General admission for children 17 years and under is always free

Throughout midsummer at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Agapanthus wraps the Courtyard in blue. A treasured plant in the Museum’s living collection, Agapanthus can flourish pot-bound for up to 75 years. Soaring over its arching, straplike leaves are elegant spikes of cobalt-colored flowers. The trumpet-shaped florets in each spherical umbel resemble miniature lilies. This resemblance may begin to explain the origin of its enduring misnomer—lily of the Nile.

Photo: Jenny Pore

The History of Agapanthus

Despite its common name, the lily of the Nile is neither a lily nor native to the Nile River basin. Indigenous to southern Africa, Agapanthus thrives in the understory along the banks of rivers and streams. The taxonomic history of Agapanthus is curious. Once included in the lily family, it was found to be more closely related to daffodils and onions. Agapanthus has now settled into the Amaryllis family within its own subfamily—Agapanthoideae.

Photo: Jenny Pore

Summer Blues display in the Courtyard of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2022

The etymology of the genus Agapanthus comes from the Greek words for love (“agape”) and flower (“anthos”). One of several Greek words for love, agape represents divine love—or love of humanity—in contrast to “eros” (intimate love) or “philia” (brotherly love). Agapanthus has been symbolic of love long before its naming. This connection can be traced back to the guardians of its native land.

In South Africa, Agapanthus has been valued as a magical and medicinal plant since ancient times. Prized as a love charm, the plant was believed to be a powerful aphrodisiac. Xhosa women traditionally wore necklaces made of the roots to encourage fertility and good health during pregnancy. Roots have been boiled for a tonic to induce labor. Many toxic plants have been used medicinally throughout history—Agapanthus is no exception. All parts of the plant are poisonous.

Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Pierre-Joseph Redoute (Belgian, 1759–1840), Illustration of Agapanthus umbellatus from Redoute’s Les Liliacees, vol. 2, Paris, 1805–1816.

Agapanthus has been utilized in traditional medicine for a number of ailments. Zulu people harness the plant to treat heart disease, cough, cold, paralysis, and chest pain as Agapanthus is known to have anti-inflammatory properties. Winding the leaves around wrists and feet is thought to bring fevers down and reduce swelling. Although the plant’s sap can irritate sensitive skin, the long, strappy leaves make an ideal bandage to hold a poultice in place.

Photo: Jenny Pore

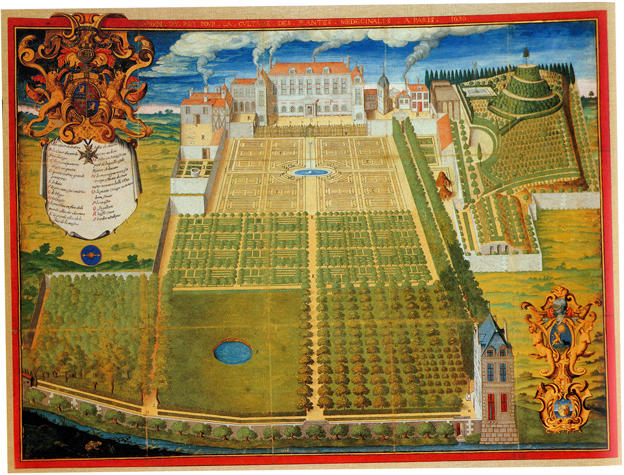

Agapanthus first escaped its native land in the mid-17th century. Specimens harvested near the Cape of Good Hope were brought to Europe by the Dutch East India Company and donated to botanical gardens with greenhouses. One such garden was the Jardin des Plantes of Paris, founded in 1635 by King Louis VIII as the Royal Garden of Medicinal Plants—or Jardin du Roi. Agapanthus umbellatus—now known as A. africanus—was noted as having reached the United States by 1806 in The American Gardener’s Calendar by horticulturist Bernard McMahon of Philadelphia. Today Agapanthus grows in tropical to mild temperate zones across the globe and has become naturalized in habitats as diverse as Australia, Great Britain, Ethiopia, Jamaica, and Mexico.

Bibliothèque du Muséum national d'histoire naturelle, Paris. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Frédéric Scalberge (French, 1542–1640), View of the Jardin du Roi, Paris, 1636. Watercolor on vellum. Published in the frontispiece of the Description du Jardin royal des Plantes medicinales, 1641, by Guy de La Brosse (French, 1586–1641)

Agapanthus in Art

Alongside his cherished waterlilies, Claude Monet cultivated the lily of the Nile in his gardens at Giverny. The water meadow he shaped with care afforded changing illuminations of his subjects. Monet’s impressions of Agapanthus were transfigured by its reflection in water.

Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Sylvia Slifka in memory of Joseph Slifka (527.1992)

Claude Monet (French, 1840–1926), Agapanthus, between 1914 and 1926. Oil on canvas. 198.2 x 178.4 cm (6' 6 in. x 70 ¼ in.)

Agapanthus at the Gardner

Gardner Museum horticulturists cultivate two varieties of the beloved lily of the Nile. They have been in our living collection for decades. Both are evergreen cultivars of Agapanthus praecox, the smaller of which is a periwinkle-colored dwarf hybrid known as ‘Peter Pan.’ Protected from the cold of New England’s winters, Agapanthus thrives pot-bound under glass in the greenhouses of our South Shore Nursery.

Photo: Jenny Pore

Summer Blues display in the Courtyard of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2022

Midsummer in the Courtyard of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, the wands of Agapanthus arch in toward the sunlight that streams through the atrium. The religious antiquities in the cloisters surrounding the Summer Blues display echo the flower’s symbolism of the divine. Further exploration of the Museum reveals floral imagery around each corner in every medium. Isabella’s passion for life speaks through her collection of art and the frame she created to share it with us.