Cafe G is closed for repairs from January 29 through February 16, 2026.

We apologize for the inconvenience.

In the Gardner Museum’s portrait of Madame Auguste Manet, Édouard Manet shows his mother Eugénie-Désirée Fournier (1811–1885) dressed in widow’s black. Manet’s father had passed away on September 25, 1862. The fact that she wears some simple gold jewelry and the veil is behind her head rather than covering her face, allows the viewer to surmise that at least a year had passed since his death. During the first year of mourning for widows, face and hair were to be covered, and no jewelry was to be worn; during the next six months, pieces made of jet were permissible. Eugénie’s black belt buckle typifies the jet accessories worn by widows in the second year of mourning. Her black dress, with its hint of sheen and its understated trim, also signals mourning after the first six months, as shinier fabrics would have been avoided. The dress otherwise exemplifies the fashions of the 1860s, with its sloping shoulder, high waist, and full skirt.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P3s4). See it in the special exhibition “Manet: A Model Family,” on view in Hostetter Gallery, October 10, 2024–January 20, 2025 or in the Blue Room.

Édouard Manet (French, 1832–1883), Madame Auguste Manet, about 1866. Oil on canvas, 98 x 80 cm (38 9/16 x 31 1/2 in.)

The arresting gaze of Madame Auguste Manet is one of the painting’s most forceful elements. Her figure is life size, and Manet silhouettes the light color of her face and hands against her black dress, black veil, and dark background. Her expression resembles the one she displayed in a carte-de-visite portrait in an album belonging to Édouard Manet; the photograph had probably been taken a few years earlier.

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris

Charles Amédée Barenne, Eugénie-Désirée Fournier (Madame Auguste Manet), from Album of Cartes-de-Visite Portraits Belonging to Édouard Manet, about 1857–62. Carte-de-visite, 9.2 x 5.6 cm (3 ⅝ x 2 ⅛ in.)

The subtle turn of her head, the straight line of her lips, the softness of an older woman’s jawline, all are quite similar between painting and photograph. Yet, the expression that might be described as pensive in the carte-de-visite, lightened by the slight overexposure of the face in relation to the black velvet dress worn in the photograph, takes on more gravitas in Manet’s imposing painting. Manet’s painterly handling of every facial feature—the creases at the corners of her mouth, the cleft in her chin, the arch of her eyebrows, and the emphatic shadows around her eyelids—not only accentuates shadows that are minimized in the photograph but also emphasizes the fleshliness of the sitter.

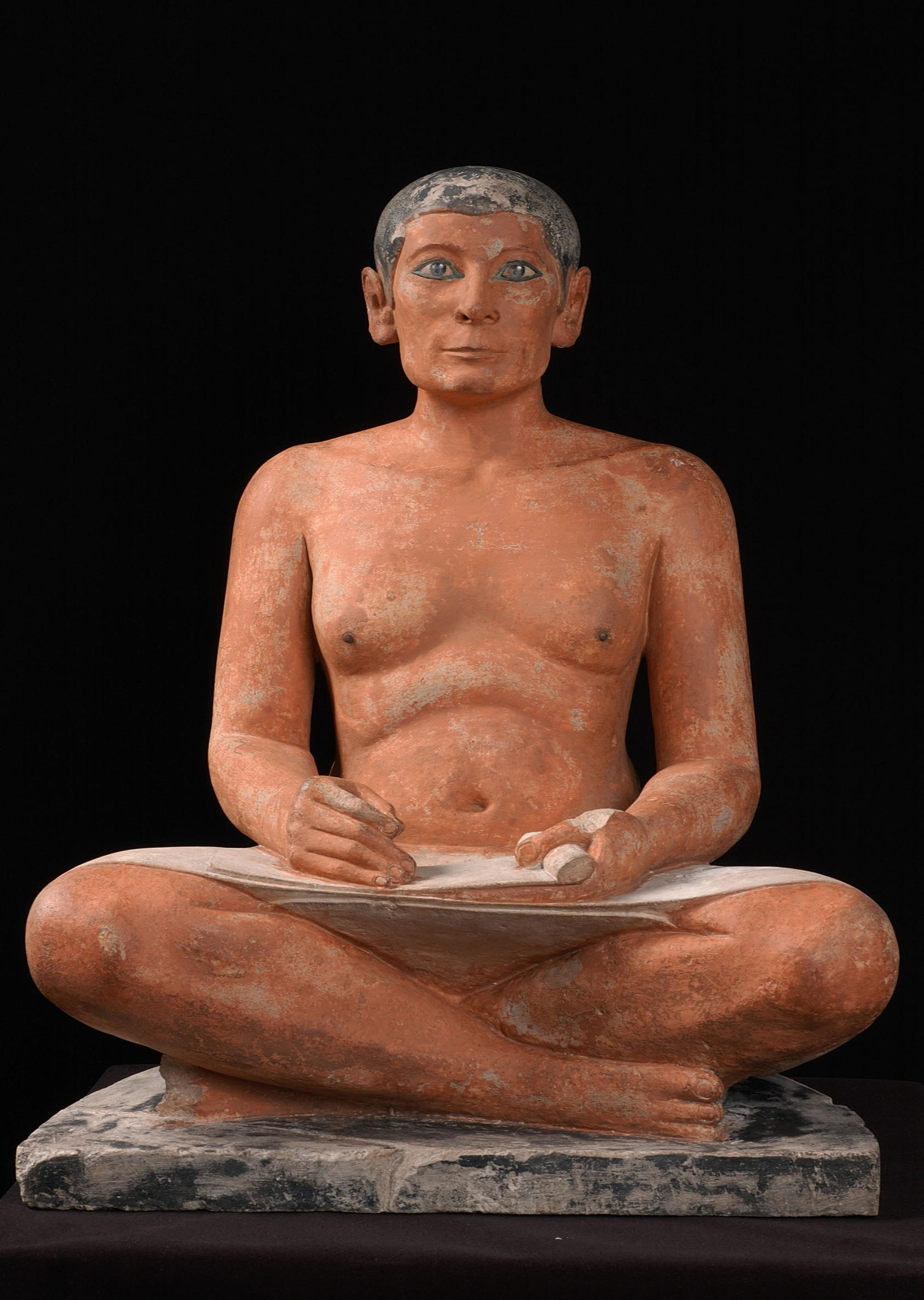

No wonder art historian Bernard Berenson, who purchased the painting on behalf of Isabella Stewart Gardner in 1910, wrote to her, the “drawing is of the surest, the touch most vigorous,” and compared it to the Seated Scribe in the Louvre, an Old Kingdom ancient Egyptian sculpture of a figure with a similarly serious expression, hands in lap. Berenson’s comparison of Manet’s oil painting to an ancient sculpture of the somber scribe might accentuate the starkness of each, but it also brought home the indelible modernity of Manet’s figure.

Musée du Louvre, Paris

Egyptian, Saqqara-Nord, Seated Scribe, 2620–2500 BCE. Limestone with alabaster, rock crystal, and copper, 53.7 x 44 x 35 cm ( 21 1/16 x 17 ⅜ x 13 ¾ in.)

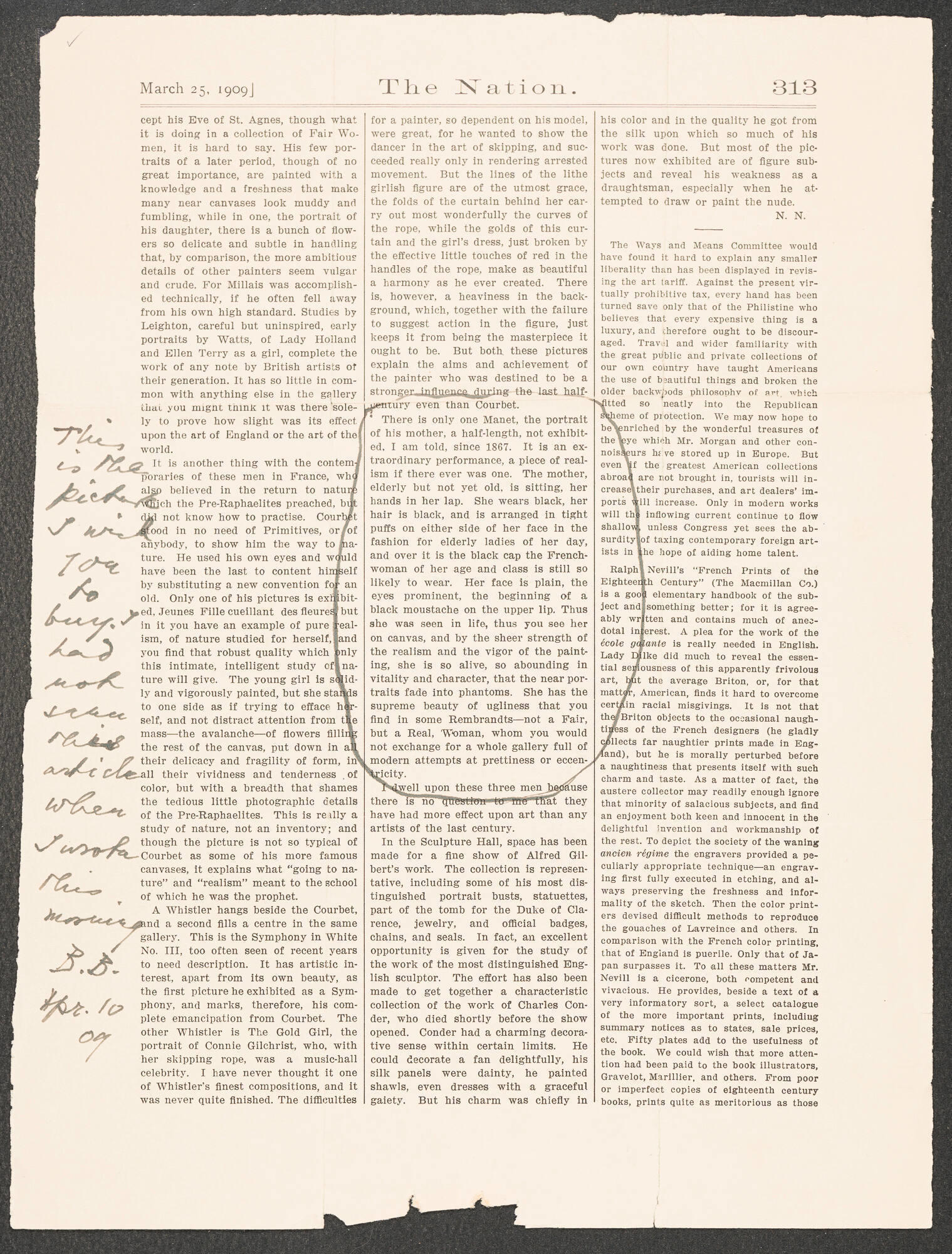

Gardner had been interested in acquiring a painting by Manet, and the museum’s archives include an article describing the portrait of Manet’s mother that Berenson had clipped and sent to Gardner. The article from The Nation describes an exhibition in February and March of 1909 called “Fair Women,” held at the Royal Academy (the New Gallery, 121 Regent Street, London).

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.010414)

Elizabeth R. Pennell (American, 1855–1936), “Art: A Show of Fair Women,” Nation 88, March 25, 1909, no. 2282, p. 313, with Bernard Berenson’s note to Isabella Stewart Gardner

In it, there is both a straightforwardness and a thoroughness about the description of Manet’s painting. The Nation’s critic in London wrote:

There is only one Manet, the portrait of his mother, a half-length, not exhibited, I am told, since 1867. It is an extraordinary performance, a piece of realism if there ever was one. The mother, elderly but not yet old, is sitting, her hands in her lap. She wears black, her hair is black, and is arranged in tight puffs on either side of her face in the fashion for elderly ladies of her day, and over it is the black cap the Frenchwoman of her age and class is still so likely to wear. Her face is plain, the eyes prominent, the beginning of a black moustache on the upper lip. Thus she was seen in life, thus you see her on canvas, and by the sheer strength of the realism and the vigor of the painting, she is so alive, so abounding in vitality and character, that the near portraits fade into phantoms. She has the supreme beauty of ugliness that you find in some Rembrandts—not a Fair, but a Real, Woman, whom you would not exchange for a whole gallery full of modern attempts at prettiness or eccentricity.

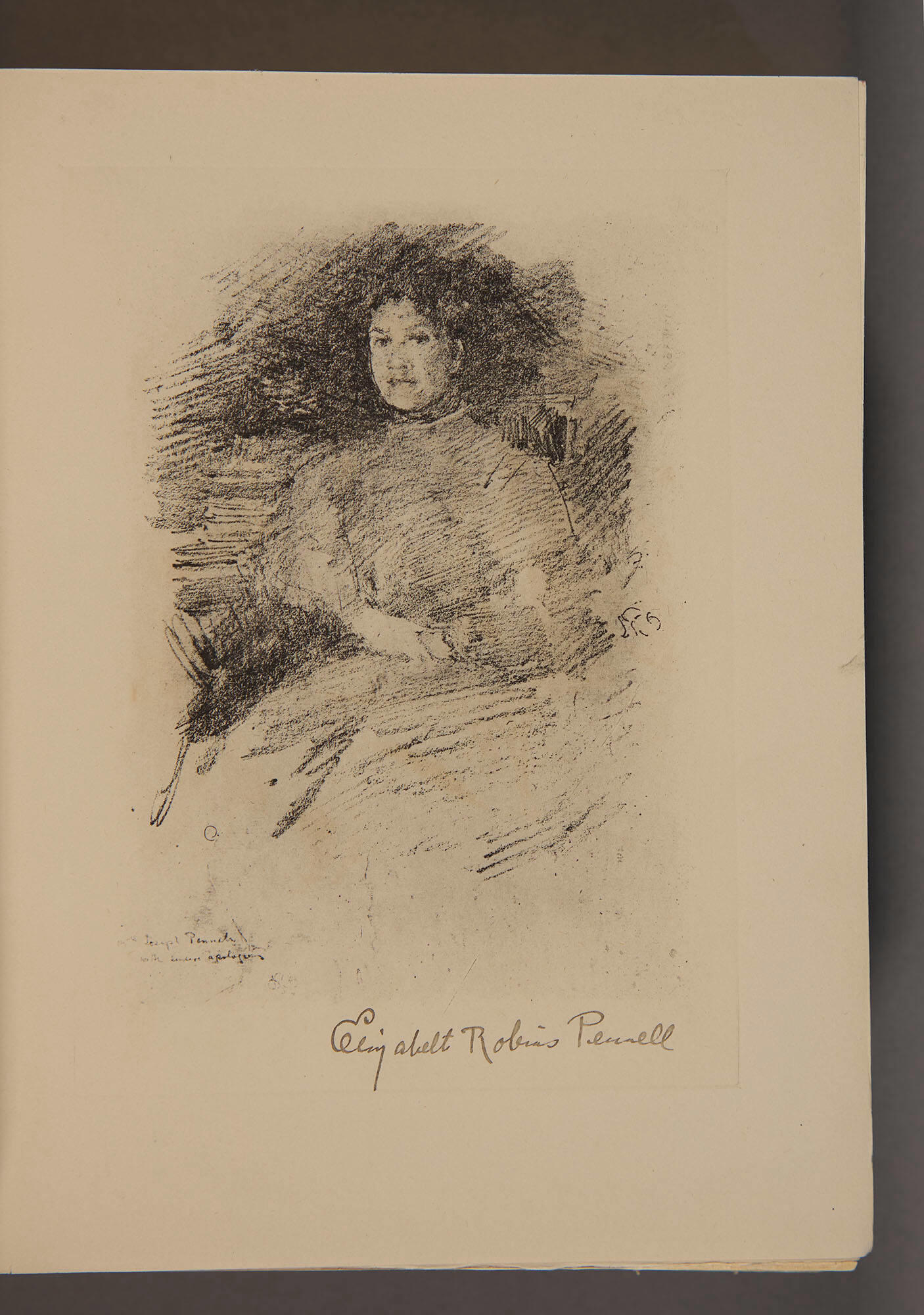

This writer demonstrates a real sensitivity to Madame Manet’s age and class as well as an appreciation of the artist’s inclusion of facial hair and Eugénie’s old-fashioned hairstyle. For this writer, it is the vitality and character of Manet’s sitter that stand out most; Madame Manet is a real woman, not a confection. The author of this vivid account of Madame Auguste Manet at the “Fair Women” exhibition turns out to be Elizabeth R. Pennell (1855–1936), an American writer based in London. She was a travel and food writer, an art critic and scholar of James Abbott McNeill Whistler, and a biographer of Mary Wollstonecraft. The social circle she entertained along with her husband, artist Joseph Pennell, included Aubrey Beardsley, Whistler, Henry James, Oscar Wilde, and George Bernard Shaw—many of whom were Gardner’s friends.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (S.G.S.3.10). Isabella Stewart Gardner displayed this book in the Short Gallery.

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903, artist) and J.B. Lippincott Company (active Philadelphia, 1836–1978, publisher), Portrait of Elizabeth R. Pennell in The Whistler Journal, 1921. Lithograph, 21 x 16.5 x 5.5 cm (8 1/4 x 6 1/2 x 2 3/16 in.)

The review Berenson clipped was signed “N.N.,” no name, and there is no reason to think that Berenson or Gardner would have known that the author was a woman, much less one whose social world was progressive when it came to thinking about gender. Nevertheless, it is worth underlining a couple of points. On one level, Pennell’s piece very much aligns with the other critics who emphasized Manet’s candor about representing an older woman. However, used language that spoke directly to the major concern on Berenson’s mind. As he wrote to Gardner from London on March 30, 1909:

I have the hope of getting you something that I have been looking for for years, something that will connect the Degas with the Pollaiuolo, something that is perhaps more overwhelming, more colossal than either.

Pennell’s observation that in her view, nearby portraits “fade into phantoms” next to the Manet seemed to be just what Berenson was looking for on Gardner’s behalf.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Thomas E. Marr & Son (active Boston, 1910–1942), Long Gallery, 1910. Gelatin silver print

When Madame Auguste Manet first went on view in Fenway Court, Gardner placed the painting on an easel in the Long Gallery on the third floor. The museum-going public took notice, as the Boston Journal reported:

Two hundred persons, the full number of ticket holders admitted in any one day, were at the museum of Mrs. John L. Gardner’s palace in the Fens yesterday . . . Manet’s portrait of his mother, the most recent addition to Mrs. Gardner’s collection of masterpieces, drew particular attention. Mrs. Gardner obtained possession of the painting in Paris only a short time ago, after her agents had been seeking it for years. Specimens of his work are rare in this country.

Angled away from the wall, illuminated mostly by natural light pouring in from the museum’s central courtyard, the painting faced visitors as they walked the length of the gallery. With the easel raising the life-size figure above the level of the chairs, Eugénie met viewers at what was arguably the optimal height for a Manet figure painting—at eye level.

The Courtauld, London (Samuel Courtauld Trust © The Courtauld

Édouard Manet (1832–1883), A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1882. Oil on canvas, 96 x 130 cm (37 ⅞ x 51 in.)

While Isabella moved Madame Auguste Manet to the Blue Room, she is no less imposing as she stares down at the visitor. Like many of Manet’s other famous women–Olympia or the barmaid in Bar at the Folies-Bergère–her gaze is unflappable, a trait that a forceful woman like Isabella Stewart Gardner certainly appreciated.

You May Also Like

Visit the Exhibition

Manet: A Model Family

Gift at the Gardner: Buy the Book

Manet: A Model Family

Read More on the Blog

Gustave Courbet’s Landscape Cleaned up