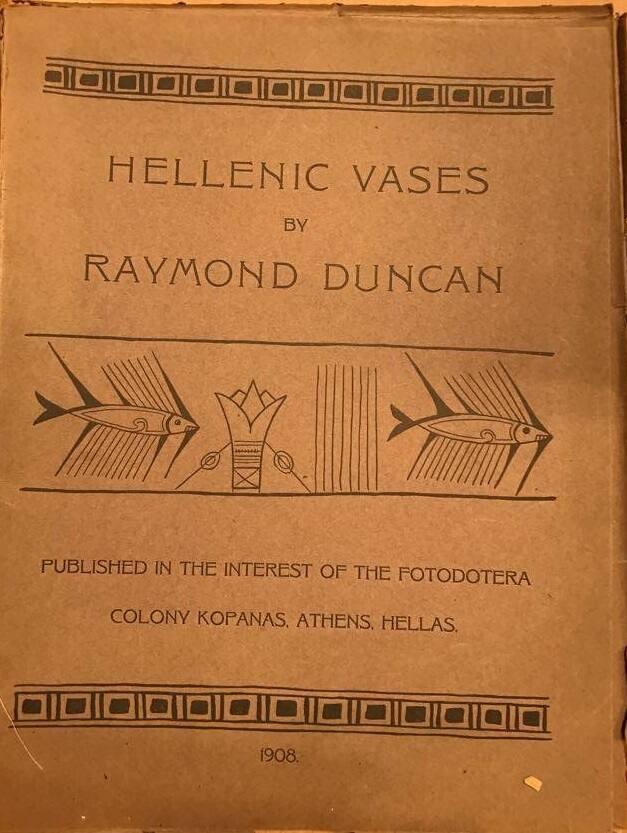

In London, the pair studied ancient Greek vases and bas reliefs at the British Museum. While living in Paris, they continued their surveys at the Louvre, with Raymond copying the iconography and Isadora incorporating the poses into her dance movements. When the family arrived in Greece in 1903, apparently by boat following a route that emulated Odysseus’ journey in the Odyssey, they attempted to create a family compound and dancing school on an arid hilltop they purchased and called “Kopanos.” Once there, Raymond abandoned his Oscar-Wilde-inspired wardrobe for an approximation of what the ancient Greeks wore: a tunic, shawl, and sandals. He would go on to wear this uniform for the rest of his life, another sixty-six years.

The U.S. National Archives

Raymond Duncan, Paris, 1948–57

After Raymond met and married his Greek wife, Penelope Sikelianos (1883? –1917), around 1904, the young couple traveled around Europe and later to the United States. They attracted a significant amount of press attention for their unusual dress. Raymond learned to seize on this sartorial fascination to promote his performance, philosophy, and the textiles he designed and sold.

The production of Duncan’s textiles was unique. They were made in “Akademias” that he founded. The Akademias were communes where members dressed in Greek-inspired clothing, ate and prepared vegetarian food, performed poetry, dance, and theater, and even raised goats. The first early iterations of these communities was on the Greek mountain top, Kopanos. However, by 1911 they had founded another community in Paris, followed by another in Albania to welcome refugees from the First Balkan War (1912–13). Ultimately, the Parisian Akademia—which moved several times in its history—became the only surviving community, occupying prime real estate in Paris’ 1st Arrondissement from 1929 until the 1970s.

Penelope taught Raymond to weave, and they soon incorporated weaving into the life of the Akademias. Weaving textiles not only produced clothing for the community, but they could then sell their work to earn money to support the Akademias. Raymond brought his own particular twist to this textile production. As a boy, he worked at printing presses that produced newspapers. He adapted this learning both to publish his writings, and to use block printing to decorate the handwoven silk scarves made by the members of the Akademia. According to accounts written by former Akademia members, printing and hand painting the textiles was an expected activity for earning one’s keep at the centers.

Isabella Stewart Gardner’s scarf is one of these hand-woven block-printed pieces.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (T19w24). A reproduction of the scarf is displayed in the Tapestry Room of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

Raymond Duncan (American, 1874–1967), Scarf with Design of Tree Trunks, about 1919. Printed and painted silk tabby , 60 x 57 cm (23 1/2 x 22 1/2 in.)

Other examples of Raymond Duncan-signed block printed pieces exist in different museum collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Most of these date to the 1920s, and it is possible to spot the reoccurring blocks used on these textiles; for example the interlaced diamond border apparent on the Gardner piece appears on a larger silk scarf in the collection of the Art Institute, and again on a smaller wool and cotton table scarf in the collection of the Oakland Museum of California. The block printing and hand painting are inconsistent in quality, a sign of the many hands of the Akademia and their differing levels of skill.

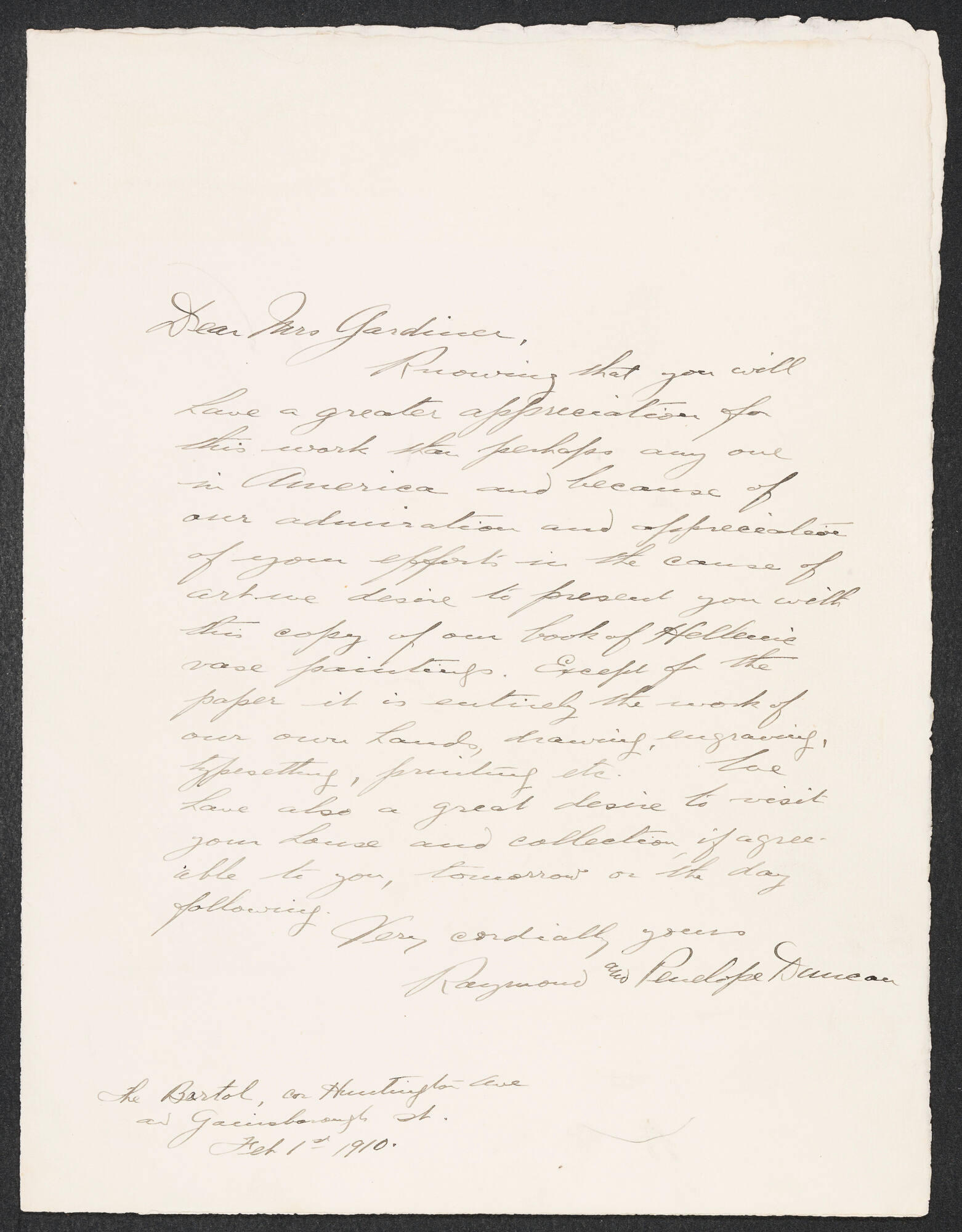

Nearly a decade before Kronberg gave Isabella her scarf, Raymond and his wife, Penelope were eager to catch Gardner’s attention when they traveled to the United States in February 1910. They left her a note, presenting one of Raymond’s early self-published pamphlets and observing that she would “have a greater appreciation of this work than perhaps anyone in America.” The couple concluded by politely inviting themselves over to “visit your house and collections.” While it is unclear whether Isabella welcomed the Duncans, who were in Boston promoting a series of Greek performances, the pamphlet and their note remain in the Gardner’s archives.

The fact that Gardner specifically chose to display a Duncan scarf in her Tapestry Room may demonstrate her appreciation for a fascinating man who—not unlike the museum founder—sought to create spaces for community and idyllic beauty in the world.

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

Henry Mercer’s Moravian Pottery and Tile Works at Fenway Court

Read More on the Blog

Silk Shopping in the South of France

Read More on the Blog

Sarah Wyman Whitman: Artist and Advocate

Further Reading

Bonney, Therese, and Louise Bonney. 1929. A Shopping Guide to Paris. R.M. McBride & Co.

Bowman, Sara, and Michael Molinare. 1985. A Fashion for Extravagance: Art Deco Fabrics and Fashions. E.P. Dutton

Desti, Mary. 1929. The Untold Story: The Life of Isadora Duncan 1921-1927. Horace Liveright

Duncan, Isadora. 1927. My Life. Boni and Liveright

Martinelli, Megan. 2013. “‘Would Live Like Ancient Greeks’: The Art and Life of Raymond Duncan.” University of Rhode Island. https://doi.org/10.23860/thesis-martinelli-megan-2013

McAlmon, Robert, and Kay Boyle. 1968. Being Geniuses Together. Doubleday & Company, Inc.

Niklas, Charlotte, and Annebella Pollen, eds. 2015. “‘At Once Classical and Modern’: Raymond Duncan Dress and Textiles in the Royal Ontario Museum.” In Dress History: New Directions in Theory and Practice, 1st ed., with Alexandra Palmer. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Roatcap, Adela Spindler. 1991. Raymond Duncan: Printer, Expatriate, Artist. Book Club of California.

Splatt, Cynthia. 1993. Life Into Art: Isadora Duncan and Her World. Edited by Doree Duncan, Carol Pratl, and Cynthia Splatt. W.W. Norton & Co.