A visitor to the Museum may miss the Black Glass Madonna in the Veronese Room, displayed inside a highly ornate eighteenth century Italian vitrine. It would, however, be a pity to overlook this truly special and quite unusual object—that, until very recently, had an unknown history.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Sean Dungan

The Black Glass Madonna inside a vitrine in the Veronese Room

Black Madonnas

In a love poem from the Old Testament book Song of Solomon of the Hebrew Bible, a woman sings to her lover, and compares her beauty to two objects that are treasured in her culture for their rich, dark color.

I am black, and beautiful, O ye daughters of Jerusalem, as the tents of Kedar, as the curtains of Solomon.

During the Middle Ages, the poem was reinterpreted for the Virgin Mary, specifically Black Madonnas. In 1960s America, the message was adopted by the “Black Is Beautiful” movement, as a message of empowerment for Black women; one that continues today.

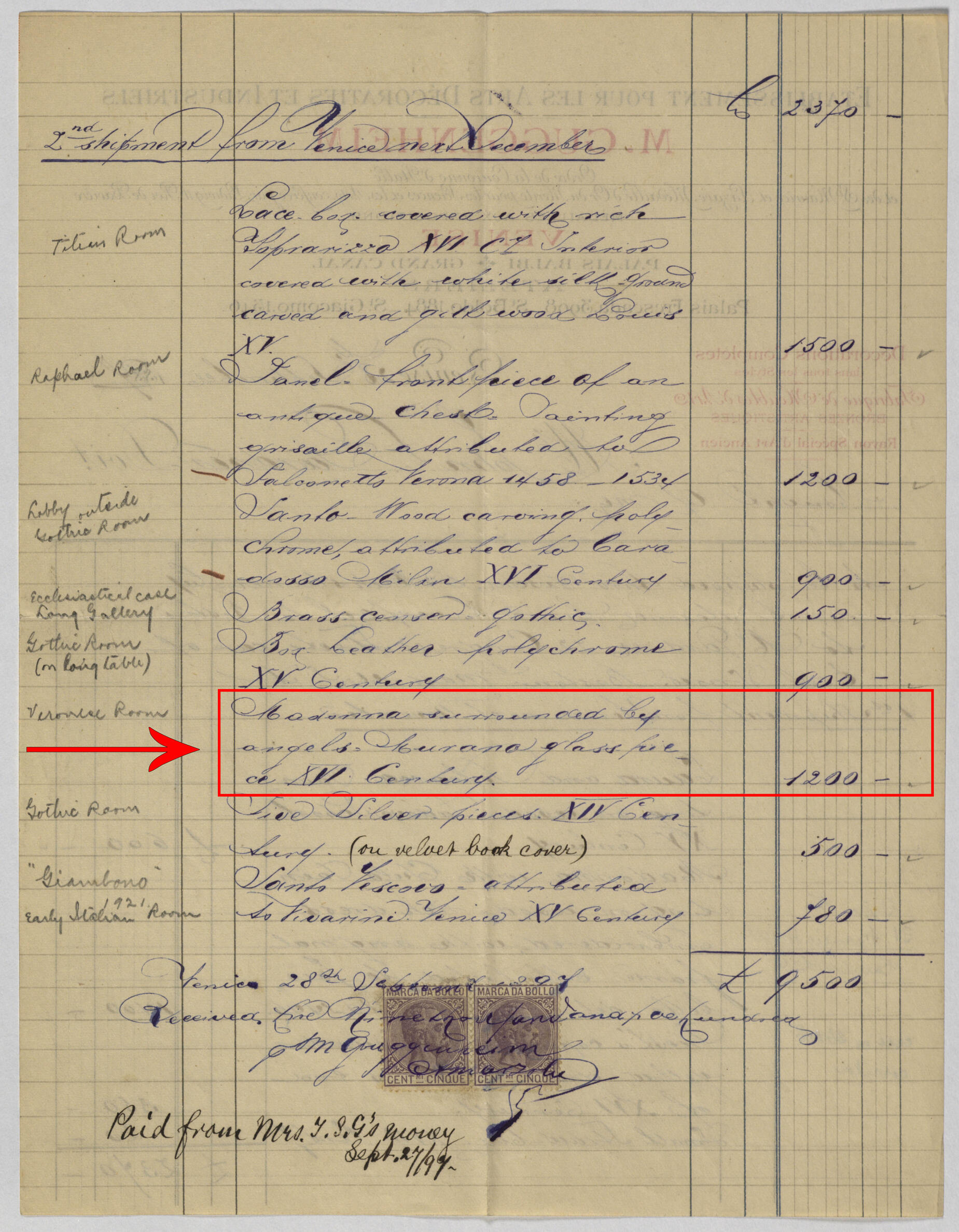

Isabella Stewart Gardner purchased the Black Glass Madonna from a dealer named Michelangelo Guggenheim (1837–1914) in Venice on September 27, 1897. It was described on the receipt as a Venetian Murano glass Madonna surrounded by angels from the 1500s. While this information is mostly correct, it was incomplete. Come along with us on the journey to figure out what kind of Madonna this is, where it came from, and why it was—exceptionally for the period—made of glass.

Which Black Madonna?

The first step to learning more about the Madonna was to look closely at its iconography. It shows the Virgin and Child surrounded by other figures, likely saints because they have halos, and God the Father at the pinnacle, who is also made in black glass, possibly to make a visual connection between the Holy Family.

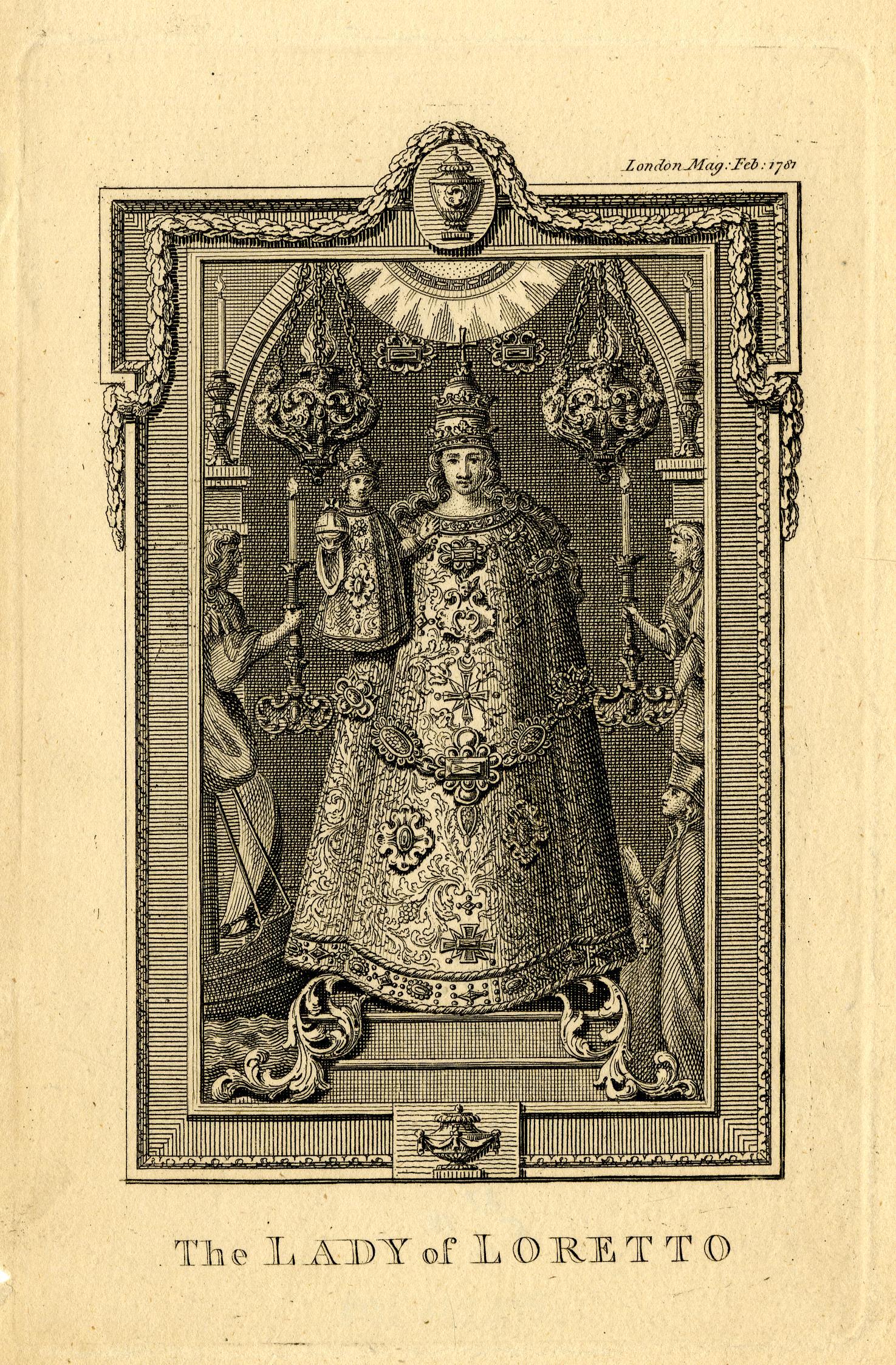

There are several well-known Black Madonnas, such as Our Lady of Częstochowa in Poland, but the Gardner’s piece has a papal tiara, linking it to Our Lady of Loreto in Italy.

The Museum’s Black Glass Madonna is likely based specifically on the statue of Our Lady of Loreto from the Basilica della Santa Casa in Loreto, Italy of a Black Madonna and Child. In the legend of Our Lady of Loreto, there was a flying house carried by angels that landed on the property of a woman named Laureta, hence Loreto, in the Italian town of Recanati on 2 December 1295. When townspeople looked inside they saw a dark painting of the Virgin. In a vision to a hermit who most frequently visited her, she told of her journey from Nazareth to several other towns before landing in theirs and deeming it worthy as her seat.

Murano Glass

Even though we identified the source of the imagery, there was still an important lingering question: why is this Black Madonna made of glass? This was atypical for Black marian imagery, and at first it stumped experts both in historical glass and the history of Black Madonnas.

Looking closely at the object, it is clear from the techniques used that it is Murano glass. Made in a small lagoon island near Venice, the quality of the glass and complex designs of glass pieces were highly prized by those who could afford it. Glassmakers employed a technique called lampworking in which they used a blowtorch type tool called a “lamp” that could direct the flame on glass pieces to melt and then manipulate the glass. This is one of the techniques we see used on the Museum’s Black Glass Madonna and many other decorative glass objects from the workshop it may have originated from.

Photo: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Trina Urrata-Weintraub of Fiamma Glass Studio in Waltham, Massachusetts, demonstrates lampworking, a technique Venetian artists used to create the Black Glass Madonna

The technology and skill of glassmaking in Murano was a closely kept secret; one that the Venetian government protected at great lengths. The movements of the glassworkers were highly controlled, and if a glassworker from the island left without prior permission, the penalty could be as harsh as death. Inevitably, Murano-style glass making made its way into the rest of Europe and is referred to as façon de Venise, meaning in the style of Venice.

Archduke Ferdinand II and his Glasshouse

Among the many fans of Murano glass was Archduke Ferdinand II of Austria. Born 14 June 1529 in Linz, he was the second son of Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I (1503–1564) and Anna Jagiellon of Bohemia and Hungary (1503–1547) making him a part of the House of Habsburg. He became sovereign of his own lands in 1567 of Tyrol and Further Austria. The Archduke’s Ambras Castle in Innsbruck was a center of culture. Ferdinand was described as a true Renaissance prince because of his love of art, music, and dance. His obsession for beautiful things was well-known. A voracious collector, he amassed thousands of objects including artworks, things from the natural world, and curiosities. He kept his collection in a specially constructed building at his castle that still stands today at the Ambras Castle Innsbruck museum—considered the oldest museum in the world. Isabella traveled to Innsbruck and visited Schloss Ambras in 1886.

When Ferdinand established a glasshouse—namely a glass-making workshop—at his court in 1570 he received permission from the Venetian government for glassworkers to come from Murano to work in Innsbruck. (In fact, less nicely, the workers were described as being “on loan” to Ferdinand’s workshop.) Initially, the agreement with Venice stipulated that anything made at the glasshouse could not be sold to the public, although toward the end of the glasshouse’s activity contracts with the glassworkers were renegotiated to allow them to make objects to sell as long as it was done on their own time. Letters about this arrangement between the Archduke and his imperial envoy in Venice Veit von Dornberg (about 1529–1591) survive in the archives of Ambras Castle.

He wrote in a letter dated 23 July 1570 that he sought the “most capable, honorable and familiar [with glassworking], and who has the least fantasy in him,” meaning he wanted someone with the skill to make the glass objects that stemmed directly from his own imagination. Ferdinand’s imagination was vast and, fortunately for us, many of the glass objects survive today, and can be found largely at the Schloss Ambras Innsbruck and the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna. Many of the diorama-like glass objects, sometimes referred to as glass boxes, depict scenes from the Bible and other religious themes, and the Black Glass Madonna may represent the Archduke’s faith and commitment to Catholicism.

It is this commitment to Catholicism that provided the final key that the Black Glass Madonna is from the Innsbruck glass house. During Ferdinand's lifetime, Protestantism was on the rise and the religious movement known as the Reformation challenged the papacy and the authority of the Catholic Church. After a pilgrimage to Loreto, the Archduke vowed to be a protector of the Catholic faith. Among his activities in promoting the faith was funding chapels dedicated to Our Lady of Loreto throughout his lands. It would, therefore, make sense that his own glass house would produce an Our Lady of Loreto.

Now that we have uncovered some of the mysteries of this exceptional object, we hope to learn even more about her. The Museum’s Conservation department conducted XRF analysis in 2023 and confirmed that the chemical element manganese was used in the Museum’s Black Madonna to create the dark colored glass for the Virgin, Christ Child, and God the Father figures. But that’s just the beginning! Stay tuned for a future blog post to find out how our conservators used additional scientific analysis to learn even more about the glass composition as well as explain how they conserved this fragile object so that it could sparkle once again.

Photo: Jessica Chloros

Detail photo of the Black Glass Madonna in the Conservation Lab with darts indicating areas for XRF analysis.

The Black Glass Madonna is featured in the special exhibition Visions of Black Madonnas October 23, 2025 to January 19, 2026 in the Fenway Gallery. After that, you can see it in the Veronese Room!

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

Botticelli’s Virgin and Child: Infrared and Ultraviolet Light Imaging

Read More on the Blog

Madonnas on Parade: Fra Angelico and the Fisherman’s Feast

Gift at the Gardner

Venetian Glass: The Olnick Spanu Collection