Just as Turkey is situated on the border between Europe and Asia, this Turkish tile in the Gardner Museum’s collection sits in a window between the Italian-inspired Courtyard and the Spanish Cloister, which holds exquisite art pieces from both the Hispanic and Islamic world. But the Turkish tile stands out, and for good reason.

The Origin of Turkish Tiles

The tile was manufactured around 1575 in the town of İznik, located in Western Turkey, during the height of high-quality tile production in that region. Many of the tiles produced in İznik during the mid to late 16th century decorated important public buildings constructed during the Ottoman Empire. The most common were palaces and mosques, although some tiles appeared in domestic secular settings. Some İznik tiles came in sets that, when placed together, created repeating patterns on the walls of the buildings they adorned.

The Turkish tile in the Spanish Cloister

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Interestingly, these tiles are not made from traditional clay but from a material called fritware or stonepaste. Fritware is a mixture of ground up quartz, white clay and frit (a fine glassy powder). This material was likely invented in 11th century Egypt in an attempt to replicate Chinese porcelain. Fritware technology spread from Egypt throughout other Islamic lands and was the dominant type of ceramic for centuries.

The Unique Tile of the Gardner

The Gardner Museum’s tile depicts a central grape leaf (Vitis is its scientific name in Latin) on a meandering vine surrounded by immature grape clusters.

Turkish, Iznik, Tile, about 1575. Glazed ceramic, 21.5 x 25 cm (8 7/16 x 9 13/16 in.)

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (C7w3). See it in the Spanish Cloister.

Jenny Pore, Museum Horticulturist, helped identify the flowers and leaves on the tile: tulips (Tulipa), carnation petals (Dianthus caryophyllus), serrated saz leaf (reed), rose leaves (Rosa), hyacinth (Hyacinthus) and wild or common hyacinth (Hyacinthus orientalis). The design of the tile has a repeating pattern that is unusual for Iznik tiles, but has the quintessential İznik color palette of blue, turquoise, green, red, and black on a white slip ground. A thick, clear glaze coats these colors, saturating and protecting their vibrancy.

The botanical motifs on the Turkish tile: 1. Grape leaf (Vitis) 2. Tulips (Tulipa) 3. Carnation petals (Dianthus caryophyllus) 4. Serrated saz leaf (reed), 5. Rose leaves (Rosa) 6. Hyacinth (Hyachinthus) 7. Wild or common hyacinth (Hyacinthus orientalis)

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Flowers identified by Jenny Pore, Museum Horticulturist

Analyzing the Turkish Tile

In order to learn more about the glaze colorants, we analyzed tile with portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF) spectroscopy.

Conservator Jessica Chloros analyzing the Turkish tile with portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF) spectroscopy, 2022

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

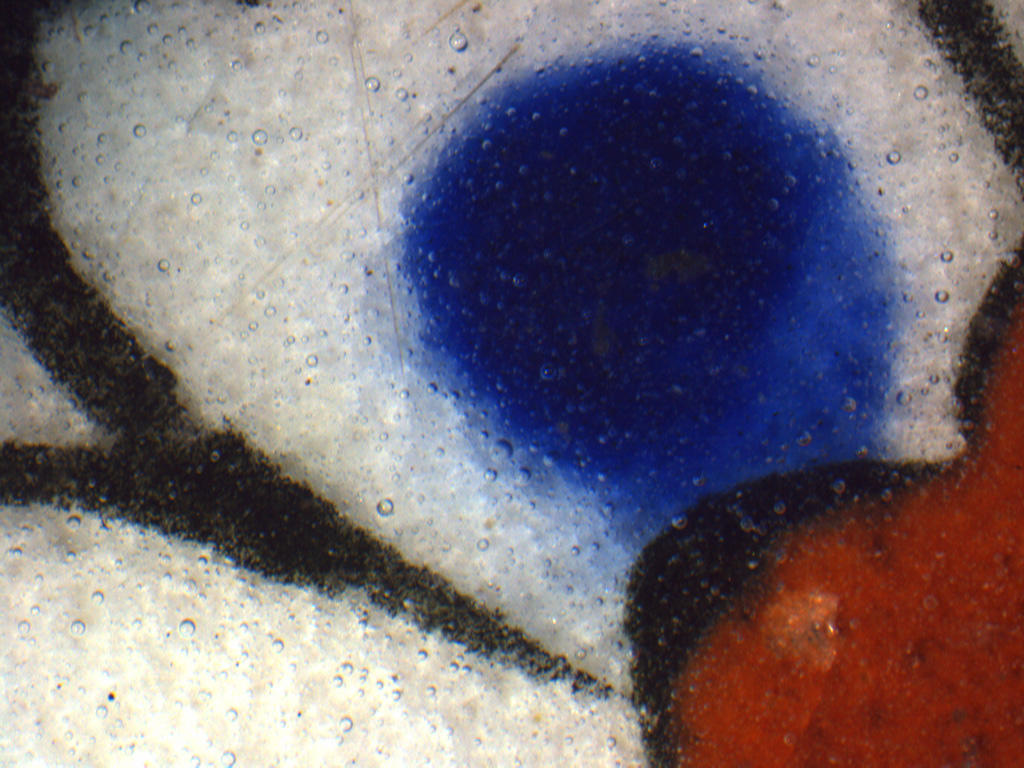

pXRF is a fast, non-destructive form of analysis that detects the elements that are present in a particular area; almost like an elemental fingerprint for materials. For instance, pXRF analysis revealed that the dark blue glaze colorant contains cobalt (cobalt oxide) while the turquoise glaze contains copper (cupric oxide) oxide. We also used the magnification of a stereobinocular microscope to observe the tile. Images from that exercise in close-looking show the detailed application of areas with multiple glaze colors and the way that the colors partially diffuse into the thick, bubbly clear glaze layer on top.

The Turkish Tile’s Twin

We don’t know who designed our tile or for what location, but we do know that there is another tile of the same unusual design. It resides in the collection of the members-only Providence Art Club in Providence, Rhode Island. What are the odds that two of the very few tiles known for this pattern would end up 5,000 miles away from where they were created, and only 50 miles apart from each other?

Next time you are in Boston, make sure to visit the Gardner Museum to see the only one of these beautiful and unique tiles on display in a public collection.

You May Also Like

Turkish, Iznik, <em>Plate</em>, about 1650-1699

Explore the Collection

Turkish, Kutahya, <em>Pitcher</em>, 18th century

Explore the Collection

Oriental and Islamic Art at ISGM

Buy a Book