Though best-known for its oil paintings and sculptures, the Gardner Museum has many photographs in its collection. These photographs were created with a wide-range of photographic methods, including three daguerreotypes.

The daguerreotype is an early photograph and one of the first truly viable methods of permanently capturing an image. Invented by French artist and photographer Louis Daguerre, the daguerreotype was first introduced to the French Academy of Sciences in Paris on August 19, 1839. Its popularity immediately spread throughout the world and persisted until the late 1850s when other faster and less expensive processes became available.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

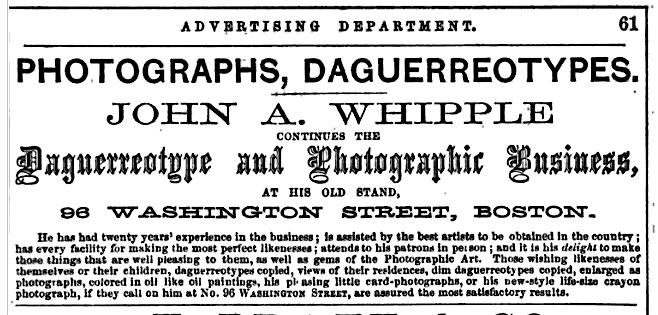

One of the first cities to embrace this revolutionary technology was Boston. In the spring of 1840, just months after its inauguration (and the same year Isabella Stewart Gardner was born), the Massachusetts Historical Society hosted a demonstration of the daguerreotype process. By 1850, there were dozens of daguerreotypists who set up shop in the city, including the renowned Albert S. Southworth and Josiah J. Hawes (a.k.a. Southworth and Hawes), Lorenzo Chase, and John Whipple.

How Do Daguerreotypes Work?

Daguerreotypes technically exhibit a negative image, but appear positive because of the way the image particles scatter light at certain viewing angles. The daguerreotype image is made up of silver mercury amalgam particles on a highly polished silver plated sheet of copper that appears almost mirror-like. Soon after its invention, French physicist Armand Hippolyte Louis Fizeau contributed the step of gilding, otherwise known as gold toning, to the daguerreotype process, as it imparts more image contrast and physically more robust image particles. The daguerreotype is a unique object and considered a “direct positive” in the sense that there is no “negative” from which to make multiple copies. As seen in this elegant presentation of the process by The Daguerreobase Project and the Museo FirST - Firenze Scienza e Tecnica, the daguerreotype plate is the sole carrier of the image and is placed directly in the camera during its light-sensitive state.

The Gardner Daguerreotypes

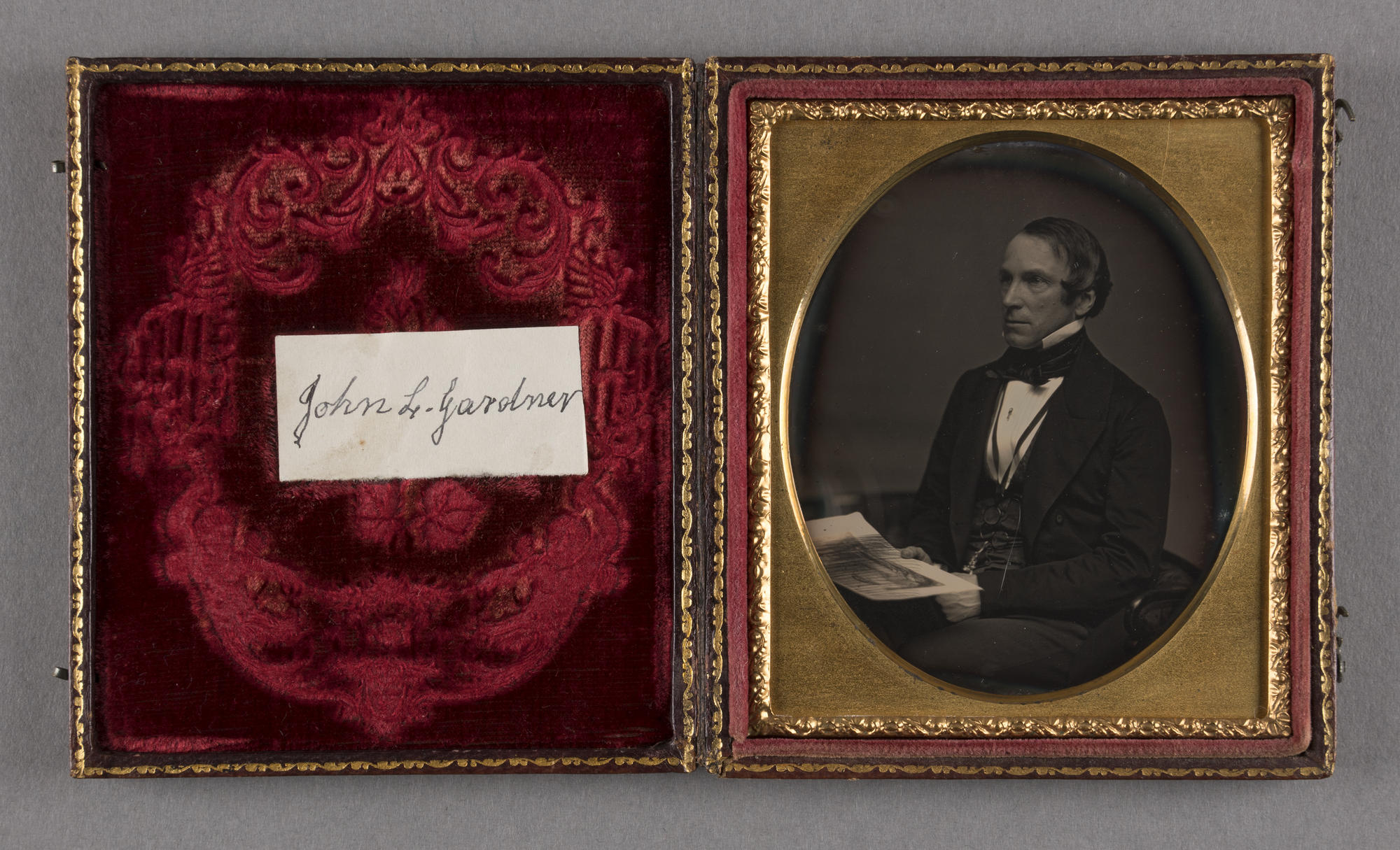

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum’s collection and archive hold three daguerreotypes of the Gardner family: Isabella’s sister-in-law (and matchmaker) Julia Gardner as a child, father-in-law John Lowell Gardner, Sr., and husband John Lowell Gardner, Jr. as a child. Two of the three daguerreotypes have unknown makers. However, a lot can be garnered through close examination of the daguerreotypes’ different components

Illustration courtesy of the Graphics Atlas

Parts of a cased daguerreotype

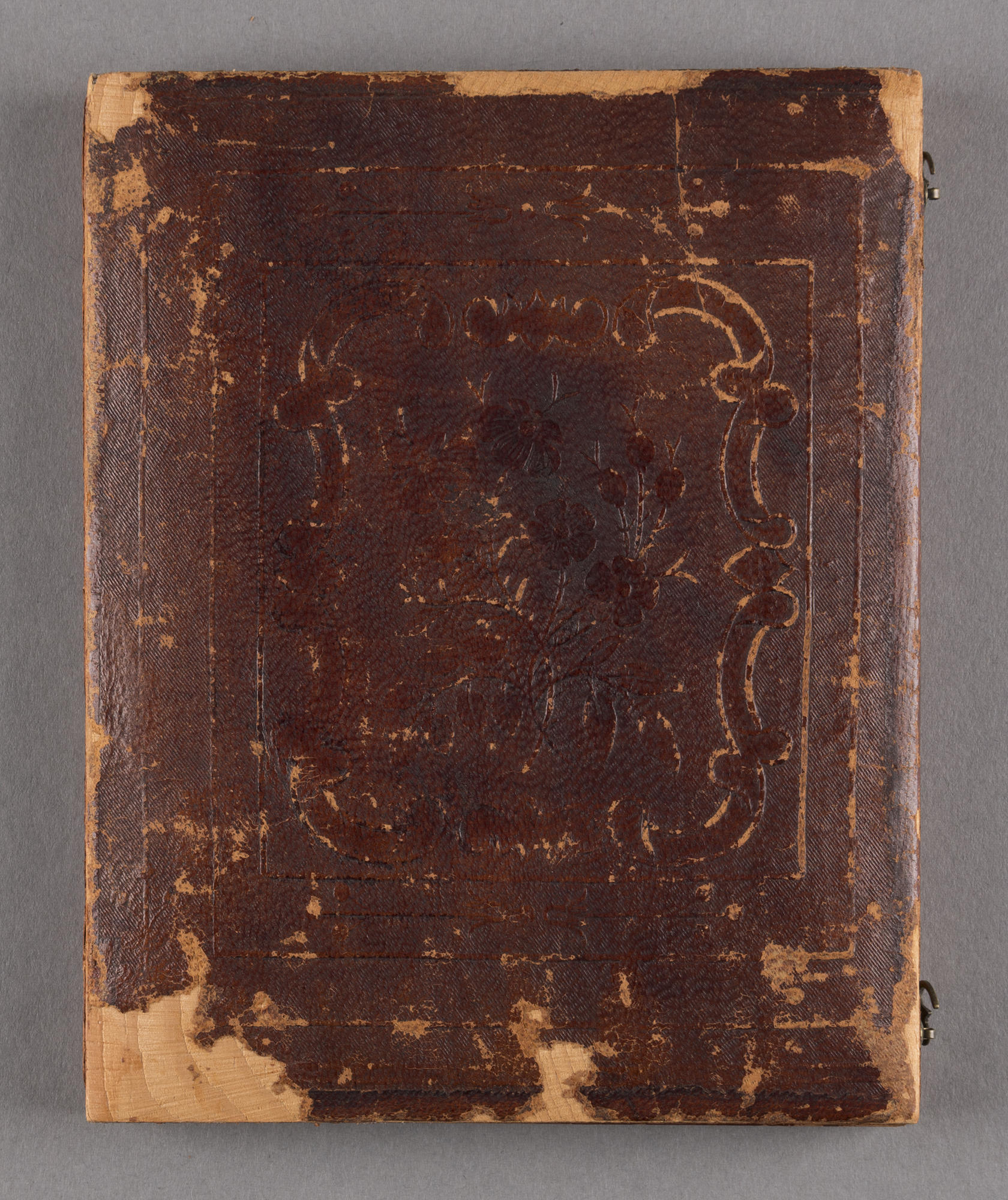

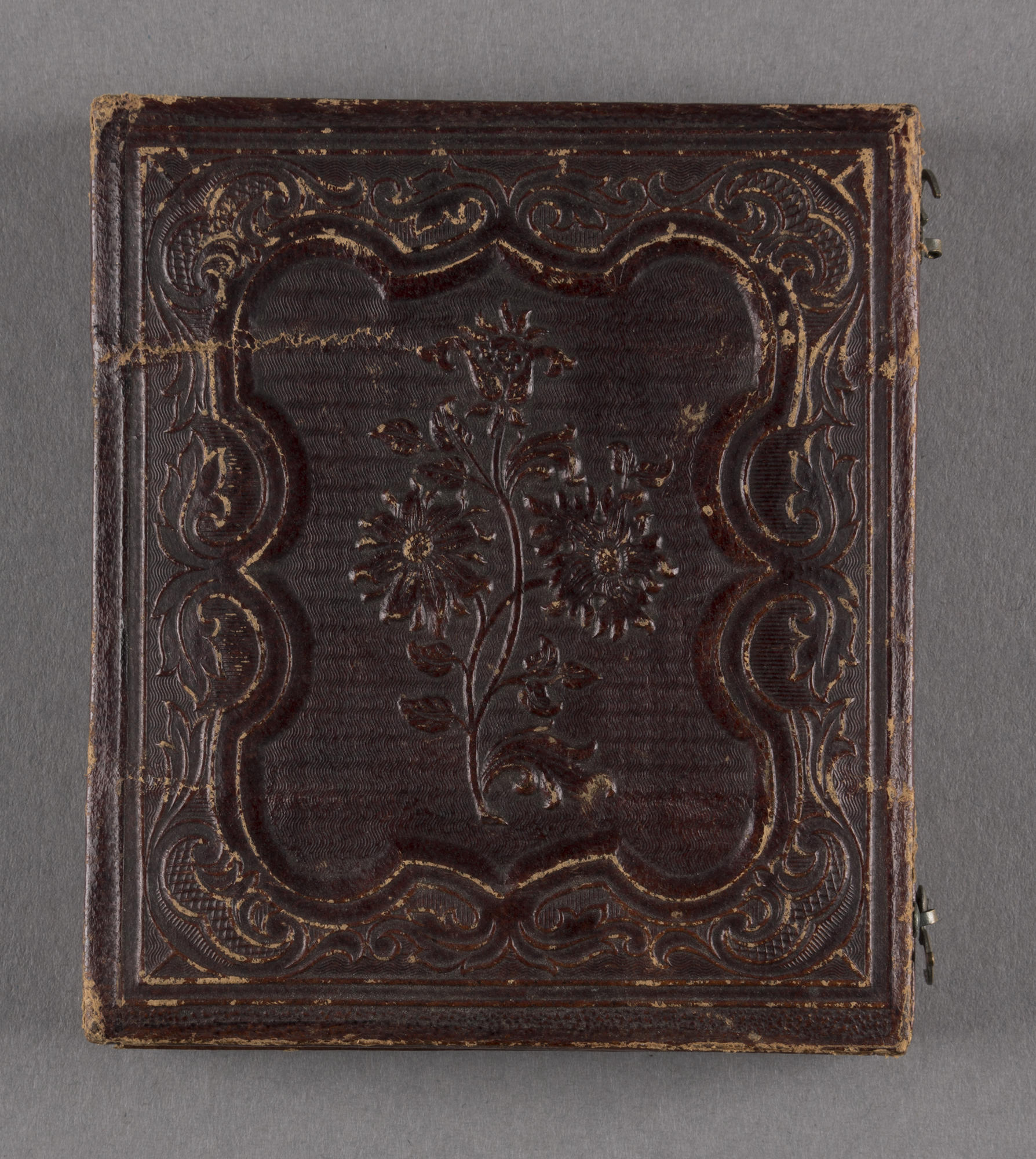

The daguerreotype of Julia does not have a preserver, the copper alloy foil that wraps around the edge of the daguerreotype package, and it has a brass mat with a simple oval window. These characteristics were more common in British and early American daguerreotypes. Its simple daguerreotype case made of wood covered with embossed leather was also commonly found with American and British daguerreotypes. The tape that once bound the daguerreotype package together is intact, suggesting that the package had never been opened and its glass and brass mat are original.

The daguerreotypes of John Sr. and Jr. also have wooden cases covered with embossed or plain leather, and simple brass mats with oval windows.

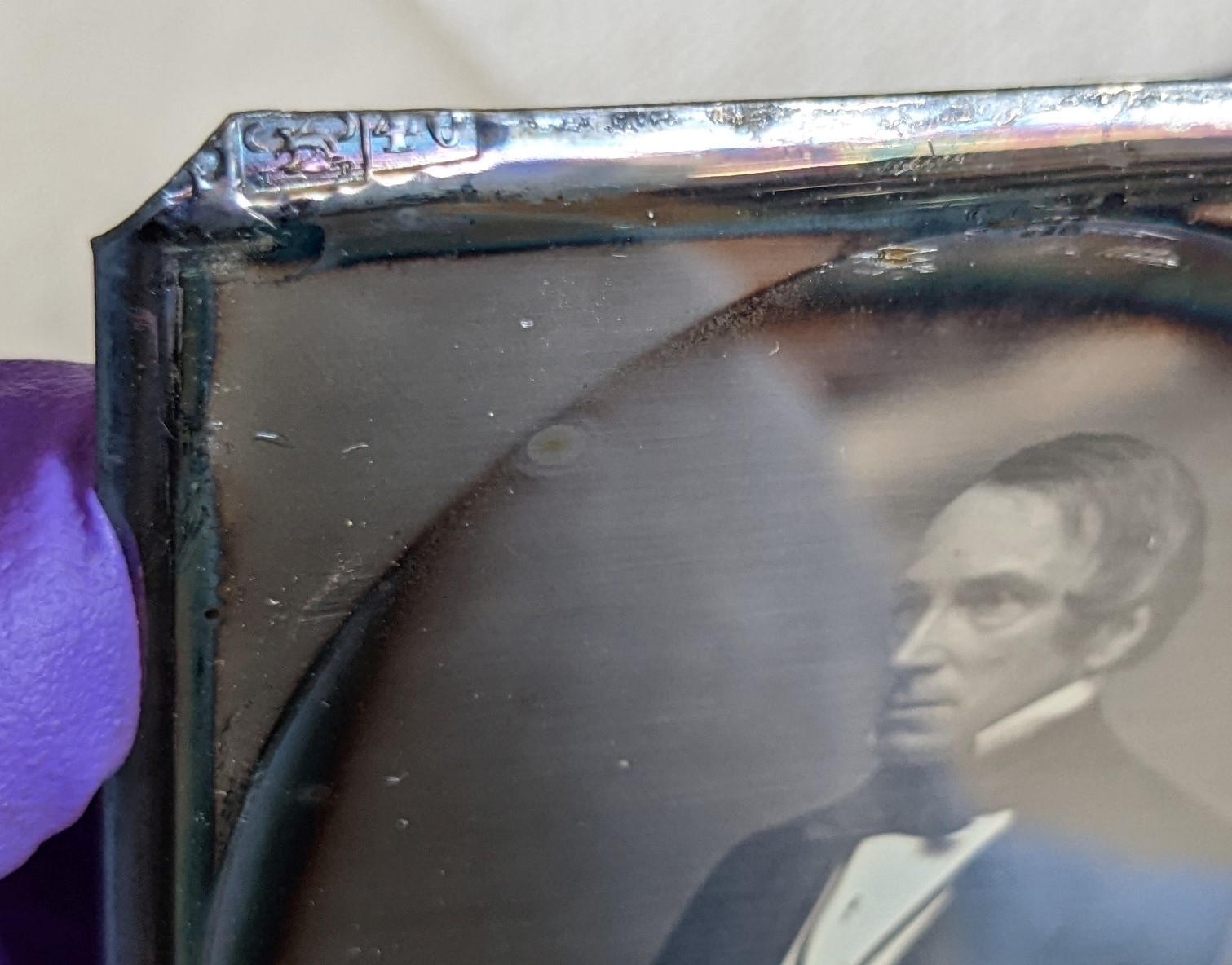

The brass mat of John Jr.’s portrait has the photographer’s name, (John) Whipple, embossed in the lower left corner, and both daguerreotypes have the same hallmarks stamped along their edges, which identify the daguerreotype plate manufacturer or supply house and its ratio of silver to copper. Their hallmarks are that of a French manufacturer whose name is unknown but is described as a Six Petal Flower - Doublé/Pascal Lamb/J.P. (all within a rectangle) – 40 (within a rectangle).¹ The number 40 signifies a plate metal ratio of 1 part silver to 39 parts copper. This particular daguerreotype plate is documented to have been used from 1850 to 1858, with peak years of 1854 to 1856. It was among the most common plates used by Southworth and Hawes, and likely the second most widely used French plates.

These exquisitely detailed photographs have a high resolution unrivaled by any other photography technique available around the turn of the 19th century. Sometimes poetically referred to as mirrors with a memory, part of what makes these images so enchanting is that the image that you see is a direct link to the light that formed it nearly 200 years ago. Furthermore, the cases that house them document the numerous times these objects were looked at, held close, and possibly traveled as precious heirlooms. With the continued stewardship of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, these beautiful specimens and connection to Isabella’s family history will live on.

You May Also Like

Buy Book

Isabella Stewart Gardner: A Life

Learn More About Isabella

An Unconventional Life

Read More on the Blog

Overlooked Female Photographer, Clover Adams

¹ The same, yet complete, hallmark listed in the Daguerreotype Portal.