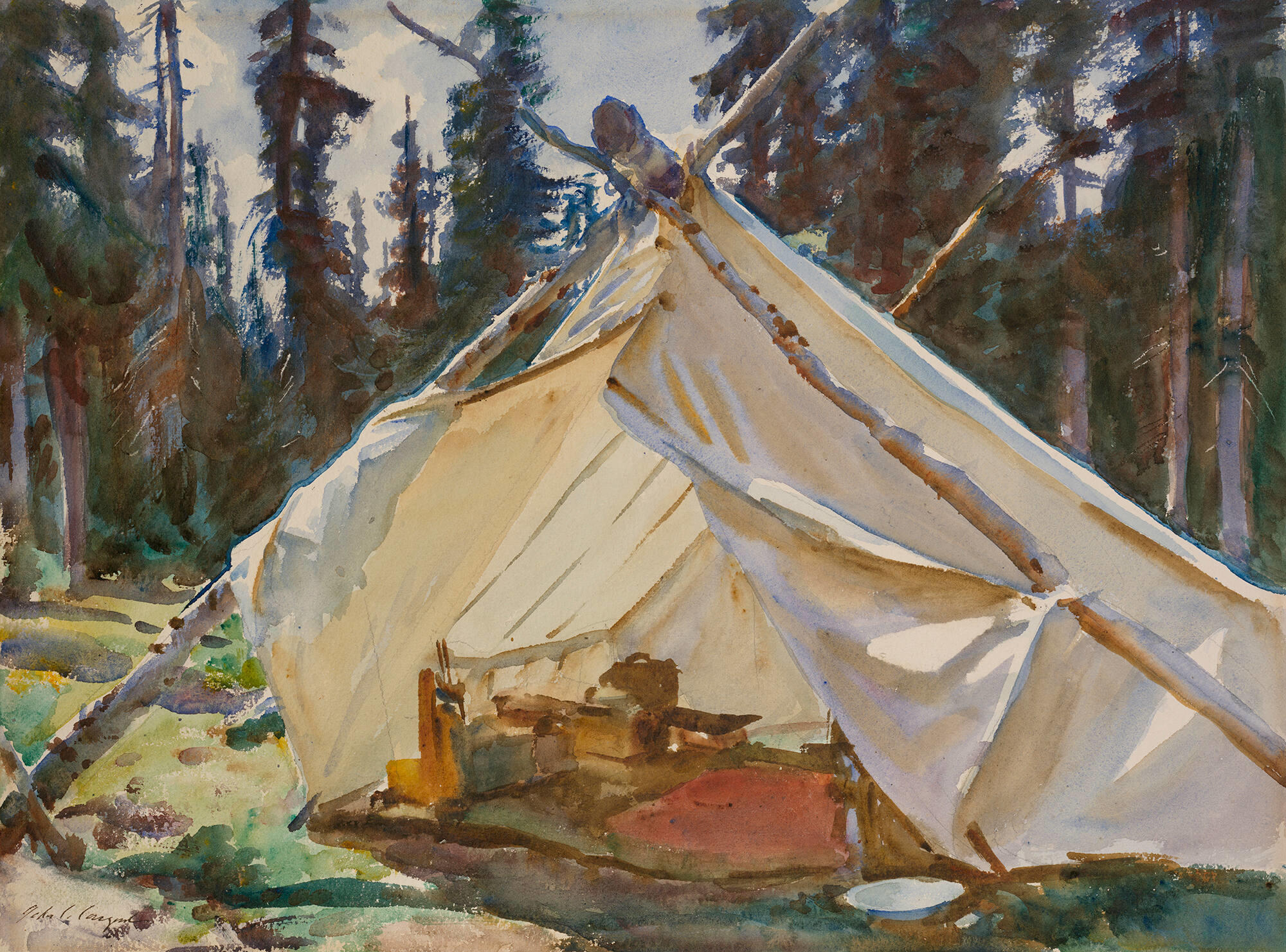

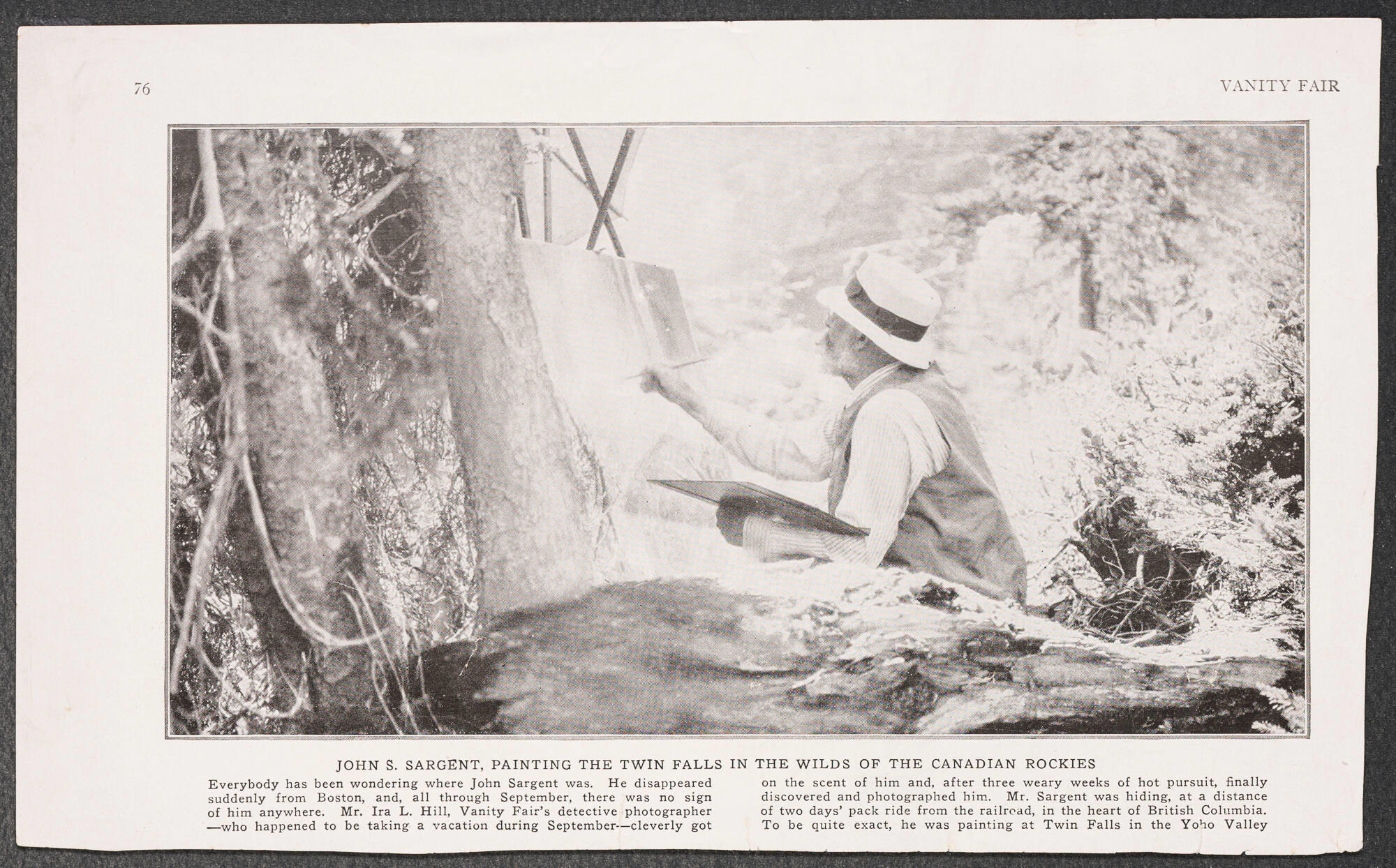

In the spring of 1916, painter John Singer Sargent, a close friend of Isabella Stewart Gardner, returned to the United States from his home in London to continue his work on the monumental decorative program at the Boston Public Library. A few months later, in the summer, he ventured west to Glacier National Park in Montana (established in 1886), and later to the newly formed parks in the Canadian Rocky Mountains, most notably Banff National Park (1885) and Yoho National Park (1886). His journals indicate that he was personally motivated by some rest and the chance to sketch in fresh mountain air. He also wanted to locate and paint Twin Falls which he had seen in a postcard sent to him by Harvard professor and artist Denman Ross, another member of Isabella’s circle. While meant as a break from urban life in Boston, professionally he kept a hectic schedule over the few months that he was away. During this time, he completed a series of watercolors and several oil paintings. Two of this group were acquired by Isabella: Yoho Falls and A Tent in the Rockies.

Sargent found what he was searching for and it was the remote locations of Twin Falls, Emerald Lake, Lake O’Hara, and Takakkaw Falls that he chose to feature in his paintings. Interestingly, he does not paint, write about or even mention the presence of Indigenous Peoples in the region. The more popular Ho-run-num-nay (meaning Lake of Little Fishes in the Indigenous language of local Nakoda Peoples, later renamed Lake Louise in 1882) or Mînî hrpa (Cascade Mountain waterfalls near Banff townsite) were not painted by Sargent. However, waterfalls are sacred for Nakoda Peoples and Mînî hrpa was a key gathering place for meetings, for healing, a place of worship, and for spiritual cleansing.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.006449). Isabella displayed this article in the Sargent / Whistler Case in the Long Gallery.

Vanity Fair (active New York, 1914–1936, publisher), "John S. Sargent, Painting the Twin Falls," November 1916. Ink on paper

As a historian of the Canadian Rocky Mountains, I wonder about the places Sargent visited and the peoples and landscapes he encountered during his journey. At this time, the Canadian Rocky Mountains were far from the idyllic mountain wilderness that Sargent writes about and portrays in his paintings. By 1916, Banff townsite was a significant global tourism attraction with bustling outdoor recreation, cultural and Indigenous tourism economies. The Banff townsite began as a spa destination for elite guests of considerable financial standing. The luxurious facilities built by the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), like the Banff Springs Hotel, completed in 1888, were designed to meet the needs of its affluent clientele and were some of the continent’s most opulent accommodation options at the time. So, Sargent, or any member of the elite social circles that he mixed with in Boston, would not have felt out of place in Banff during this period.

Courtesy of Glenbow Library and Archives Collection, Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary (CU185254)

Boorne and May (active Calgary, 1886–1893, photographers), Canadian Pacific Railway Hotel, Banff, Alberta (later to become the Banff Springs Hotel), about 1888

Romantic Notions of Banff National Park and the Canadian Rocky Mountains

The Banff Hot Springs Reserve (precursor to Banff National Park or Mînî Rhpa Mâkoche in Nakoda) emerged as an elite tourist destination so that the Federal Government and private interests, represented by the CPR, could recover some of the mounting costs of building the national railway to connect Ottawa to the Pacific Coast. Although even today, Banff continues to be greatly romanticized by the Canadian public, there were few conservation objectives that motivated the establishment of Canada’s first and most iconic protected area. Banff is a place that is celebrated globally and it forms a significant part of the Canadian imaginary. International promotional materials for Banff National Park have shaped tourists’ perceptions of the nation for generations.

Vintage Travel and Advertising Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Percy Trompf (Australian, 1902–1964), Banff Canadian Pacific Railway Poster, published in 1938 in Canada

The marketing of Banff also reflected the objective to attract the urban elite of North America and Europe. In fact, beginning in the 1920s, the CPR hired members of Canada’s famous Group of Seven artists to paint the Rocky Mountains and promote the region for tourism. As Lynda Jessup argues, the CPR endeavored to “establish the value of the region, not in the eyes of the traveler as such, but in the eyes of the urban elite that, like the artist it patronized, possessed the cultural capital necessary for discriminating between different landscapes.”

The Thomson Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Photo © AGO

James Edward Hervey MacDonald (Canadian, 1873–1932), Lake O'Hara, Rockies, 1926. Oil on wood-pulp board, 21.5 x 26.6 cm (8 7/16 x 10 1/2 in.)

Access to the Banff townsite and the National Park was rapidly increasing with the 1914 creation of the Calgary–Banff coach road and the proliferation of the automobile. The Park as a playground for people other than society’s elite began with the rise of the automobile and the subsequent expansion of road and highway infrastructure that provided greater access to the region. By Sargent’s death in 1925, this process was well underway.

Courtesy of Glenbow Library and Archives Collection, Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary (CU1110468)

Unidentified photographer, Automobiles en route to Banff, Alberta, 1917

The Ancestral Lands of Diverse Indigenous Peoples

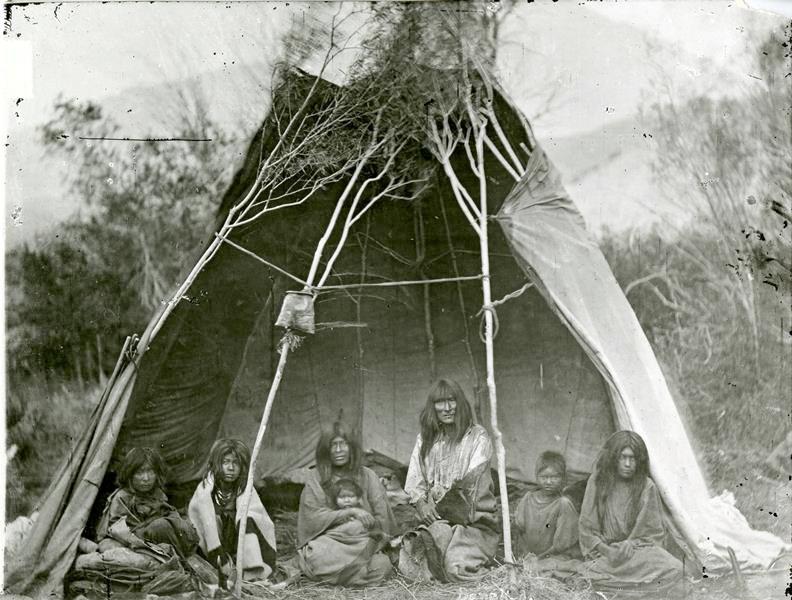

Prior to these developments in Banff, and also in contradiction to the empty mountain landscape Sargent painted, the Banff–Bow Valley was a key gathering place for diverse groups of Indigenous Peoples. For centuries, the Nakoda, and other groups of Indigenous communities, lived throughout the Banff–Bow Valley in what would become the western Canadian province of Alberta. For example, the Banff-Bow Valley and the Bow River, called Mînî Thnî Wapta (Cold Water River), have been the traditional spiritual center of the Nakoda Peoples since time immemorial. As the giver of life, the valley provides traditional foods, medicinal plants, shelter, animals to hunt, as well as sacred areas and vision quest sites for Nakoda Peoples.

Courtesy of Glenbow Library and Archives Collection, Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary (CU195763)

Unidentified photographer, Bow River Valley, Alberta, 1930s

The river forms the center of Nakoda culture, economies, family and ways of living off the land. Beginning with the arrival of Europeans to the valley in the late eighteenth century, Indigenous Peoples were forced to undergo a series of significant changes that would alter aspects of a well-established way of life that had persisted for millennia. Today, Yoho National Park recognizes the ancestral lands of the Ktunaxa and Secwépemc First Nations and Banff National Park acknowledges the Bearspaw, Chiniki and Goodstoney (Nakoda) First Nations, the Siksika, Kainai and Piikani (Blackfoot) First Nations, the Tsuut’ina First Nation and the Métis Nation of Alberta [Indigenous Connections at Banff National Park and Yoho National Park].

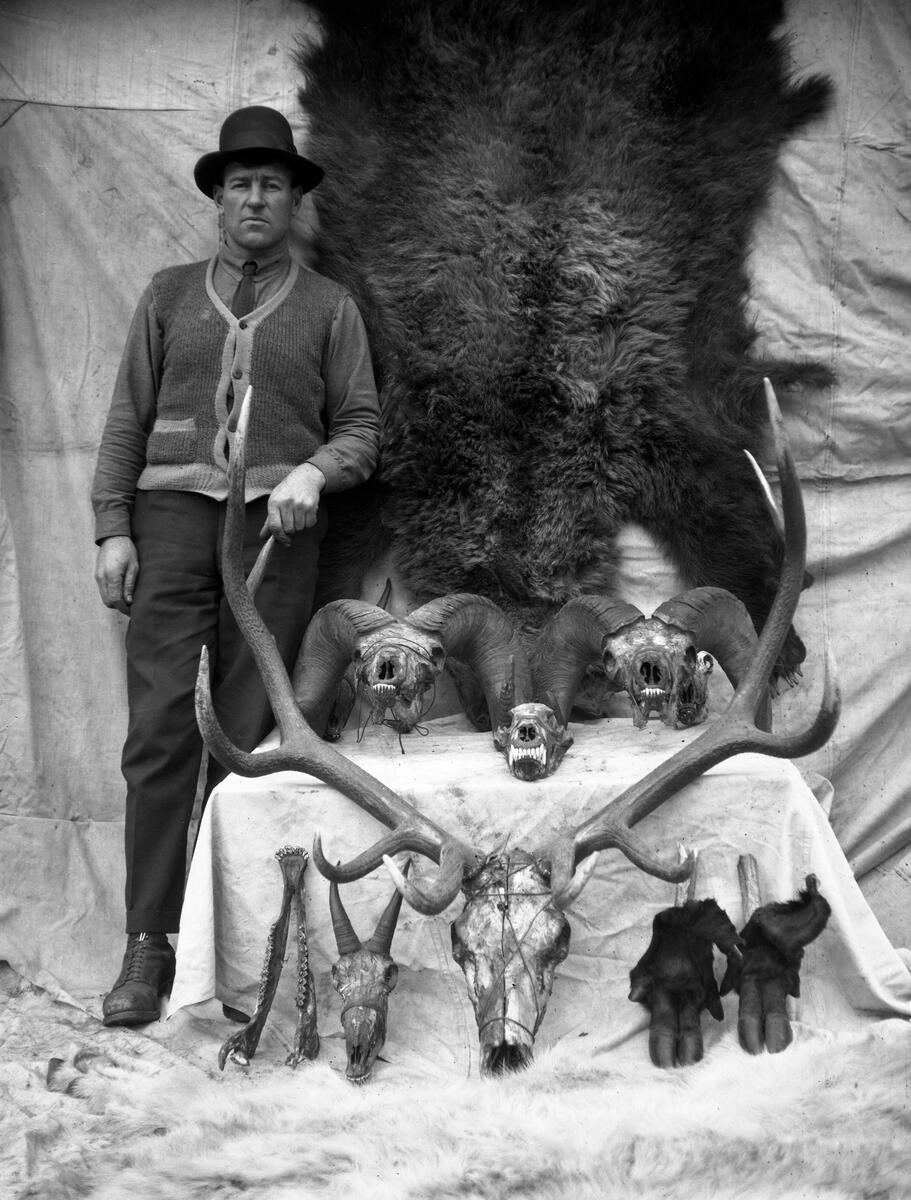

Sport Hunting and Fishing Economies

The Canadian Rocky Mountain National Parks are places that are supposedly protected for the enjoyment of “all” Canadians, but they also have a history as recreation paradises. Skiers, hikers, mountaineers, and paddlers have been attracted to the Canadian Rocky Mountains for well over a century. Sport hunting and fishing were also important recreational activities that brought thousands of tourists to the region throughout the first few decades of the 20th century. In 1912, the CPR actively began to promote the exceptional hunting and fishing opportunities in the park to international audiences. These opportunities became one of the region’s largest draws for early tourists. In his memoirs, John Murray Gibbon, the celebrity hunter and famous promoter of the Banff region, mentions meeting Sargent—even specifically seeking him out when he heard the artist was in the area. Sargent may have even had the opportunity to go on a guided hunt in pursuit of big game during his time in Banff or Yoho.

The Presences and Absences of Indigenous Peoples

In 1872, the Yellowstone Park Act incorporated lands where several Indigenous groups had been exercising their off-reservation treaty rights to hunt, fish, and gather. This led to the removal of Indigenous Peoples from Yellowstone National Park and set a precedent for the creation of further conservation spaces in the United States with the same founding principles. In this respect, Yellowstone not only was the first example of the removal of communities to preserve “nature,” but it also provided a model for the displacement of Indigenous Peoples from national parks throughout the continent in the decades to come.

This photo was taken as part of the U.S. Geological Survey. Courtesy of National Park Service,

William Henry Jackson (American, 1843–1942, photographer), Tukudika (Sheepeater) men, women, and children at Medicine Lodge Creek, Idaho, in 1871. The Tukudika, or Sheep Eaters, are a band of Mountain Shoshone that lived for thousands of years in the area of Yellowstone National Park. Twenty-seven tribes have ties to the area and resources now found within Yellowstone.

The formation of Canada’s first national park had significant consequences for local Indigenous communities too. Through the creation of Banff National Park, new ideas around the conservation of wildlife emerged that were central to the new parks’ system and the restrictions placed on Indigenous communities that repressed their cultures. As the park was redefined as a protected space, new regulations targeted Indigenous hunting practices. Competing ideas of conservation and what constituted “wilderness” informed further government policies designed to assimilate the cultures of Indigenous Peoples. Due to the perceived threat of their hunting to local wildlife, Indigenous communities were displaced from their ancestral territories when the park was formed and for decades, they were continually denied access to the region. Paradoxically, during this period when Indigenous Peoples encountered serious constraints to hunt, fish and gather, sport hunting by Euro-Canadians and tourists alike was actively encouraged inside park boundaries because of the popularity of these recreational activities and their importance to burgeoning tourism economies.

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Louise E. Bettens Fund (1916.496)

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925), Lake O’Hara, 1916. Oil on canvas, 97.5 x 116.2 cm (38 3/8 x 45 3/4 in.)

When we appreciate the exquisite paintings that Sargent produced during his visit to the Rocky Mountains, surrounded by the towering peaks of Lake O’Hara, it is difficult to imagine that these landscapes are also filled with complex histories of displacement and cultural loss. We would all do better to approach these special places, and the art that they inspired, with humility and a recognition of the past and contemporary presences of the communities that have called them home for millennia.

References and Further Reading

Jessup, Lynda. 2002. “The Group of Seven and the Tourist Landscape in Western Canada, or The More Things Change …” Journal of Canadian Studies 37, 1: 144–79. https://www.utpjournals.press/doi/10.3138/jcs.37.1.144

Mason, Courtney W. 2014. Spirits of the Rockies: Reasserting an Indigenous Presence in Banff National Park. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. https://utorontopress.com/9781442626683/spirits-of-the-rockies/?srsltid=AfmBOoo-QXs4y1seMzmAiRtaDtNTlUU7pQ4LQ_wGLc2yaYxdNrCTofDm

Snow, John. 2005. These Mountains Are Our Sacred Places: The Story of the Stoney Indians. Toronto: Fifth House Publishing. https://goodminds.com/products/1894856791

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

Searching for Answers: Isabella’s Native American Basket

Watch a Video on You Tube

Amplifier Project: Indigenous Voices

Recognizing Indigenous Peoples' Day

Connection to Place, 2024