Anna Coleman Ladd (1878–1939) is one of the few women artists whose work is included in the collection of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Gardner and Ladd were friends; there are several letters from Gardner in Ladd’s papers at the Archives of American Art and ten letters from the artist to Gardner in the Museum archives.

Anna Coleman Ladd, 1919

American National Red Cross photograph collection, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017669385/

Ladd’s bust of Maria de Acosta Sargent takes pride of place in the Macknight Room. The bronze bust, which Isabella purchased directly from the artist in 1915, shows de Acosta Sargent in a state of partial undress—a somewhat scandalous composition for a portrait at the time. With exposed shoulders and decolletage, her arms wrapped around her chest hold only the slightest hint of a piece of fabric.

Anna Coleman Ladd (American, 1878–1939), Maria de Acosta Sargent, 1915

Isabella flanked the sculpture with three works by John Singer Sargent, two watercolors and a charcoal drawing. The placement clearly celebrates Ladd’s accomplishment; Sargent was one of Gardner’s favorite artists and close friends and placing an artwork next to his would have been a high compliment. The choice may also have been motivated by the fact that the sitter was apparently a distant relation of the painter.

The sculpture of Maria de Acosta Sargent installed on the bookcase in the Macknight Room

Photo: Sean Dungan

A Philadelphia native, she studied sculpture in Europe and then moved to Boston after marrying Dr. Maynard Ladd. Both before and after her marriage, Ladd continued to achieve professional success abroad and at home. One of her most famous sculptures, the Triton Babies Fountain, is still installed in the Boston Public Garden. However, not long after Isabella purchased this bronze, Ladd’s career took a dramatic turn towards public service.

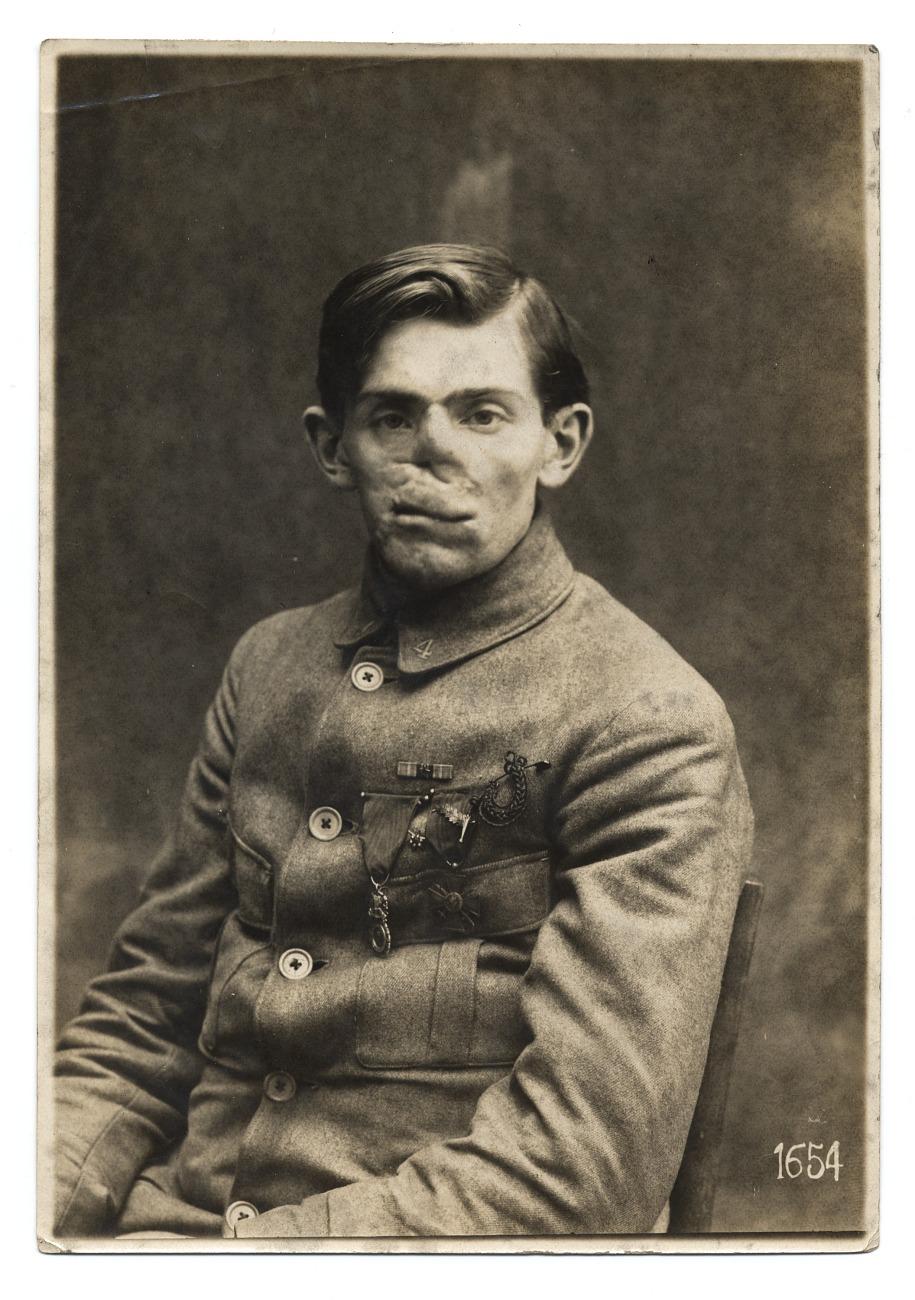

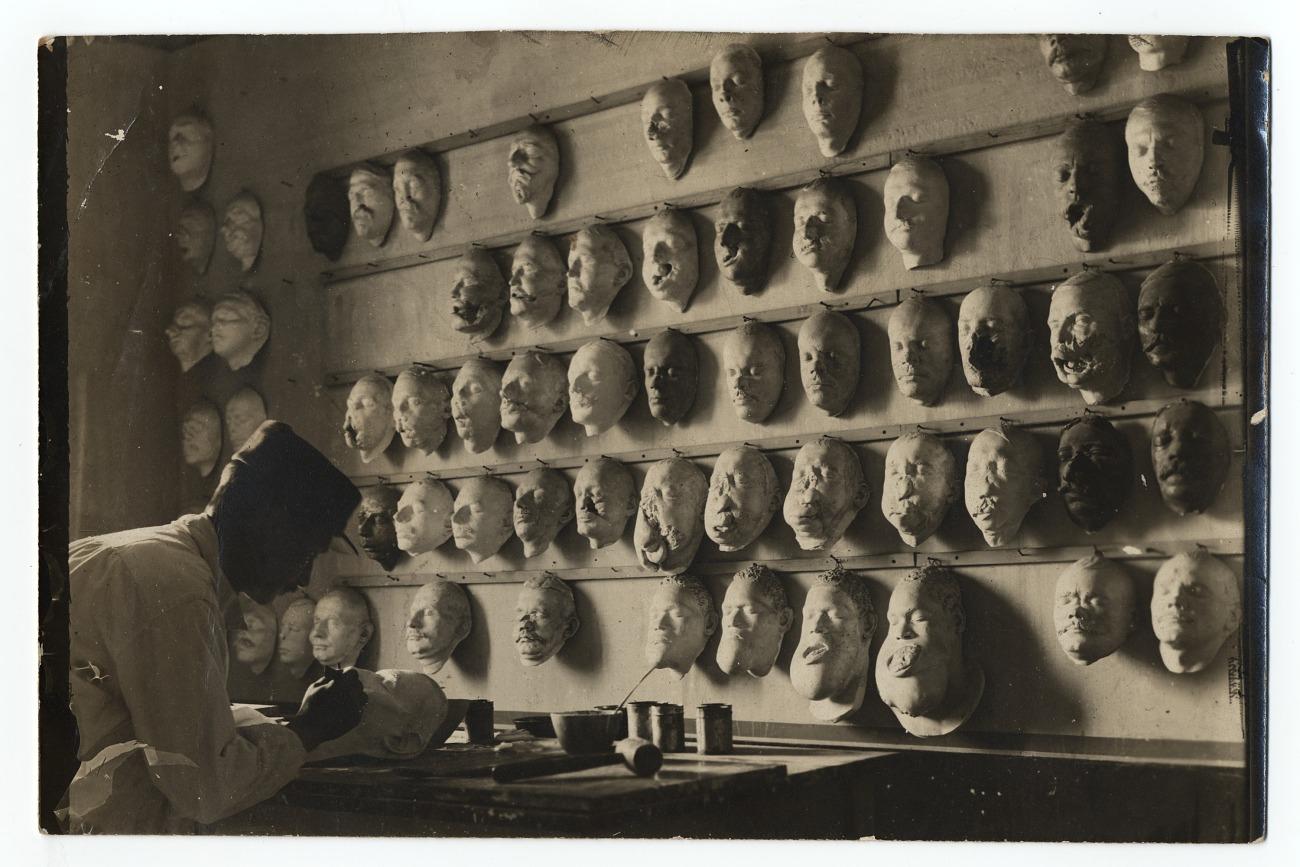

In 1917, during World War I, Ladd traveled to France with the American Red Cross. Turning her artistic talents to a patriotic use, she established a prosthetics workshop and used her skills to create custom sculpted masks for soldiers with severe facial injuries. The combination of the growing use of artillery in World War I—along with better battlefield medical care that allowed more soldiers to survive traumatic injury—left many veterans with lasting wounds and disabilities. Of the more than 600,000 French soldiers who were permanently disabled as a result of the conflict as many as 2,000 were because of facial wounds. Reconstruction with the nascent techniques of plastic surgery was rarely a viable option and these men consequently suffered from social stigma and severe depression.* This is where Ladd and her Paris studio—the American Red Cross Studio for Portrait Masks for Mutilated Soldiers—could help.

World War I soldier facial reconstruction documentation photograph, about 1918

Anna Coleman Ladd papers, 1881–1950. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Based on methods recently pioneered by English artist Francis Derwent Wood with British soldiers, Ladd and her assistants would carefully study photographs of a soldier before his injuries. Then, over a series of sessions with the veteran, they would create a facial prosthetic for him. These customized “life masks” made of copper covered the injury and imparted the individual with renewed confidence. Hand-sculpted and painted, they were matched not only to the soldier’s pre-war appearance but also to his skin color, so at first glance it was unclear he was wearing a prosthetic at all.

Of course, from a contemporary perspective, this attempt to mask facial injuries can come across as ableist or abusive by forcing soldiers who had been injured for their country to hide the scars of their service. However, at the time, Ladd and her colleagues—and apparently the soldiers they served—viewed it as the best possible option. The men claimed it helped them avoid what they called the “Medusa Effect,” meaning that anyone who saw their disfigured faces froze and stared.†

Ladd ran the workshop in France for eleven months and worked fervently to create ninety-seven facial prosthetics. When she returned to Boston, she wrote to her friend Isabella—who had, herself, helped pay for ambulance services in France during World War I—about her decision to put her fine arts on hold in order to make prosthetics. She begins the letter:

I want to see you, I know that you have been ill; but I also know that you are more wonderful than before. As for me, I am quite "unsuccessful"…I have done better work than ever in my life before...absolutely uncompromising sculpture, as I saw it; the search for beauty and austerity of line…expressing a need of the soul; or its combats; and the love of youth, in all its forms--youth, which has been nearly swept away in the late hellish upheaval.

— Anna Coleman Ladd to Isabella Stewart Gardner, 8 July 1920

This last statement—that the youth had been “swept away in the late hellish upheaval”—is particularly poignant. It alludes to the horrible violence and death wrought by the war. The names of the men who received prosthetics are largely lost to history, with an occasional last name written on an archival photograph or captured in not-yet-digitized Red Cross records. Their faces have been recorded only through images dedicated to documenting their injuries and how an artist was able to help them literally mask their scars.

Ladd’s part of this story is uplifting. It is, however, most important—especially on Veterans Day—to consider and commemorate the sacrifices the soldiers she worked with and many other men and women have made for their countries.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

*See David Lubin, "Masks, Mutilation, and Modernity: Anna Coleman Ladd and the First World War." Archives of American Art Journal 47, no. 3/4 (2008): 4-15. He also describes how the former soldiers often became reclusive as a result of their highly visible injuries.

† Lubin, 11