Cafe G is closed for repairs from January 29 through February 16, 2026.

We apologize for the inconvenience.

In the fall of 1993, the artist Allan Rohan Crite (1910–2007) spoke at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. His talk was part of a lecture series for which many notable artists and scholars gave talks at the museum—including Professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Faith Ringgold, Maurice Sendak, and Betye Saar.

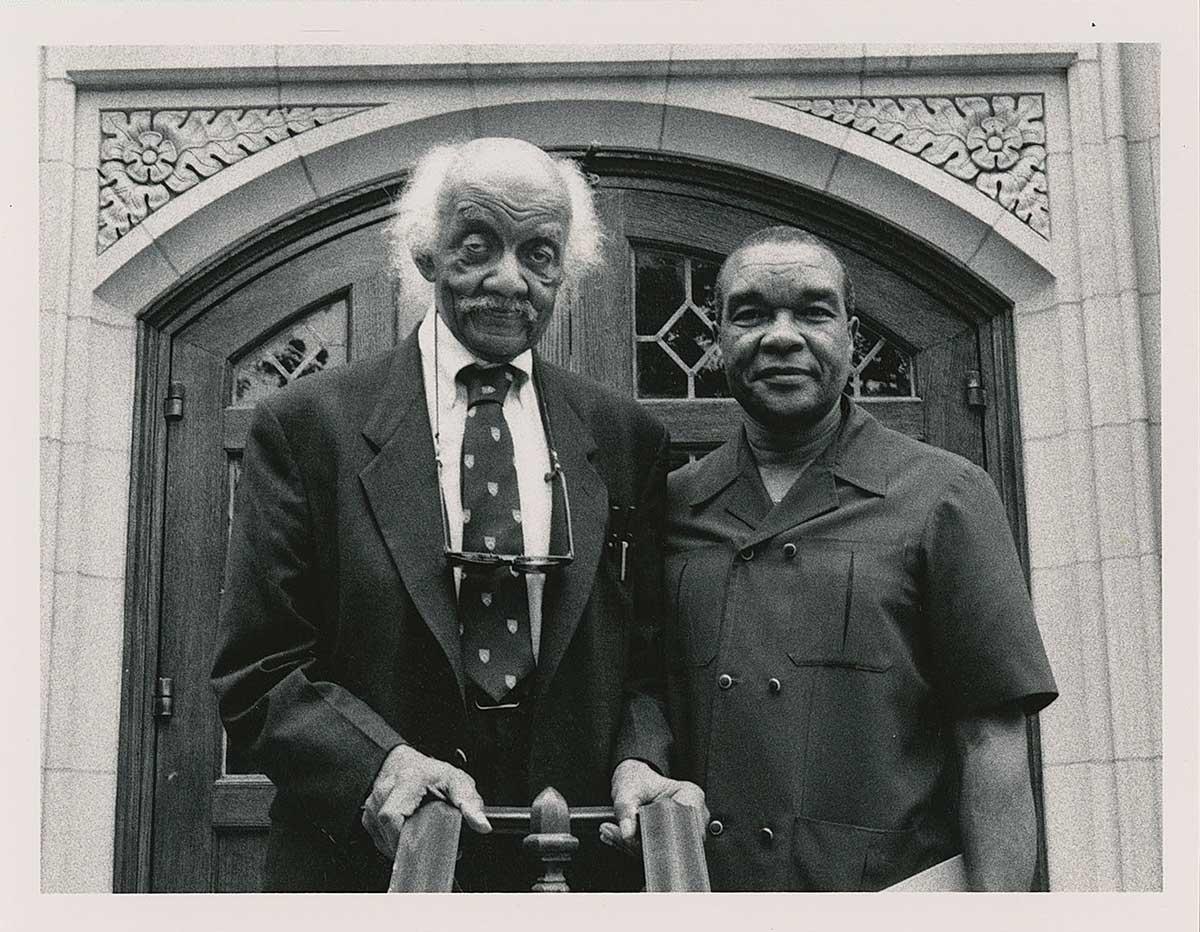

Allan Rohan Crite and David C. Driskell in front of the National Cathedral in Washington, DC for an event honoring Crite, 1990s

Courtesy of the David C. Driskell Papers at the David C. Driskell Center at the University of Maryland, College Park. Gift of Prof. and Mrs. David C. Driskell (MS01.11.01.P0565)

In his talk, Crite described the growing interaction of global cultures from the Renaissance to the nineteenth century—from Europe to East Asia to the Americas, including a discussion of slavery in the Americas and his own ancestors’ enslavement in Peru. Ultimately, he argued the Gardner Museum both reflected this globalized historical world and pointed to the future. “You look at the things of the Renaissance that are represented here [in this] spectacular place and get an understanding of the role of the Renaissance, how it developed into [what] we knew as the 19th century and the world that we know today. By looking at the past, it gives some sense of what we can do in the present and we sort of make some kind of projection into the future.”¹

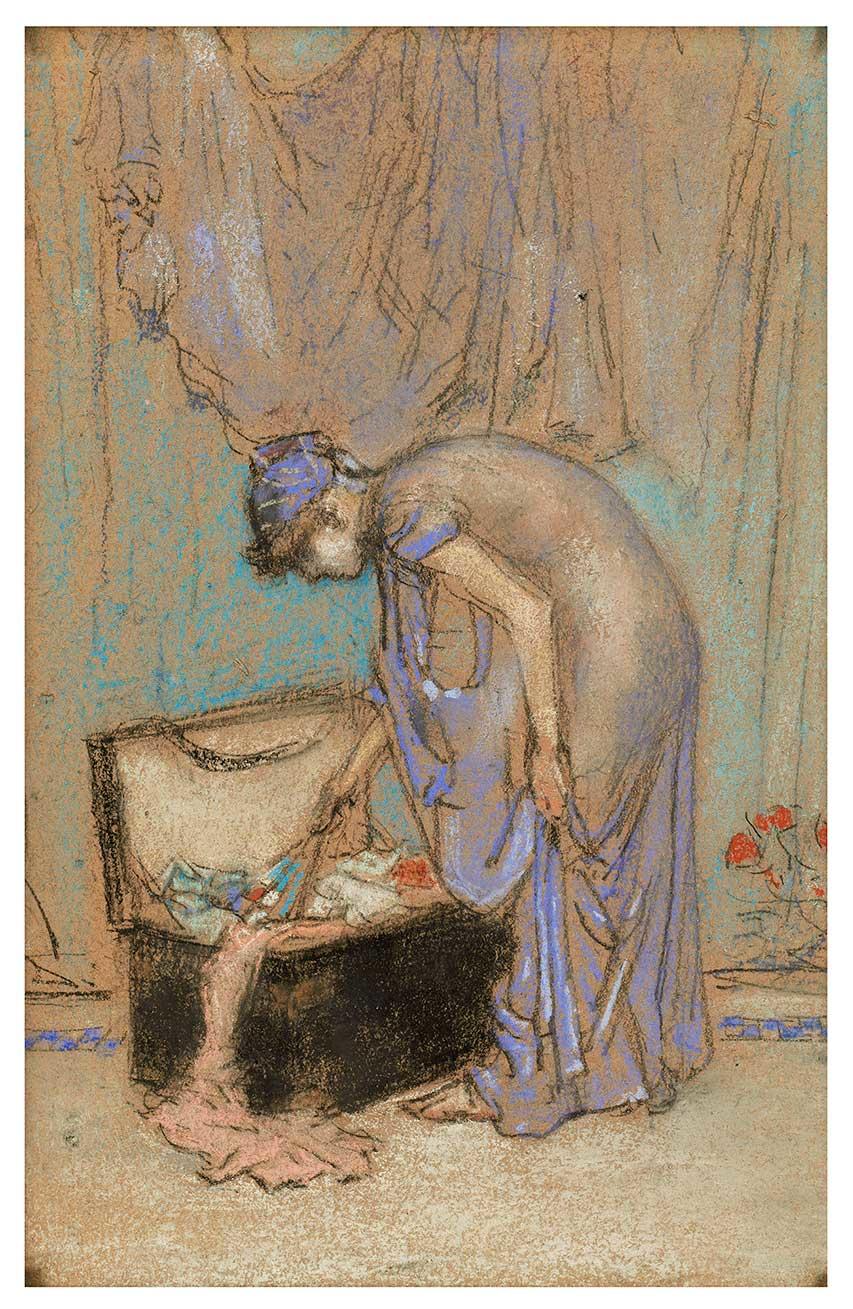

Crite used images from the collection to accompany his lecture. They included works as diverse as the Egyptian Horus Hawk (331-323 BC), Francesco Pesellino’s Triumphs of Love, Chastity and Death (about 1450), and James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s The Violet Note (1885-1886). Despite the global scope of his talk, Crite concluded his lecture with something decidedly closer to home: a personal story about his relationship to the Gardner Museum and its founder, whom his mother met.

The artist grew up in the Boston neighborhood of Lower Roxbury, at 2 Dilworth Street, a twenty-minute walk from the Museum.² As a child, he and his mother—Annamae Palmer Crite—regularly visited museums and other cultural sites around Boston. She described in an oral history interview that her son showed an early artistic talent: “The teachers were amazed at his development in drawing…They told me about the Children’s Art Centre here in the South End and thought he should go there. I said yes.”³ The Children’s Art Centre, established in 1914 at 36 Rutland Street (about a thirty-minute walk from the Museum), sought to provide arts education and enrichment to children, regardless of race, ethnicity, or economic background. The Centre arranged outings to local arts institutions, including the Gardner. Crite vividly described one of these visits to the Gardner at the conclusion to his lecture, as well as a decade prior in an oral history interview for the Archives of American Art:

We used to make trips up to the Isabel Stewart/Jack Gardner palace. I remember going there. Of course, the collection they have there is just a blaze of color, the courtyard. I made several drawings. One of them was sent to Mrs. Gardner and she was rather pleased—...

"...—she was still alive at the time, this was before 1924 (I think she died that year). My mother tells me—she came out with a group of children from the Art Center, and Mrs. Gardner saw her and asked her to come in and sit down and have a cup of tea with her, so she did. That's one of those little pleasant incidents—sitting and having tea with this rather fabulous woman. My mother recalls that she seemed rather sad. I suppose Mrs. Gardner may have had her moments of sadness—I think she lost her only child; she was incapable of children. And the palace was, I suppose, a kind of substitute, in a way. But, at any rate, it was my introduction to the place. And, as I said before, I just remember this blaze of glory, of color, of flowers and the streaming down in the courtyard; and then of course the mysterious nooks and corners, with bits of Italian paintings and carvings...”⁴

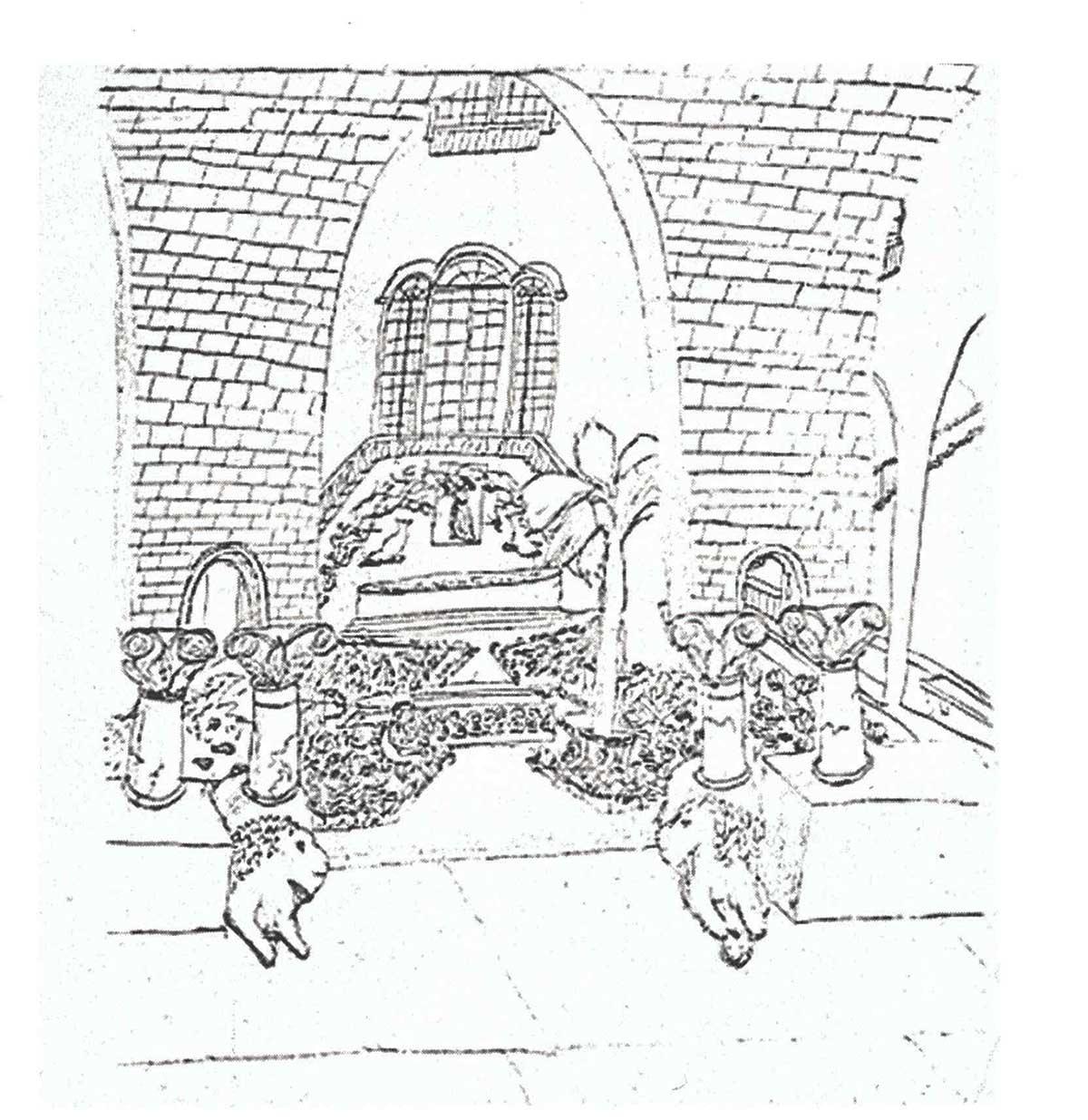

A small reproduction of Crite’s childhood drawing of the courtyard features in the publication commemorating his lecture. The location of the original remains a mystery. However, it resembles other early works by Crite in the collections of the Boston Athenaeum and the Addison Gallery of American Art.

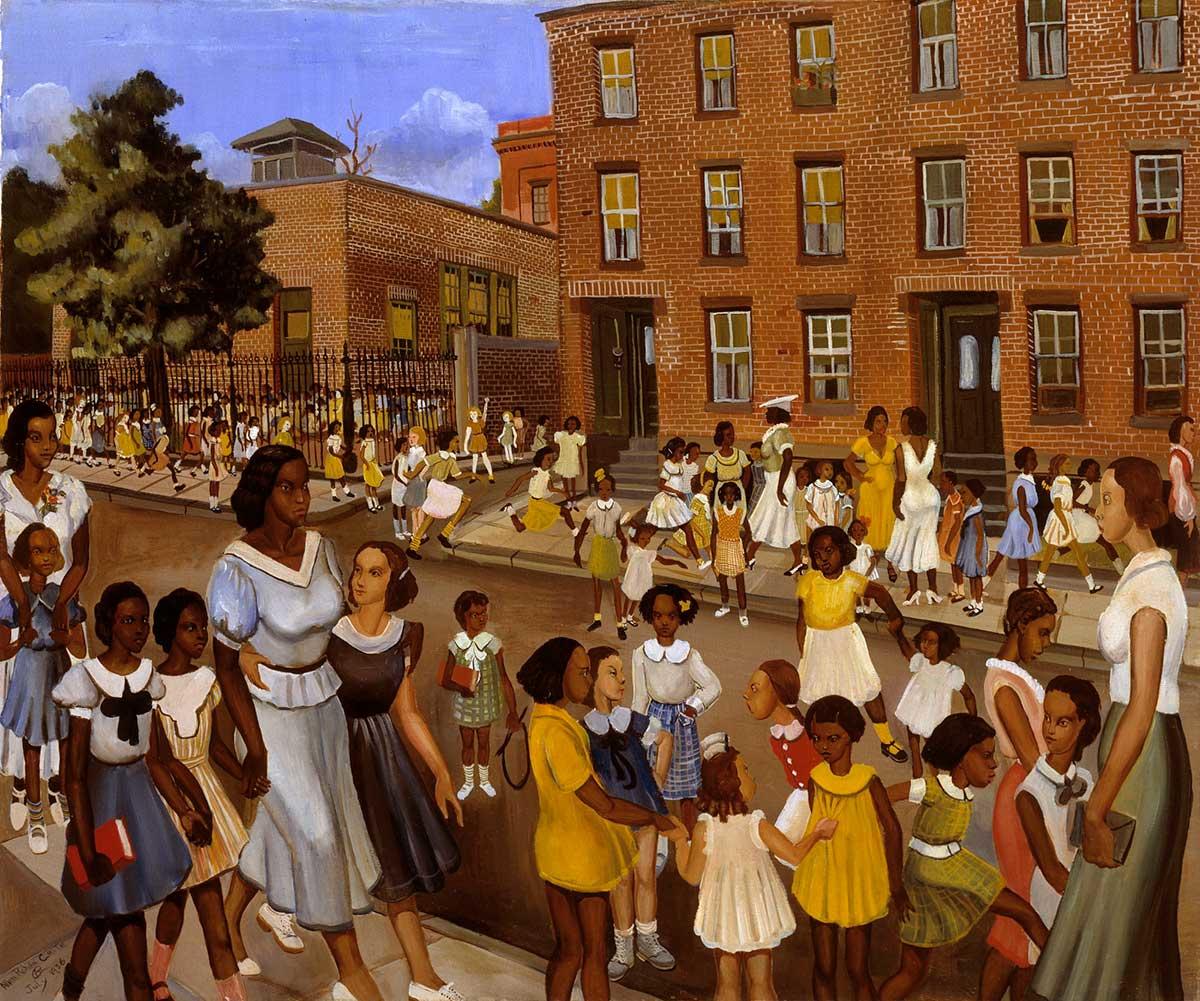

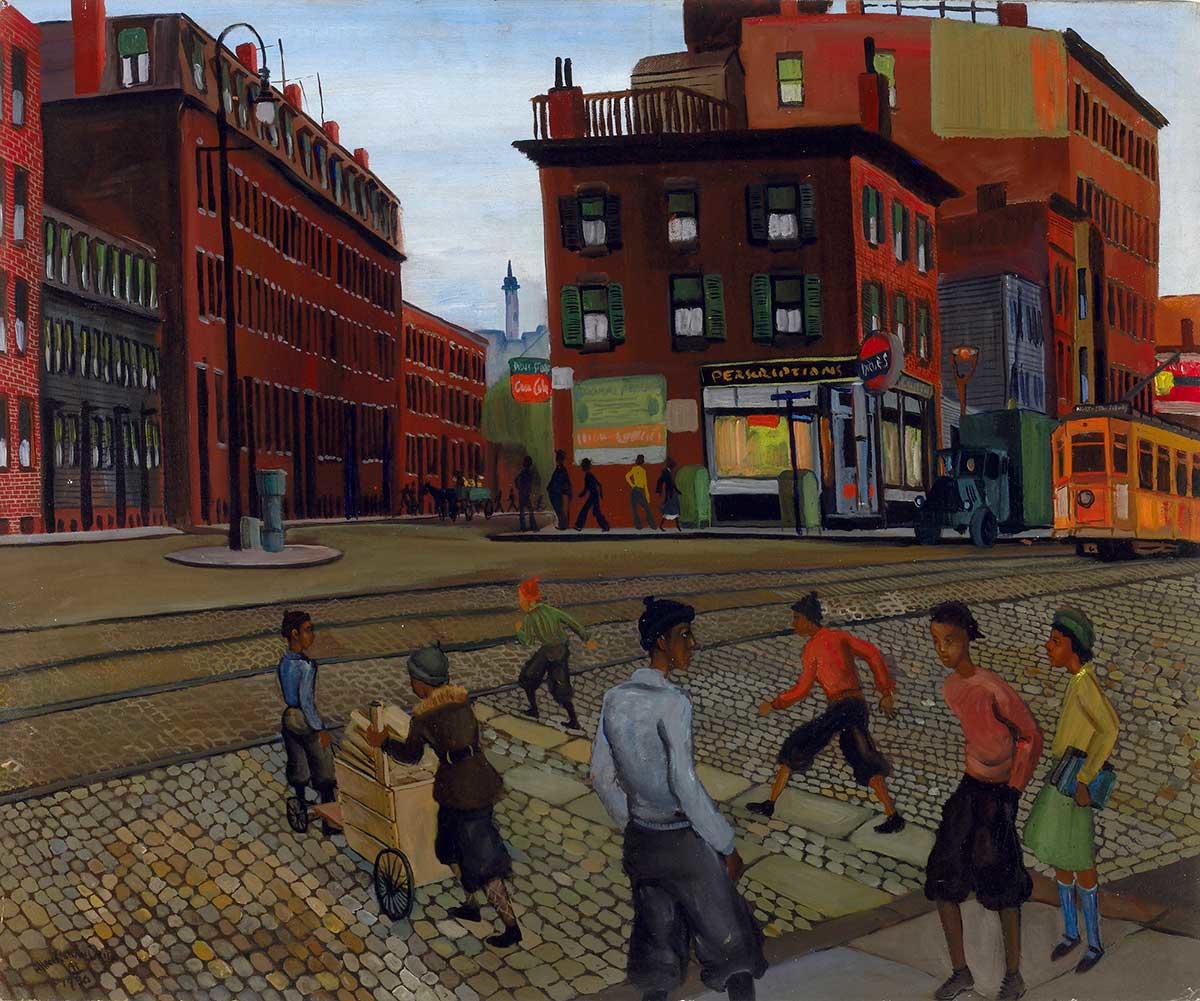

While these works are monochrome crayon drawings, his later paintings demonstrate his fascination with color—a fascination that he had even as a child seeing the Courtyard for the first time. In 1936, Crite graduated from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts and spent the next decade creating vivid depictions of life in Roxbury and the South End. Works in the Smithsonian American Art Museum, St. Louis Art Museum, and many other institutions depict street scenes in these neighborhoods—recording daily comings and goings and elevating these quotidian moments by recording them on canvas.

Both Crite’s long personal connection to the museum and his paintings reveal the histories of the communities that exist beyond the courtyard—notably the vibrant Black communities within walking distance of the Museum. As the artist himself described in his lecture, the Gardner has a global scope. Despite encompassing so much of the world and art’s history, the collection has many blind spots: including a record of the dynamic neighborhood in which the institution itself exists. Just like the timeline of Thomas McKeller’s Boston in the recent exhibition Boston’s Apollo, Crite’s works and recollections remind us of the histories that were unfolding just steps from the Palace but are too often overlooked.

The author would like to acknowledge Jean Gibran for her invaluable assistance in providing information about resources available about Crite’s life and work.

Explore the Exhibition

Boston’s Apollo Gallery Guide

Read More on the Blog

Ned Gourdin: An Exceptional Bostonian

Learn about how the Gardner works with artists today

Working with Artists

¹ Eye of the Beholder Lecture Series Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum: Allan Rohan Crite Wednesday, September 22, 1993, 6:30 p.m, transcription in the Museum Archives

² Julie Levin Caro, “Rooted in the Community: Black Middle Class Identity Performance in the Early Works of Allan Rohan Crite,” Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Texas at Austin, p. 87

³ Edward Clark, Annamae Palmer Crite, and Allan Rohan Crite. "Annamae Palmer Crite and Allan Rohan Crite: Mother and Artist Son: An Interview." MELUS 6, no. 4 (1979): 67-78. Accessed December 16, 2020. doi:10.2307/467058

⁴ Oral history interview with Allan Rohan Crite, 1979 January 16-1980 October 22. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.